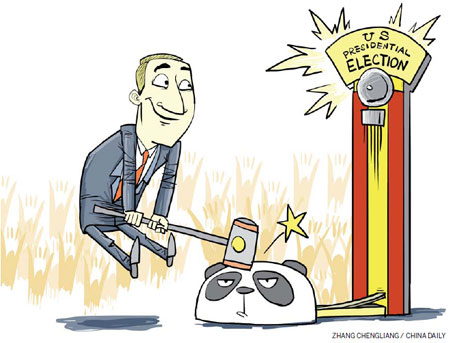

China's role on US political chessboard

Ultimately, the two presidential candidates know how valuable a piece it is

The recent announcement by the Barack Obama administration that it was filing another case against China at the World Trade Organization just before the president visited Ohio, a key election battleground state, highlights how important China has become in the US political process. China has been an issue in US presidential campaigns since president Richard Nixon's historic visit in 1972. It has been a major issue since 1990, when the candidate Bill Clinton heavily criticized president George H. W. Bush for being soft on China, despite the incumbent's strong rhetoric and the imposition of four trade cases affecting nearly $4 billion in trade.

In today's economy, US presidential candidates must respond to the discontent of blue-collar workers who have seen their jobs displaced overseas and to the broader and growing anxiety about the world's second-largest economy.

Candidates at all levels must take a position on China. Many voters have a deep sense that China is not competing fairly, even if they do not understand precisely how, and that China is benefiting at the expense of the US economy and jobs. A recent poll by the Pew Research Center found that 46 percent of the US believes China has overtaken the US as the world's leading super power or soon will. Voters expect candidates, especially for president, to be forceful advocates for the US.

In a news conference Obama said: "China has been very aggressive in gaming the trading system to its advantage and to the disadvantage of other countries, particularly the United States. Currency manipulation is one example of it." He supported the first safeguard case (tires) sent to him by the US International Trade Commission. (George W. Bush rejected four cases). Obama's administration has taken a strong stand against China in trade matters, actively filing cases at the WTO, including cases on rare earths, raw materials, electronic payment systems, poultry processing, and most recently duties on US-made automobile parts. Strong enforcement action is important politically to show manufacturing workers that Obama is as tough on China as Mitt Romney, his Republican rival, would be.

Despite Obama's strong words and assertive actions, Romney challenges Obama for being too soft on China. He decries China's "preponderant power" and the "accelerated military build-up". He advocates stronger relationships with Asian partners with whom "we share a concern about China's growing power and increasing assertiveness" and "closing off China's option of expanding its influence through coercion".

Fortunately, the protectionist rhetoric is more reflective of political maneuvering than of either candidate's policy. The outcome of the election will affect the relationship between the US and China only modestly and only at the margin. The fundamental relationship, already strong from 30 years of working together, will continue to be productive and with growing cooperation regardless of who wins. The Strategic and Economic Dialogue and the Joint Committee on Commerce and Trade are proceeding with constructive discussions on important issues for both countries.

However, at the margin and especially in the beginning of a new term, a Romney administration is likely to present a more contentious relationship. Romney has promised to label China a currency manipulator on his first day (technically, a label assigned by the new treasury secretary).

The implications of the label are unclear. No actions are required by the US government except for more discussions and no automatic restrictions on private-sector activities. Attaching the label currency manipulator could be a politically aggressive but commercially mild event.

A more accurate predictor of post-election policy is the agenda of US business. Business people have a comprehensive agenda, including a bilateral investment treaty, government procurement, sensible export control reforms, rule-making transparency, harmonizing standards, barriers to financial services, and much more. The prospects for economic growth from deeper economic integration will be the driving force in US policy toward China.

A second Obama term or a Romney administration will bring cooperative economic diplomacy. Both the US and China have a strong interest in defending and advancing the rules and norms of the international economic system that have benefited both of them enormously. Either president will also continue rigorous enforcement of anti-dumping and anti-subsidies laws, with a dose of WTO dispute cases. The list of claimed barriers to US exports into China set out in the National Trade Estimate is long, and Congress expects action on them.

One probable difference might come in the last two years of the next administration. It is normal for presidents finishing a second term, the last years of an eight-year administration, to focus on a legacy of global leadership and strong relations with major US strategic and economic partners. History suggests that a re-elected Obama would take a less aggressive enforcement position toward China early in his second term and would focus much more actively on building the relationship for the final two years.

On the other hand, experience suggests that if Romney were elected he would live up to his campaign promises by taking an aggressive enforcement position toward major trading partners, probably with a quick symbolic action against China. But, like Obama, he would soon focus on building the relationship.

However, if Romney ran for re-election, China would inevitably be a big campaign issue, and he would be criticized for being soft on China. He would have to spend the second half of his first term proving his toughness. As a result, US statecraft toward China for 2015 and 2016 would include more rhetorical confrontation.

It is important to know that despite the heated campaign rhetoric this year and probably again in 2016, the fundamental relationship between the US and China will continue to be built on commercial opportunity, economic growth and the critical strategic bond that must grow between the two largest economies. Leaders in both nations understand the global importance of this relationship. It is inconceivable that they will not step up to these vital responsibilities.

The author is professor of trade and development, Monterey Institute for International Studies; adjunct professor, Georgetown University. The views do not necessarily reflect those of China Daily.