The emperor's noodles

|

|

Aozao noodles were one of Emperor Qianlong's favorites. |

|

|

Squirrel fish is named for its resemblance to a squirrel's tail after it's sliced and deep-fried. |

Suzhou cuisine has thrived on legends, history and natural flavors. Ye Jun finds out why it's still so popular today.

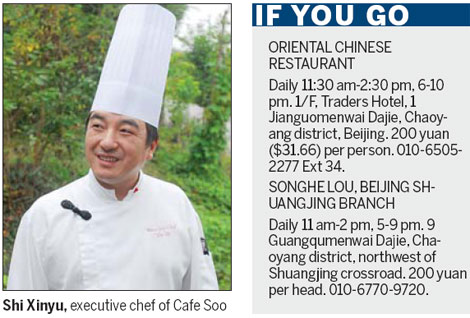

The cook was apologizing for the messy state of her kitchen, but she was misunderstood because her Beijing visitors did not understand the local dialect. That is why one of Emperor Qianlong's favorite noodles from Suzhou is known as "aozao", or "dirty", noodles. As the story goes, Qianlong was on one of his visits to the region when he got hungry and stopped by a village house in Kunshan for a meal. The old woman made him a bowl of noodles from her well-used stove, and the emperor enjoyed it so much he wanted to know its name. Beijing gourmets got a chance to sample these famous noodles recently when Shi Xinyu, executive chef of Cafe Soo at the Shangri-La Hotel Suzhou, Jiangsu province, came for two weeks to promote this famous dish. According to the T-Bazaar Restaurant at Traders Hotel Beijing, almost 1,000 bowls of noodles were sold in the 12 days the chef was here.

Shi says he had to import the noodles in from Suzhou because he could not find the right type in Beijing.

"Beijingers generally like their noodles rather soft. But people in Suzhou prefer their noodles to have some texture," he explains. The Suzhou noodles are thinner and drier than those available in Beijing.

Chef Shi brings the noodles to boiling point twice so they still have a little bite in the center. Then he drops them into a bowl of broth. The broth itself is a careful preparation made from slow-boiling pork bones, an old hen, grass carp, eel bones and river snails. He also adds a secret selection of Chinese herbs.

The noodles are served with a slice of braised pork belly, a slice of spiced duck, and a chunk of deep-fried grass carp with sauce. The pork belly is braised for four hours, and cooled for another two hours before it is sliced, a process that makes it particularly flavorful and smooth.

It sounds very complicated, but that's how precise Suzhou cuisine can be in its preparation. It is part of the regional Huaiyang cuisine, recognized as one of eight major Chinese cuisines.

Suzhou is not just a popular tourist destination but also a traditional gourmet capital. Most people in China know the city as "heaven on earth", along with its sister city Hangzhou, capital of Zhejiang province.

It is known for its colorful silk, elaborate and elegant landscaped gardens, and flowing rivers and arched bridges that crisscross the city. The network of canals has won Suzhou the sobriquet "Venice of the East".

The city's growth into a gourmets' paradise was very much due to its strategic location along the Grand Canal that connected Beijing to Hangzhou.

It was the main transport artery at the time, and it helped make Suzhou a commercial hub in East China, especially during the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911).

Chef Shi grew up along Qili Shantang, a popular tourist destination that combined picturesque river scenes and shopping on ancient cobbled streets.

"In Suzhou, some dishes are made to taste light and original, while some are prepared with dense oil and red sauce in contrast, depending on the different ingredients," Shi says.

For example, Suzhou people simply saute tender slices of bamboo shoot with shepherd's purse. But they also make yanduxian, a soup that cooks bamboo shoot, with both fresh and salted pork slices. Local restaurants are known for the flavorful spiced duck and jiangfang, or squares of pork belly braised with red sauce.

Yellow rice wine, famous in the area, is often used to marinate and braise meat, giving the dishes a special aroma.

It would be too simplistic to categorize Suzhou cuisine as just "light" or "sweet". While some northerners think Suzhou cooking tends to be too sweet, Shi says sugar is used just to lift the freshness in dishes, while salt is still the main seasoning.

Food critics say Huaiyang cuisine represents the future of Chinese cuisine because of its clever use of fresh ingredients, natural flavors and wide range of cooking methods.

Judging from the many visitors who flock to Songhe Lou, an old Suzhou restaurant in an equally old street in the center of the city, it may not be a far-fetched expectation.

Here the signature dishes includes squirrel fish, a mandarin fish expertly sliced and deep-fried so it bristles like a squirrel's tail. It is both a visual winner and a culinary favorite for its sweet-and-sour flavors.

And, like any restaurant worth its salt, it also has a Qianlong anecdote. The emperor, it seems, fell in love with the squirrel fish as soon as he tasted it.

Then, there is the restaurant's cherry pork, so named because the sauce is cherry red and very aromatic from the red yeast used as seasoning, and also because the meat is cut into cherry-sized portions.

Fish and shrimp are favorite ingredients in Suzhou, mainly because of its proximity to the water. It's natural then that the city's most famous dishes include prawns stir-fried with a famous local green tea called "biluochun" or "emerald spring spirals".

There are seasonal delicacies like knife fish, which swim against the currents of the Yangtze near Suzhou to reach the upstream stretches where they spawn. They are considered best just before Qingming - the Tomb Sweeping Festival - which falls around the first week of April every year. They are considered rare delicacies and cost a fortune at Huaiyang restaurants.

At a time when fusion has become a trend, very few Chinese restaurants serve dishes from just one cuisine. Such dishes as quick-fried shrimp, pork meatballs with crab roe and crabmeat, and steamed pork with ground rice in lotus leaf are all available in many Chinese restaurants.

Suzhou cuisine is also absorbing popular elements from other cuisines, says Li Fending, Huaiyang cuisine chef with The Oriental Chinese Restaurant at Traders Hotel Beijing.

"Many restaurants in Suzhou still retain traditional dishes," Li says. "But if you keep everything the same all the time, you'll soon be left behind."

Li's own restaurant serves both Cantonese and Huaiyang cuisines.

Shi says Suzhou cuisine depends so much on the chef's skill and inspiration that it cannot develop as fast as Cantonese cuisine.

"Some techniques are already lost because they were too complicated," Shi says.