Do Chinese mainland insurers really possess that 'value investor'DNA?

Updated: 2016-08-17 07:19

By Luo weiteng in Hong Kong(HK Edition)

|

|||||||||

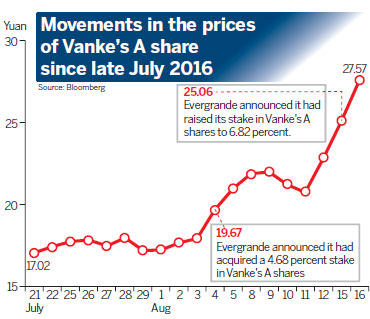

The high-profile takeover battle between Chinese mainland homes builder China Vanke and the once-obscure property and insurance conglomerate Baoneng Group stands as the poster child of mainland insurers snapping up stakes in listed companies since last year.

Despite Vanke Chairman Wang Shi's calling Baoneng's buying spree an act of "barbarians at the gates", a debate over the landmark corporate tussle has revolved around whether it has highlighted how investment-hungry insurers stand at the frontier of value investing in the mainland's highly speculative stock markets.

Their aggressive strategies, as some suggested, may shake up underperforming companies and encourage investors to take a hard look at corporate fundamentals. At the same time, it also mirrors a dearth of investment channels in the country that, basically, makes insurers place big bets on stock markets for higher yields.

Last year, a cluster of mainland insurers, including Anbang Insurance and Foresea Life Insurance, a little-known unit of Baoneng, spent more than 1.1 trillion yuan ($16.6 billion) on 31 stake purchases to amass 6.79 billion shares of some 35 domestic-listed companies, with a clear appetite for large blue-chip stocks in the real estate and banking sectors, according to Shanghai-based financial data firm Wind Information. It indicates insurance capital's liking for value stocks that have long been underpriced.

The mainland's once high-flying stock markets, where more than 90 percent of over 200 million trading accounts are owned by retail traders, are nothing less than a casino with investors trading fast and speculating mainly on rapidly soaring stocks.

With the country's stock markets still licking the wounds of last summer's rout, Baoneng's bold move points to a long-awaited value discovery story that mainland capital markets are desperately calling for, says Jacob Zhou, a consultant at one of the "Big Four" accounting firms.

As the mainland's largest property developer by sales, Vanke has long seen its share price in the past eight years hover at half the level of its all-time high in 2007.

Baoneng's stock purchase, starting from late last year, stands as a much-needed boost, not only in driving Vanke's share price all the way up back to its historic highs at one time, but also in giving a big push for undervalued blue-chips in glamour-free sectors - from home appliances to food and beverage - that have long waited for the market to appreciate them, Zhou says.

More importantly, with the protracted share purchase grabbing headlines for more than eight months, the market is looking at whether value investing, something that's common in the West but hardly practiced on the mainland, would come back into focus.

"Basically, the bargain-hunting insurers are becoming a force at a time when a floundering domestic economy cries out for a healthier and professionally dominated financial market," says Fielding Chen Shiyuan, Hong Kong-based Asia economist at Bloomberg Intelligence.

China's growing middle class, currently estimated at one quarter of a billion strong, is the catalyst for the already-thriving insurance business.

The booming demand pointed to insurers' asset allocation, which is now confined to a lack of investible financial assets originating from the sustained imbalance between the high savings rate of mainland households, low-yielding fixed income products squeezed by low interest rates and weakening fundraising demand from a flagging real economy, says Ouyang Hui, a distinguished chair professor of finance at the Cheung Kong Graduate School of Business in Beijing.

|

The high-profile takeover battle for China Vanke, as well as the surge in Vanke's share price, may have drawn investors' attention to "value investment" - a theory that's common in the West but hardly practiced on the Chinese mainland. Provided To China Daily |

According to the China Insurance Regulatory Commission, the average returns on stocks from 2004 through 2015 reached up to 12.5 percent, dwarfing the 4.41 percent of bonds and 4.37 percent of bank deposits, and making equities the highest-yielding investment option for insurance capital.

