Passion for porcelain spanned the globe

By Sheila Melvin (The New York Times) Updated: 2012-09-16 09:42

|

Major works of porcelain are on exhibit in Beijing through January 6. A goose-shaped tureen from the Qing dynasty. Trustees of the British Museum |

|

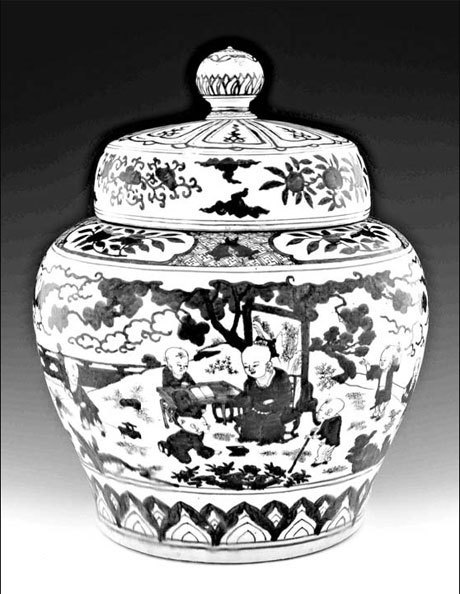

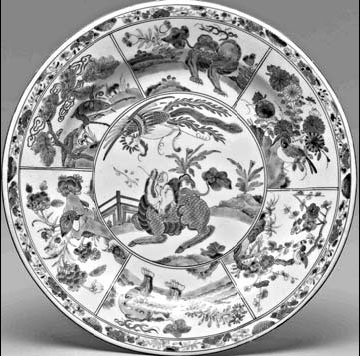

A jar from the Ming dynasty is decorated with boys playing; and a plate featuring panels of landscape and monsters, below. Photographs by Trustees of the British Museum |

Beijing

Wahen the National Museum of China and the British Museum decided to collaborate on an exhibition here that would celebrate two important 2012 events - the London Olympics and the Chinese museum's centennial - they chose to focus on something that played a vital role in the fortunes of both nations: porcelain.

"China is incredibly proud that they found the technology to make porcelain," said Jan Stuart, head of the Asia department at the British Museum. "They wanted to highlight that for the international and local audience."

It was potters of the Song dynasty (960-1279) at Jingdezhen who discovered the secret of porcelain production when they added kaolin to the China stone used to make other ceramics and raised kiln temperatures to above 1,300 Celsius. The resulting material was strong, translucent and brilliant white, allowing for the production of elaborate vessels that had unparalleled potential for decoration, and for which there was unprecedented demand.

"Porcelain really was the first global good," Ms. Stuart said. "It was crated all over, part of the modern economy and the silver trade."

Porcelain made a spectacular impact nearly everywhere it went, its ethereal beauty and startling strength leading some to ascribe magical powers to it. In one Southeast Asian culture, it was thought to be the progeny of shooting stars; in others it was said to heal the sick and call down spirits.

The Middle East - which had its own sophisticated ceramics tradition - had long been the biggest overseas market for Song ceramics. It quickly took to porcelain, and the Chinese Muslim merchants who managed this seaborne "ceramics route" introduced the Middle Eastern cobalt that enabled the creation of Ming China's signature blue and white porcelain.

As demand boomed, Jingdezhen's workshops grew increasingly specialized - each porcelain piece passed through the hands of roughly 70 craftsmen, with some workers just painting blue rims on bowls.

At least one porcelain piece had reached Europe by 1300 but significant exports did not begin until the late 1500s, when first Portuguese and then Dutch and English traders began shipping it - often as ballast on boats full of tea and silk - and ignited the "passion for porcelain," which has given the current show its name.

The exhibition, which runs until January 6, was also curated by the Victoria & Albert Museum, the first time these major institutions have jointly displayed their Chinese porcelain collections.

The first part of the show is devoted to Ming and Qing export ceramics. While most were blue and white, decorated according to Chinese taste, some were special commissions for wealthy Europeans.

One of the oldest is a blue and white serving dish (1520-30) made for a Portuguese customer that is decorated with peonies and the letters "IHS."

The monogram - a Latin abbreviation for Iesus hominum salvator (Jesus, savior of mankind) - is associated with the Jesuits, but the plate pre-dates their arrival in China, and even the founding of their order in 1534.

