Banking on change

|

|

Leading economist says china must transform its growth model soon

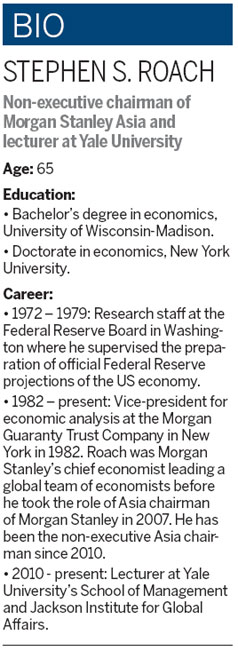

Stephen Roach, one of the most prominent economists on Asia, is used to swimming against the tides of conventional wisdom.

He was among the earliest voices on Wall Street to predict, in early 2001, that the United States economy was facing a long stretch of weak growth. During the 1997 Asian financial crisis, when most critics expected China to be one of many Asian countries to fall hard, Roach, who was then Morgan Stanley's chief economist, said China was not going to fall. He was right.

Now, however, Roach is singing the praises of China's economy to a more common tune: The economy must change its growth model - now.

At his Yale University office in New Haven, Conn, Roach says China must move increasingly away from its exports- and fixed-investment-driven economy of the past 30 years toward growth that is propelled mainly by Chinese consumers. He points out that he has repeatedly made this point in the last few years, after Premier Wen Jiabao gave a speech in early 2007 in which he said China's economy, although on the surface appears to be strong, is unsustainable.

"Wen Jiabao was the first to raise the alarm. He was saying that China was growing at a spectacular rate but it can't stay this course if we don't deal with our imbalances. He lays out a whole framework that has enabled us to understand where China is going next," Roach says. "Now the financial crisis gives (China) a reason to change the model. I think they (the Chinese leaders) get it," Roach says.

|

He wrote a piece called This China is Different in the Financial Times in the 1990s that opened the door for him in China. He was later introduced to prominent senior Chinese leaders, including former Premier Zhu Rongji.

About a decade later, Roach gave up his position as head of a highly regarded team of economists to become chairman of Morgan Stanley's Asia operations in Hong Kong, becoming the first economist to land such a senior position with the bank.

Roach's decision to become chairman of the bank's Asia operations did not come easily, he recently said. When John Mack, then chairman of the board at Morgan Stanley, offered him the position, Roach was reluctant to take it because he wanted to stay in his position as chief economist for the rest of his career. But after realizing that the Asia operations might be an exciting way for him to broaden his perspective on a region that was fast becoming very important to him, he took the job. During his three years in Asia, he wrote a collection of essays about China's growing stature in the world economy that was published in his book The Next Asia.

Last fall, Roach returned to the US to take up a teaching position at Yale University while juggling his time as a non-executive chairman of Asia for Morgan Stanley in New York City. He will be teaching four courses this fall: "The Next China", "Lessons on Japan", "Wall Street and Washington", and "Macro Debate", in which he will debate macro issues with a leading macro theorist at Yale for 25 lectures.

Roach is widely recognized as one of Wall Street's most influential economists, but anyone meeting him for the first time would be surprised by his down-to-earth manner. For someone who possesses more than 30 years of experience as an economist in the US and Asia, he certainly does not try to appear larger than life.

As the non-executive Asia chairman (which means he is no longer based full-time in Asia), Roach flies regularly to Asia for meetings with clients and government officials in the region.

Roach says his teaching position gives him the opportunity to clear up "a lot of misperceptions" that Americans have about China.

"I truly feel that Americans lack a basic understanding of what's been going on in Asia, whether it's problems in Japan or the development miracle in China. And what worries me a lot over the past five to six years is an outbreak of protectionist sentiment directed at China," Roach says.

A prolific speaker, Roach has given numerous testimonies before the US Congress over the years about US-China trade tension.

"I think one of the biggest misperceptions is that Washington and American workers don't understand the context of our trade balances with China. It is driven by a shortfall of American savings," Roach says.

After studying China's economy for more than a decade, Roach says he is most impressed by what the Chinese have accomplished in 32 years. Calling it the "China Miracle", he credits the Chinese economic success to four factors: strategy, commitment, strong tools to implement strategy and a focus on stability.

"During the Asian crisis, China was building currency reserves and current accounts surplus. They did not go to the IMF. They did not devalue their currency. And they were very, very focused on building the greatest export machine the world has ever seen," Roach says.

The US economy, on the other hand, is a completely different picture. Recovery will be slow and weak in the next three years and there's no ruling out the possibility of a double dip recession, he says.

"In a scenario where we go back to recession, we don't have good policies to deal with it. If you have a zero interest rate, you don't have a lot of tools," he says.

Roach is much more optimistic about China's future, especially if more consumer spending occurs.

If China transforms to a more consumer-oriented economy, it will likely spark the greatest consumption story in modern history and that will have profound implications for China, Asia and the growth-constrained economies of the European Union and the US.

But in shifting to a more consumption-led model, Roach says, China will reduce its savings and have less left over to fund ongoing deficits of countries like the US. The possibility of such an asymmetrical global rebalancing - with China taking the lead and the developed world dragging its feet - would be the key unintended consequence of China's new model, Roach says.

"So if the world's biggest surplus saver is going to adjust, but the world's biggest spender is not, then it is perfectly reasonable to ask the question: Who's going to fund America's savings or current account deficits?"