However, the post-disaster stock market was cited as the major drag for mainland insurers' shrinking profits in the first half of this year.

Large blue-chips with sustained robust sales and profits, therefore, would continue to be popular targets, underpinning insurers' proactive strategies of value investing amid the gloom and doom of financial markets, Chen reckons.

Yet, such an optimistic tone isn't shared by everyone.

"Basically, one can never make me believe that Baoneng's share acquisition is a much-awaited story of value investing," said an analyst who wished to remain anonymous. "With financial headwinds continuing to weigh on the yields of alternative assets, the investment frenzy from the likes of Baoneng for listed companies is the mere result of having no other option."

Insurers like Baoneng, he pointed out, come without a track record of long-term investments in the property and banking sectors. The nature of financial institutions as such determines they typically put money on short-term thinking to win the day. When financial markets turn around, they would be well-expected to dump stocks immediately to make the quick buck, said the analyst, who sees Baoneng more of a "spoiler". As a vegetable wholesaler-turned-insurance, finance and property conglomerate, Baoneng just doesn't have the "value investor" DNA, he observed.

Even putting the "value investor or not" argument aside, acquisitive insurers have also raised concern over how their buying spree would undermine the long-term health of their balance sheets.

Unlisted and small and medium-sized insurers, in particular, which cannot benefit from economies of scale, tend to offer high-risk, high-return products in an asset-driven manner to mitigate pressures from insurance proceeds, says Ouyang.

Certainly, their purchases are mainly funded through the high-risk, high-yielding "universal life" products - the top-selling life insurance policies combining death benefits and an investment element.

By the end of last year, total premiums of universal life products on the mainland amounted to more than 600 billion yuan.

Some 650 universal life accounts from 52 mainland insurers now provide returns ranging from 4 to 8 percent, compared with the average returns of 4 percent offered by their listed counterparts.

For one thing, with the issuance of high-return products, such insurers are forced to place more bets on stock markets in a bid to foot the bill and guard against policy surrender. For another, their aggressive investments need to be funded by offering of more universal life products, says Ouyang. At the heart of the mounting fears is insurers' investments being exposed to highly volatile stock markets, underlining the uncertainties of cash flows that insurance firms are required to set for liabilities stretching into the future.

Such a liquidity risk not only comes from insurers' stockholdings in listed companies, but also from sectors they invest in and the whole stock markets, says Li Xinyu, a professor of the Department of Risk Management and Insurance at Peking University.

Li believes that insurers' stock purchases, typically, are a good thing - they ring alarm bells for companies whose management hasn't done much work to repay shareholders and boost the depressed share prices. Also, the purchases inject fresh blood into the country's lackluster stock markets and serve as a "booster shot" for the fragile investor sentiment.

However, being a stable rather than a momentum institutional investor doesn't necessarily ask insurers to buy a controlling stake in listed companies and directly get involved in the corporate management, Li says.

More focus should be put on playing a better role of a "financer" rather than a "professional manager", which may make insurers' acquisitions much more "welcomed", she adds.

As regulators have tightened their grip by reducing the total premiums allowed to be invested in high-risk products and asking insurers to make clear the source of insurance capital used for share purchases, Ouyang believes the issue still goes back to the much-discussed capital market reforms.

According to Ouyang, the industry today only has four listed insurance companies, with a crowd of unlisted, small and medium-sized insurers denied the access to fundraising in the primary market.

Even in the secondary market, they are beset with obstacles. The accumulated balance of corporate bonds, for instance, constitutes no more than 40 percent of an insurer's net asset.

"Insurance companies are still waiting for the market reforms to smooth the way for diversifying their asset portfolios. And, we will wait and see whether insurers would become part and parcel of the trend of value investing," says Ouyang.

sophia@chinadailyhk.com

(HK Edition 08/17/2016 page1)