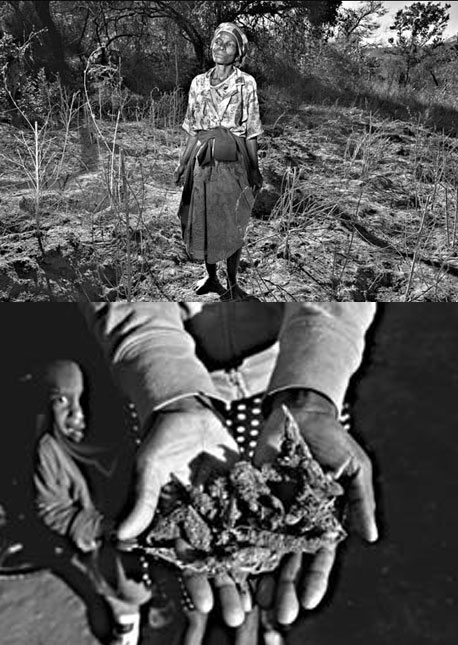

Poor grandmothers grow marijuana

|

|

PIGGS PEAK, Swaziland - After her daughters died, Khathazile took in her 11 orphaned grandchildren. It is what a gogo, or grandmother, does in a country where the world's highest H.I.V. infection rate has left a sea of motherless children.

Khathazile is relying on Swazi Gold, a highly potent strain of marijuana that is sought after in the thriving drug market of next-door South Africa. Deep in the forest, atop a distant hill in this arid corner of tiny Swaziland, she grows Swazi Gold to keep her growing brood of grandchildren fed, clothed and in school.

"Without weed, we would be starving," explained Khathazile, who asked that only her middle name be used.

Khathazile is one of thousands of peasants eking out a living in the rural areas by growing marijuana, according to relief workers, embracing it as a much-needed income boost that is relatively hardy and easy to grow.

Khathazile says she started growing it when her attempts at other crops failed. "If you grow corn or cabbages, the baboons steal them," she said.

In Swaziland, Africa's last absolute monarchy, deep poverty remains the rule here in the rural hinterlands around Piggs Peak, in the country's mountainous northwest. Not much grows in its rocky soil, and jobs are scarce. Many young people flee to Swaziland's cities or to neighboring South Africa to look for work.

That leaves behind a lot of old women and children. An aggressive rollout of antiretroviral therapy has helped curb the country's AIDS death rate, but the disease has hollowed out virtually every family in one way or another, leaving older siblings caring for younger ones and frail grandparents struggling to raise small children once again.

It is the story of Khathazile's family. Since 2007, her three daughters have died, leaving a total of 11 children. She moved them into her one-room hut.

"I cannot abandon these kids," Khathazile said.

There is a market for families' alternative source of income. According to the United Nations, South Africa has reported rising marijuana use. Swaziland, a tiny nation of about 1.4 million, was reported to have more area under marijuana cultivation in 2010 than India, a nation more than 180 times its geographic size.

The grandmothers of Piggs Peak must find a secret field to plant, often one deep in the forest, which they reach by walking for hours. Clearing a patch is tough work. They have to buy seeds, if they are new at planting, as well as manure. The police often search for marijuana fields just before the harvest, and burn them to the ground.

A good harvest can yield as much as 11 kilograms of marijuana. But they sell to middlemen who come through the villages at harvest time, and have little bargaining power. Most make less than $400 per crop.

"The men come from South Africa to buy, but they cheat us," said Sibongile Nkosi, 70. "What can we do? If you sit with it the police can come and arrest you."

Ms. Nkosi said she started growing marijuana even before her daughter died and left her with two orphans to feed.

Enterprising growers bury part of their harvest in watertight barrels deep in the woods, saving them until December when the supply dries up and prices rise. But most of the grandmothers need the money immediately, not six months from now.

"When you are in poverty, you must do whatever you can to live," Ms. Nkosi said.

The New York Times