-

News >Bizchina

Taking China's risks seriously

2011-02-15 13:46

A static watch gives the right time twice a day. But it is of no use for the rest of the time. This fact is worth keeping in mind when looking at China's economy this year. For much of the last decade some people have predicted imminent doom and gloom for China. But their predictions are like reading the time by a static watch.

China has continued to grow from strength to strength. Its economy has soared. Its influence has grown. And all this has benefited Asia as well as the rest of the world.

The question then is: Is 2011 the year when problems in China will emerge? Is this the time when the static watch is right?

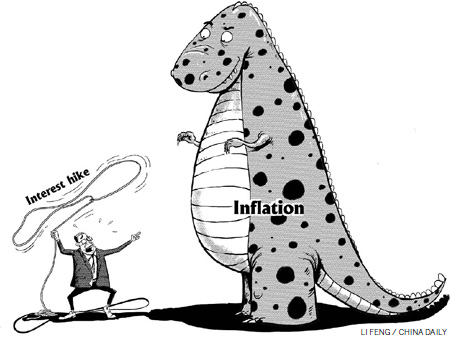

China's risks are different from those of the West, where debt problems persist. Across Asia, inflationary pressures are rising and monetary policy needs to be tightened.

The challenge for China is that in recent years it has tied itself too closely to the United States' monetary policy. In doing so, it has kept interest rates lower than necessary and its currency weak. Resolving these issues is vital and China has already started doing that.

The US and China both need to set monetary and fiscal policies to suit their domestic needs. The US is doing this. Facing deflation, the Federal Reserve (Fed) introduced a second round of quantitative easing, or QE2, last year despite the criticism it evoked from other countries. The US administration has followed it up with a huge fiscal boost. The expected result: The US economy will grow strongly this year, particularly in the first half.

Although the stimulus has reignited fears over the US government's debt, the reality is that the US had no choice. A staggering 43 million Americans get food stamps today, a clear indication of the scale of poverty. It is possible that the US policy will work in terms of ensuring growth, if not in solving all the problems of the country.

All of this highlights the need for Asian policymakers to follow the US - not by copying US policy, but by setting monetary policy to suit their domestic needs. The challenge is especially daunting for China.

The longer it takes China to tighten its policy, the greater its eventual problem. The Chinese authorities imposed a loan quota last year. But concerns over growth prevented them from making the quota tight enough. This year, however, there is no reason to hold back because growth looks set to be strong, boosted by the 12th Five-Year Plan (2011-2015).

China's policy tools, no doubt, worked well during the financial global crisis, but there are risks now.

First, it has become harder to control the size of China's still fast-growing economy and its private sector.

Second, there is a need to rebalance the economy from investment to consumption. And although investment always sounds good, it is now so high in relation to GDP that not all of it may be worthwhile.

Third, China's vulnerability arises from its underdeveloped financial sector. Despite rising incomes, the options for investing household savings are limited: low interest-bearing bank accounts; equities, where governance concerns persist; or real estate where prices are already sky-high. This makes the economy prone to bubbles.

China needs to avoid the lethal combination of cheap money, one-way expectations and leverage. A few years ago the talk in the US was about the "Greenspan put": Interest rates kept low to support the equity market. China can't fall into the same trap with its property market.

All this raises the risk of a near-term setback in China. Rising food prices and wages add to the sense of urgency.

The authorities do not want to derail the economy. But any setback that makes growth suffer will have global ramifications, hitting commodities and trade, among others. Of course, if growth suffers a setback, the static watch doomsayers will claim they were right and there would probably be much speculation over the existence of bubble in China's economy. That would be wrong.Any slowdown in growth would probably be temporary - a strong sign that the business cycle exists in China. Besides, while the economic trend is up, there will be setbacks on the way.

These factors will provide a buying opportunity, not a reason to doubt the economy's rise. China's growth is for real. It is not a bubble economy. It is an economy prone to bubbles. And there is a big difference between the two.

In recent years, markets have discounted the bad news in the US and finally taken seriously the flaws in the eurozone. The near-term risks facing China, like many countries in Asia, need to be taken seriously. Yet they also need to be kept in context, because they are unlikely to alter the longer-term positive outlook for growth.

According to Standard Chartered Bank, the world economy is in a super-cycle: a sustained period of high economic growth lasting a generation or more. The global economy is twice the size it was a decade ago and has already reached above its pre-recession peak.

A central feature of this super-cycle is the shift in the balance of economic and financial power from the West to the East, led by China. This was highlighted at the recent summit between President Hu Jintao and US President Barack Obama in Washington.

Soon after becoming president, Obama changed the relationship with China. Under his predecessor, George W. Bush, the US had a Strategic Economic Dialogue with China. Obama turned it into a Strategic and Economic Dialogue. This was significant. It emphasized the twin aspects of the relationship. But because the US recovery has been disappointing, the focus has been less on the "strategic" and more on the "economic" dimension of their relationship. Although the US has a larger economy, the relationship increasingly resembles one of equals.

The economic importance of China for the world economy has not been greater in modern times. It is vital for the world, Asia and China that Beijing addresses its inflation challenges now. This is no time to wait.

The author is chief economist and group head of global research at Standard Chartered Bank.