Artist imagines mission to Mars

|

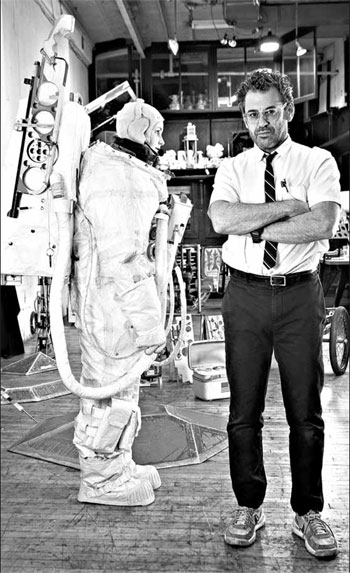

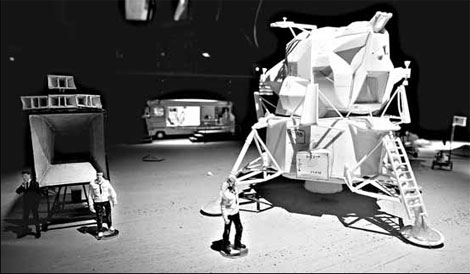

The artistic side of a space mission is being energetically explored in a studio in Manhattan. The artist, Tom Sachs, with a suited-up assistant; a detail of a model of Mr. Sachs's coming installation, top. Photographs by Natan Dvir for The New York Times |

In his studio in Manhattan, Tom Sachs has been planning obsessively for a manned mission to Mars.

But Mr. Sachs is an artist, and his space journey will go only as far up as the Upper East Side.

The air its astronauts breathe will be of a late springtime New York City composition. The landing module from which its astronauts emerge will be made mostly from plywood and screws. And the surface their motorized rover explores will consist not of rocky red soil but of the flat century-old pine boards that form the immense, 5,100-square-meter drill floor of the Park Avenue Armory at East 66th Street.

Since the Armory's transformation in 2006 into one of the largest contemporary-art exhibition spaces in the country, artists have approached the drill floor's 55,000 square feet with widely varied modes of assault. It has been draped with Lycra tulle (Ernesto Neto), "painted" with the aid of peeling-out motorcycles (Aaron Young), and turned into an oddly didactic Renaissance painting classroom by the director Peter Greenaway, whose installation looked lost in the setting.

|

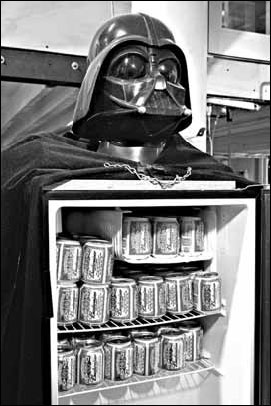

Darth Vader chills the beer. |

For a month beginning May 20, Mr. Sachs will become the latest artist to take on the daunting space, where he will display all manner of objects, some quite realistic - the rover, the lander (a life-size model of the real Apollo lunar lander), a mission control center, a mobile quarantine unit - and many others, like a boombox outfitted with solar panels and a beer fridge shaped like Darth Vader. But his larger intention is to transform the drill hall into a theater for an extended piece of performance art, one that mines the United States space program for an entire prefabricated aesthetic - script, choreography, costumes, sets - and also for a complex load of cultural baggage about what fuels the compulsion to explore outer space.

Mr. Sachs, 45, has long had a reputation in the art world as a kind of high-comic tinkerer and provocateur who remakes industrial and consumer objects in an abject wood-shop fashion, as if to reclaim the mass-produced world for humanity or at least reopen humanity's eyes to the things that increasingly make up its visual landscape.

He has carried this objective to sometimes sensationalistic lengths. In 1999 the dealer Mary Boone was arrested after a Sachs show featuring handmade shotguns and an Alvar Aalto vase full of real bullets for people to take home.

At the Jewish Museum in 2002 he exhibited a scale model of a German concentration camp made from a Prada hatbox, an equation of fashion and fascism whose "irony, if that's what it was," Michael Kimmelman wrote in The New York Times, was lost on the Holocaust survivors who wrote him in angry disbelief.

Mr. Sachs's do-it-yourself aesthetic has always straddled the line between art and science project, and the critical knock on him has often been that he labors perhaps a little too much to satisfy his own material fetishes.

With "Space Program: Mars" the risk is that the project will be seen less as an art installation than as a monumental space-nerd amusement park, a view that Mr. Sachs said would greatly underestimate his ambitions.

"I always feel that people really misunderstand my vision, especially when it comes to NASA," he said.

His fascination with the space program goes back many years - he staged a mission to the Moon at Gagosian Gallery in Los Angeles in 2007 - but it did not grow out of boyhood astronaut fantasies. It grew instead out of his conviction that the Apollo program, one of the crowning technological achievements of the 20th century, was in itself mostly a work of performance art, one that spoke volumes about America's aspirations and fears.

Relative to their immense cost the Moon shots produced little of practical value, their real goal being cold-war cultural and political spectacle, which placed them, Mr. Sachs said, firmly in the realm "of the useless and spiritual, just like art." He saw it all as a perfect kind of ready-made. And like many artists of his post-post-Duchampian generation he set out to remake it in his own style, not casually but by adopting all the discipline and can-do spirit that President John F. Kennedy summoned in his famous 1962 Moon speech.

"I'm a complete perfectionist, as you can see, in my own filthy way," said Mr. Sachs one morning in early spring in his studio.

"I like to say that unlike the military, where you have to build something to such an exacting degree that it works every time and doesn't kill someone, we have to build it so that it will work at least once," he said. "But that's still very hard to do, and we're very serious about it."

He even sought the advice of real space scientists, befriending engineers at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory near Pasadena, California, two of whom came to New York to visit his studio in 2010 and have acted as unofficial advisers ever since.

"It was going to be just a lunch meeting," said Adam Steltzner, one of the engineers, "and it actually ended at 3:30 or 4 in the morning the next day. It was kind of unbelievable. It was a very high-level interaction."

Sitting one morning in the rover, parked surreally in an old oak-paneled storage room at the armory awaiting its mission, Mr. Sachs said, "There's a very fine line between having great knowledge of all these scientific and technological and industrial cultures and actually becoming a part of them."

Whether he still knows the location of that line may be an open question. "We're really going to Mars," he said with a smile radiating Chuck Yeager confidence. "I mean, we're doing it here at the armory, but except for the setting, we're really going."

The New York Times