Do coffee, do good

|

Sahra Malik (right) focuses on the marketing of the company's sustainable products, while her sister Alia promotes corporate social responsibility, Photos by Feng Yongbin / China Daily |

Three siblings are among the first to sell locally sourced, organic, fair-trade, and sustainably grown coffee, among other goods, from Yunnan farmers. They tell Emily Cheng their story over a cuppa.

The Chinese population currently consumes less than five cups of coffee per capita per year. In the United States the figure is a little more than 400 cups. In Japan it's around 300.

Breaking into the coffee market in China - a market dominated by tea - is not an easy feat.

But as the middle class in China continues to grow, so too has the trend of embracing new food and beverages, as well as healthy and socially responsible lifestyles.

Three years ago, a trio of native New York siblings anticipated this trend and set up a forward-looking coffee company, Shangrila Farms.

Sahra, Alia and Safi Malik were among the first to sell locally sourced, organic, fair-trade, and sustainably grown goods. Shangrila Farms is a social enterprise that offers coffee, honey, and skin-care products sourced directly from Yunnan.

"A social enterprise is different from a normal business as part of the founding principles have to do with not just profits," says Alia, 30. "Its purpose and mission has social and/or environmental objectives also."

Last year's drought highlighted the need for a controlled water source independent of shifting rain patterns. It prompted the trio to embark on a coffee farm irrigation project. If successful, it will reduce water usage and provide a safeguard for the quality of the coffee and offer stability for the farmers' livelihoods.

A lot of consideration is given into ensuring that everybody wins. "Everyone needs to make some profits along the way. That gets tricky: How do you price it so you remain competitive in the market? Customers are still quite price-sensitive, especially if you're a new brand," says Sahra, 31.

The inspiration for the company came after befriending local coffee farmers during annual trips to Yunnan, where their Pakistani father and American mother own a house.

The family first came to China in 2003, after the father was assigned as the head of the United Nations Development Program in China. Their mother founded an NGO based in Yunnan.

The cooperative of coffee farmers that they encountered had strong beliefs about high quality and natural products, but they were particularly poor compared to others selling cheaper, lower-quality beans. The farmers were trained by foreign experts in the 1980s but were left without the skills necessary for marketing their superior products.

Seeing the potential unrealized by the farmers, Sahra quit her position as senior art director at Dell to help increase their distribution.

"I really felt like I wanted to put my creative skills to something more. The end result is not to get rich; it is to help people," she says.

Sahra used her design skills to create more marketable packaging for the coffee. Safi, 24, jumped on board and applied his university-acquired business skills to help launch the business. By coincidence, Alia, who has a background in development, was simultaneously building her own line of natural products.

It was only after a year that the trio realized they were working on similar projects. Getting together "just made a lot of sense," Safi says.

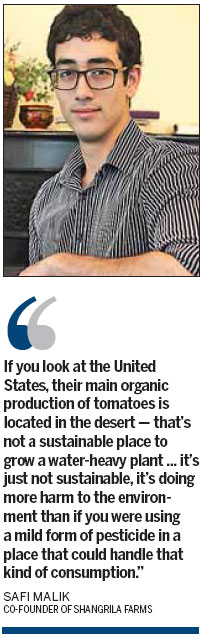

At their headquarters in Beijing, Sahra focuses on the marketing, Alia works on corporate social responsibility, while Safi manages general business operations.

The trio has created a sustainable business model by consolidating the coffee production into a regionally specific process: The beans are grown, roasted and packaged locally.

When you buy roasted coffee from the farmers, Sahra says, "it gives them another source of income, whereas green beans are a commodity. You only earn so much money from selling green beans. It's actually a rare thing for the beans to be roasted locally."

Most pre-packaged roasted coffee in China changes hands seven times before it reaches the store, she says. Shangrila Farms' coffee travels from farmer to consumer via just three parties and gets to Beijing within three days.

The farmers they work with have a cooperative of plantations in ecological protection zones. The area has no other industry for 20 kilometers and the local government enforces green farming.

"We don't require the farmers to be certified as organic because it's difficult and expensive for them," Sahra says.

Safi says that being certified as organic should not be the sole focus.

"If you look at the United States, their main organic production of tomatoes is located in the desert - that's not a sustainable place to grow a water-heavy plant. It's considered organic because there's no pesticides or fertilizer but at the same time it's just not sustainable, it's doing more harm to the environment than if you were using a mild form of pesticide in a place that could handle that kind of consumption," he says.

While organic certification has value, Safi and his sisters say more attention should be paid to sustainability and fair-trade practices.

"Since the Sichuan earthquake there's been a huge surge in social consciousness in China" Alia says. "We have lots of applications from young people who want to work for NGOs or with something that is more meaningful to them. I think China is evolving in that regard."

Contact the writer at sundayed@chinadaily.com.cn.