Storm relief exposes New York's deep divides

|

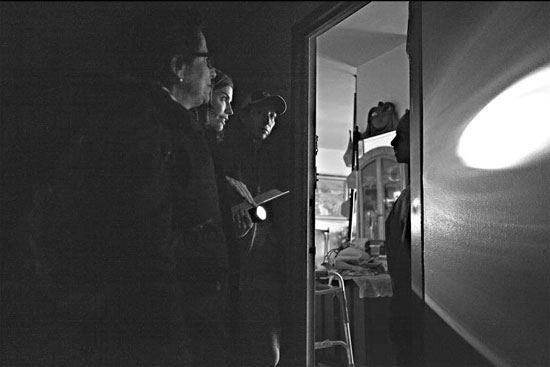

Volunteers stirred resentment after Hurricane Sandy. An offer of food and water at a New York housing complex. Members of the Occupy Wall Street movement ran a storm center in the Queens section of the city, below. Nicole Bengiveno / The New York Times |

After more than a week of self-sufficiency, George Ossy, an immigrant from Africa living amid the chaos of the Rockaways, with his 10-year-old daughter in tow, walked into the relief center set up down the street by the volunteers who had descended on the storm-battered peninsula in the Queens section of New York.

Moments later, a white woman leaned down to address his daughter. "Have you eaten in two days?" she asked.

Mr. Ossy, a taxi driver, surged with outrage, insulted by the suggestion that his daughter was not well cared for.

"I said: 'What do you think? You think we live in the bush?'" He felt condescended to by the volunteers - many of them from upscale neighborhoods in Manhattan and Brooklyn. He turned and left.

Hurricane Sandy separated New Yorkers with power and heat and the many other assurances of modern life, and those without. But the storm simply made plain the dividing lines in a city long fractured by class, race, ethnicity, geography and culture. In reminding of these divides it like Red Hook, Brooklyn, suddenly found themselves inside them, trudging up pitch black stairwells to inquire about the well-being of the mostly poor black and Hispanic residents.

But even within the glow of unity that has come to follow tragedies here, these disparities can be difficult to ignore, occasionally provoking friction and misunderstanding.

More privileged New Yorkers unearth deep guilt among the piles of donated clothes as they come face to face with misery that existed so close to home even before the storm.

Those coming to them for relief worry that their helpers are taking some voyeuristic interest in their plight, treating it as an exotic weekend outing, "like we're in a zoo," said one resident of a Rockaway housing project.

While the good being done is undeniable, the gap-bridging atmosphere has a melancholy undertone for some who are sure the moment is fleeting.

From her Manhattan apartment, where she had been without power for several days, Kelly Warren, 48, and a friend lugged 500 pairs of new socks and underwear bought at Walmart to the Rockaways. "I'm driving in my big Lexus coming down here," Ms. Warren said, betraying her self-consciousness. "I said, 'Thank God the car is dirty.'"

A similar scene was unfolding in the shadow of the Red Hook Houses, a housing project with nearly 3,000 apartments. Stung not only by pervasive income inequality, but also by the steady march of gentrification in this once-derelict area, some here found it hard to accept aid from the same young people who were paying more to live here, pricing out longtime residents of the neighborhood.

But realizing that this demographic group, long held up as the villain in the tale of life in the projects, could care, was just as hard for some residents.

"They've been talking about white people as bad for so long, they feel shaky, embarrassed," Al Pagan, 46, said as he watched the volunteers help his neighbors. "They're starting to realize white people are human beings just like us."

The counterculture activists of the Occupy Wall Street movement found themselves tearing up sodden drywall in damaged houses owned by police officers, whom this time last year they despised only slightly less than the richest 1 percent. Upper East Side professionals headed into clapboard neighborhoods of Staten Island and got their hands dirty cleaning out basements. And white gentrifiers who may not have thought much about the brick public housing complexes scattered around trendy neighborhoods suddenly found themselves inside them.

Moments of understanding have emerged not only along lines of race, but also along the more elusive boundaries of class and culture. In the Rockaways, growing numbers of visitors have rankled locals in recent years.

As several young men from a Manhattan consulting firm, one wearing a Princeton University sweatshirt, tore up destroyed flooring, any tension seemed to have been dumped with the first wheelbarrow of drywall. The owner of the house said that the men's boss told him "he wanted them to see hardship, to get out and work with their hands, because they mostly went to Ivy League schools."

Some volunteers have entered the more fraught area of applying their own values to those they are helping.

As she gave out diapers and cases of infant formula, Bethany Yarrow, 41, a folk singer from Williamsburg who has been volunteering with other parents from the private school her children attend, said she was shocked by the many poor mothers in the Arverne section of the Rockaways who did not breast feed. The group, she said, was working on bringing in a lactation consultant. "So that it's not just 'Here are some diapers and then go back to your misery,'" she said.

That sort of response has rankled Nicole Rivera, 47, who lives in a project. "It's sad, sometimes it's a little degrading," she said.

Ms. Rivera said that she was thankful for the help, but that its face - mostly white, middle- and upper-class people - made her bitter.

"The only time you recognize us is when there's some disaster," she said. "Since this happened, it's: 'Let's help the black people. Let's run to their rescue.'"

"Why wait for tragedy?" she added. "People suffer every day with this." stirred a hope that they could be bridged.

The New York Times