Guess work

|

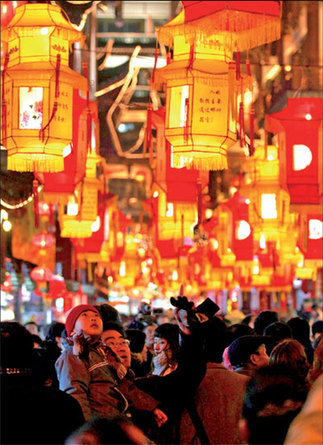

The tradition of lantern riddles dates back hundreds of years. Zhang Jian / For China Daily |

Ancient Chinese word game infused with essence of culture continues to delight in modern times

In a small conference room in a building in Beijing, dozens of slips of paper in various colors, each adorned with one, two or three Chinese characters, hang on the walls. About 20 people, most of them graying and wrinkled, are packed into the room.

Most of the time there is dead silence in the room as those in it look at the slips of paper, deep in thought. Now and then there is an eruption of laughter and a sage nodding of heads as someone comes up with a winner, or an outburst of argument as the members quibble over something that some feel has missed the mark.

We are at a gathering of the Beijing Riddle Fans' Association in the Cultural Center of Dongcheng district, which meets on the last Sunday of every month. Each member brings at least 10 "lantern riddles" they make for others to solve, says Zhao Chunlin, president of the association.

The pastime of lantern riddles dates back hundreds of years and invites participants to draw on their imagination using Chinese characters and sometimes drawings, which are attached to lanterns. The participants are required to find answers to posers that can be as obscure and as devilishly difficult as The Times crossword.

"Making and solving lantern riddles is funny and enriches the mind," says Lu Cuiping, 43, a nurse.

Lanterns and riddles are two aspects of Chinese culture, and they were not combined until the Southern Song Dynasty (1127-1279), says Wang Qian, 66, a lantern riddle aficionado.

In the ancient capital of Hangzhou, in eastern China, a lantern festival that fell on the 15th of the first lunar month provided a forum to show off their talents and knowledge. Scholars would past or hang riddles on the fancy silk lanterns to challenge the passers-by. Those who were fast of wit were rewarded with writing brushes, paper and the like.

The riddles satirized or ridiculed social events, with humorous pictures of people, and hidden meanings and obscure words.

|

"Appreciating beautiful lanterns of various colors and shapes is a great joy, and solving riddles is challenging and funny," Wang says. "When lanterns and riddles are combined, their charms are hard to resist."

Solving lantern riddles soon became popular public entertainment, not only during the Lantern Festival, but also for some other traditional holidays such as Spring Festival and the Mid-Autumn Festival.

"At temple fairs, luxuriant business streets and in the courtyards of rich families, people of all ages rush for the fun and challenge of solving lantern riddles," Wang says.

Lantern riddles were also used as romantic matchmakers. "Riddle makers wouldn't say exactly what they thought; instead they expected like-minded people to find the answers," Wang says.

"So during festivals people used lantern riddles to find partners whose thoughts were similar."

Players can be divided into two factions: those who prefer the cerebral, with strict rules and whose subjects, such as ancient sayings and old dynasties, are more refined; and those who prefer lantern riddles lite, a watered down version with few rules in which the subjects can be many and varied.

Enchanted by the wisdom of the riddles and the fun of solving them, lantern riddles became a popular pastime among scholars. They set up small groups and met regularly to discuss the riddles, Wang says.

Scholars who went to the capital for the imperial examinations would also spend their spare time playing lantern riddles. "They would pose riddles and ask the others to solve them. It was also a way for them to pit their wits against one another," Wang says.

Eventually, during the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), the scholars drew up rules for the game. There was much more to the game, it seemed, than a question, an answer and a lamp.

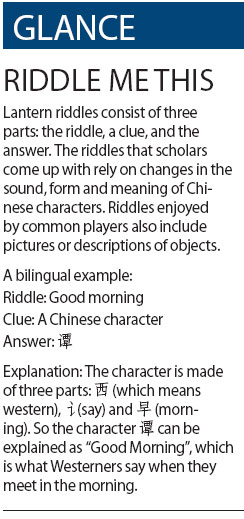

"The subjects of their riddles were mainly poems or verses from ancient classic books," Wang says. "Their fun drew on changes in pronunciation, form and meaning of Chinese characters. For them a good riddle needed three things: the same characters could not appear in both the riddle and its answer; the riddles had to be funny and elegant; and the riddle itself had to be a complete word, phrase or a sentence."

Solving lantern riddles made by scholars usually required a highly erudite mind - only those well versed in poetry and books were allowed to take part, with the reckoning being that only they could appreciate the riddles' sophisticated charm. With the game restricted to an elite few, ordinary folk could but watch and listen.

However, this did not curb the enthusiasm of the less learned for the game, and they hung lantern riddles whose subject matter was the trappings of everyday life, such as kites and firecrackers. Those riddles lacked the elegance of the riddles spun by the elite, Wang says.

The development of lantern riddles reached its peak in the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911), when emperors, chancellors, scholars and ordinary folk were all great fans. At that time the subjects of the riddles covered almost every part of daily life, Zhao Chunlin says.

It was also common for chancellors to use riddles to get in a dig at, and even mock, the emperor. One tale has it that during the Qing Dynasty a chancellor named Ji Xiaolan asked the emperor to solve a riddle whose subject was 皇帝的脚 (The emperor's feet). The clue was: a Chinese character.

The emperor racked his brain without success. Ji Xiaolan then gave him the answer: 蹄 (hoof or hoofs).

"蹄 is made up of 足 (feet) and 蹄 (emperor), which is quite logical," Zhao says. "So even though the emperor was furious, there was little he could do or say."

Nowadays, solving lantern riddles is still a popular activity in festival periods. Riddle subjects can include books, songs, TV series and travel.

"I get my inspiration for lantern riddles from everyday life, and it relies on acquired knowledge," Zhao says. "To make good riddles you have to learn and to never stop thinking."

Solving lantern riddles is also a traditional activity at parties. Zu Zhenkou, who used to work in embassies in New Zealand, Liberia and Sri Lanka, says solving lantern riddles was a must at parties attended by Chinese living in those far-flung parts.

"Lantern riddles are not only replete with wisdom; they carry the essence of the culture. Solving the riddles connects you with China."

Gao Yushun, 66, an English teacher, has used Chinese lantern riddles in his classes, drawing on their playfulness to engender students' enthusiasm for their new language.

"Solving lantern riddles is a teaching method for me, and the students really enjoy it."