No longer going by the book

|

|

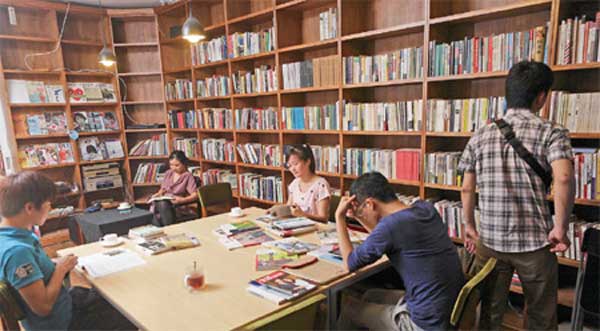

Facing increasing competition from online sellers, traditional bookstores are trying to provide diversified services to win over customers. Provided to China Daily |

Traditional bookstores are thinking outside of the box to remain viable

The ending has been written for Borders Group, the second-largest bookstore chain in the United States. The big-box retailer has started liquidating its 399 stores after a failed attempt to find a buyer during its bankruptcy process.

Borders' failure tolls the bell of caution for bookstores all around the world.

Influenced by the popularity of online stores and e-readers, bookstores could go the way of record stores, as many have closed or are still struggling to survive.

The book business is still profitable as annual retail sales for Chinese bookstores pull in more than 70 billion yuan (7.55 billion euros), according to Xinhua Bookstore Association Director Zhang Yashan. But there are a variety of factors plaguing storefronts.

Besides the hit from online companies, the huge increase in rent for commercial property is another reason freestanding bookstores are closing. One Beijing bookstore owner has experienced a rate of rent increase of 15 percent every year.

With no pressure to pay rent, online bookstores can provide customers discounts. Dangdang.com, China's biggest online bookstore, slashed its prices by 35 percent in April and by 50 percent in May as a way to attract more customers. Other online bookstores, such as 360buy.com, are taking part in the price war.

Another way to encourage more business is to not charge for shipping costs. According to Zhang, the market share of online bookstores increases every year. In 2009, it was about 10 percent, and gained 3 percentage points in 2010.

Zhang says that at present there are about 140,000 to 150,000 bookstores in China, among which there are 14,000 State-owned Xinhua Bookstores.

Zhang says that 20 to 30 percent of independent bookstores have closed in recent years. Without financial support from the government, he says they can't afford the rising cost of rent and employees' salaries.

"The State-owned bookstores have an advantage compared to privately owned independent bookstores. The storefronts belong to the bookstores and they do not have the pressure of paying rent," Zhang says.

But they have something in common with independent bookstores: fewer customers.

"To survive this crisis, the business pattern for both State-owned and independent bookstores must change," Zhang says.

To continue operating, large and independent bookstores alike are transforming from traditional operating methods and are providing diversified services to attract more customers.

The Bookworm, an independent bookstore, has three stores in China located in Beijing, Chengdu and Suzhou.

The store in Beijing, which opened seven years ago, is located in the Sanlitun area and caters to expatriates. Many foreigner logophiles consider it a favorite place to hang out.

The sign outside - "Eating, Drinking and Reading" - promotes more than just a bookstore. For Jeffery Rambo, from California, The Bookworm is a community resource for him.

"Many social events are held here and I can meet many people and make friends with them," Rambo says.

But as an English teacher, he is also drawn to the literature, and typically visits The Bookworm at least once, sometimes twice a week.

"Staying here and having some quiet reading time is a big enjoyment for me. I like tangible and traditional books," Rambo says.

Xiamen-based Chinese bookstore chain Apodon has adapted its business platform to draw younger customers. Apodon was founded eight years ago and is a privately owned bookstore.

Apodon Public Relations Manager Yu Zhenghui says that to be a successful bookstore, businesses have to provide readers a special space to relax, something online bookstores cannot achieve.

"There are more than 20 Apodon bookstores in China and most are located in big cities, such as Beijing and Shanghai. Young people with huge life and work pressures love a quiet place where they can forget their worries," Yu says.

A typical Apodon bookstore, instead of only selling books, provides comfortable sofas, offers coffee, free Wi-Fi and sells other products such as stationery.

Yu says Apodon wants to create an image of cultural connotation that can arouse people's sense of belonging.

Yu claims that Apodon doesn't want to be just a bookstore, but a cultural products provider. Which is why he doesn't consider online bookstores as an opponent.

"Online bookstores and Apodon are not in competition because our services are different, though our target customers are the same group, young people living in big cities," Yu says.

Compared to bookstores, customers can sometimes get discounts online and don't have to leave the comforts of their home.

"I think online bookstores and real bookstores can co-exist because we satisfy different requirement of our customers," Yu says.

Zhou Hezhu is the owner of a little bookstore that opened in 2002 located near the University of International Business and Economics in Beijing.

"In the past three years, because the popularity of online bookstores, we have lost some of our customers," Zhou says.

To cope with the decrease of customers, Zhou has changed the types of books he is offering.

"I have made a clear focus for my bookstore since my target customers are university students. So the center of our business has changed to selling textbooks," Zhou says.

Zhou says a bookstore has to create its own characteristics and then it can gain popularity from a specific group of readers.

Rebecca Wood, who is from California but lives in Beijing, is a director of academics and advanced studies in an international education agency and also an avid reader. She says she prefers actual stores to online bookstores.

"I think real book lovers will choose to buy books in actual bookstores," Wood says.