Once-thriving Mayas struggle for survival

|

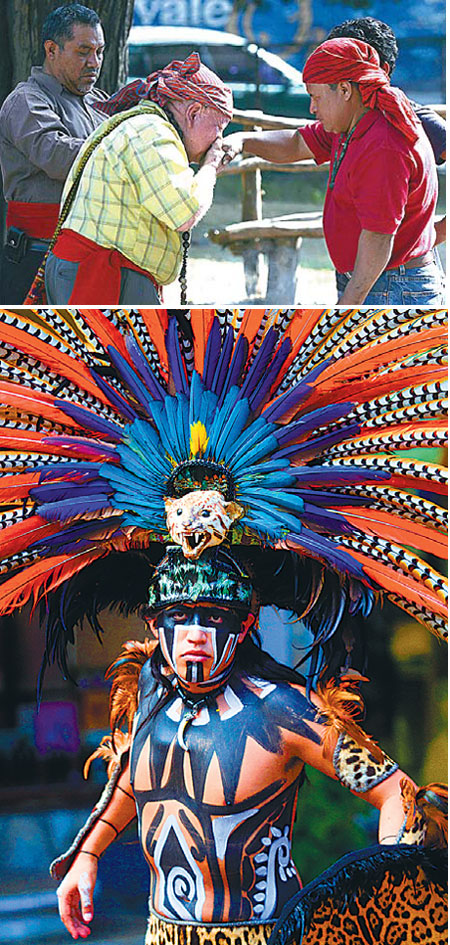

Top: Mayan shamans perform a purification ritual during celebrations for the upcoming end - Dec 21 - of the Maya cycle known as Bak'tun 13 and the start of the new Maya Era, at the Kaminal Juyu site in Guatemala City, on Tuesday. Johan Ordonez / Agence France-Presse Above: A Mexican man wearing a costume performs at a tourist area of Playa del Carmen in Mexico. Pedro Pardo / Agence France-Presse |

At its peak, the Mayan civilization had one of the richest cultures in the Americas. Today, ethnic Mayas in Central America and Mexico suffer from discrimination, exploitation and poverty.

In Guatemala, where nearly half of the population is indigenous descendants of the once-mighty ancient civilization have even fallen victim to genocide.

The rich Mayan culture will be in the global spotlight Friday when revelers - and doomsday watchers - will mark the end of a 5,200-year era as sketched out in the elaborate Mayan calendar. But the plight of indigenous Mayas in the region will likely go undiscussed.

"The indigenous population was always seen as cheap labor, and this persists to this day," said Guatemalan anthropologist Alvaro Pop, a member of the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues. "They are seen as a tool and are not the focus of public policies."

The Mayan civilization reached its peak between the years 250 and 900, but then slipped into decline around 1200. Three centuries later, during Spanish colonization, the Mayas were dispossessed of their lands and reduced to poverty and servitude.

Today, there are an estimated 20 million to 30 million direct descendants of the ancient civilization living in southern Mexico, Belize, Honduras, El Salvador and Guatemala, where the indigenous group is most prevalent.

In Guatemala, ethnic Mayas often find themselves on the margins of society, with limited access to education, healthcare and other basic services. Their native languages are not officially recognized.

Within the indigenous community, which accounts for 42 percent of Guatemala's 14.3-million-strong population, the poverty rate is 80 percent.

Nearly six in 10 indigenous children suffer from chronic malnutrition, and the infant mortality rate has hit an alarming rate of 40 per 1,000 live births, according to the United Nations Development Programme.

In Mexico's Chiapas state, social misery and exploitation led to the creation in 1994 of the media-savvy but later weakened Zapatista National Liberation Army, which drew attention to the community's plight.

But ethnic Mayas paid perhaps the heaviest price during Guatemala's civil war, which pitted the army against leftist guerrillas from 1960 to 1996.

"There were external reasons which exacerbated the population's poverty and led to a stigmatization of indigenous people," according to Pop, the anthropologist.

More than 600 massacres of indigenous communities were recorded during that period, and tens of thousands of Indians sought refuge in southern Mexico from the brutal counter-insurgency by the military, according to a 1999 UN report.

Under the scorched-earth policy conducted by the regime of then-dictator Efrain Rios Montt, who ruled in 1982 and 1983, entire villages were wiped out.

In the midst of this systematic repression, indigenous activist Rigoberta Menchu rose to prominence. Her strong condemnation of the massacres earned her the Nobel Peace Prize in 1992.

"The armed conflict was used as a pretext to exterminate the indigenous population, physically and spiritually," Menchu said.

Agence France-Presse