Other special pieces have less sacred origins, like the beer tankard depicting ships and a Swedish flag commissioned by a Swedish sailor marooned off Hainan Island in the winter of 1785; the punch bowl, from the same year, painted with a scene of a naval battle from the American Revolutionary War; the colorful dish (c. 1745-50) featuring Don Quixote and Sancho Panza; and the blue and white, double-necked oil and vinegar cruet (c.1690-1700) with silver mounts added in Europe.

These pieces all demonstrate the fascinating cultural exchanges that took place through the porcelain, as design concepts, decorative motifs and color combinations were drawn from numerous media - including architecture, painting, textiles and literature - in diverse cultures and then taken to China, reinterpreted and sent back out.

Demand for porcelain increased as dietary habits changed with expanding global trade and New World colonization. Costly beverages like tea, coffee and chocolate seemed to demand fancy dishes.

Likewise, as once hard-to-obtain spices became commonplace, the elite used elaborate porcelain dinnerware services to distinguish themselves from the riffraff. Bedazzled by the glories of porcelain, Europeans began to obsess over the secret of its manufacture.

"Porcelain was called 'white gold,' " Ms. Stuart said. But nobody knew how it was made. "It took a long time to find out what minerals were needed in what proportion."

The task of discovering this was largely financed by princes and delegated to alchemists, who were sometimes locked away in castles to pursue their task. One such unfortunate was Johann Friedrich Bottger, who had fled the Prussian court around 1700 after failing to turn base metals into gold only to be captured by Augustus the Strong - the porcelain-mad elector of Saxony and king of Poland - and forced to seek the secret of porcelain in a Dresden dungeon.

Bottger was given extensive resources - the historian Robert Finlay writes that his lab "was arguably the first research-and-development enterprise in history" - and he succeeded, in part by building on the work of his predecessor, E.W. von Tschirnhaus.

Augustus the Strong thus opened Europe's first porcelain works at Meissen in 1710, under Bottger's direction. He guarded against industrial espionage, even imprisoning his own employees, but the secret got out and porcelain was soon being made all over Europe.

The second portion of the exhibition features European porcelain and includes an early product of Meissen, an impurely white bottle adorned with cherub reliefs dating to 1715-1720. The production process improved quickly and soon the Europeans were making richly adorned, sculptural, often whimsical porcelain wares. Some were wholly original and some borrowed from Chinese designs.

Eventually, Jingdezhen craftsmen themselves began making pieces inspired by European porcelains.

The exhibition includes a number of intriguing pairings that show the flow of influence and inspiration between China and Europe, like two statues of the Daoist immortal Lu Dongbin, one made at Jingdezhen and one at Bristol, both dating to the mid-1700s. Another pairs a gold-striped ewer modeled after an ancient Greek wine jar and made at Derby (1780-3) with one made at Jingdezhen in the same neo-classical style, painted with scenes of the Derbyshire countryside (c.1785).

The last section of the exhibition is dedicated to ancient Chinese porcelain collected by Europeans. While some collectors bought in bulk and used porcelain to decorate virtually everything -mbedding it in walls and chimneys and even building "porcelain palaces" - others adopted a more considered approach and built priceless collections.

But Chinese collectors never took the same fancy to British porcelain, or to any other European manufactures.

Instead, silver flooded out of United Kingdom coffers to buy the tea and porcelain coveted by increasing numbers of British citizens - until British traders stanched the torrent by shipping opium to China, an egregious trade tactic that ended in war.

"Passion for Porcelain" records the positive side of these cultural exchanges.

"I want people to understand how important China has been for fueling the imagination of Westerners, but also to see some of the distinctive styles of the West," Ms. Stuart said. "This is a chance for people in China to see how something they first started took on a life of its own."

The New York Times

- 'Cooperation is complementary'

- Worldwide manhunt nets 50th fugitive

- China-Japan meet seeks cooperation

- Agency ensuring natural gas supply

- Global manhunt sees China catch its 50th fugitive

- Call for 'Red Boat Spirit' a noble goal, official says

- China 'open to world' of foreign talent

- Free trade studies agreed on as Li meets with Canadian PM Trudeau

- Emojis on austerity rules from top anti-graft authority go viral

- Xi: All aboard internet express