Micro blogs make graft fight hot news

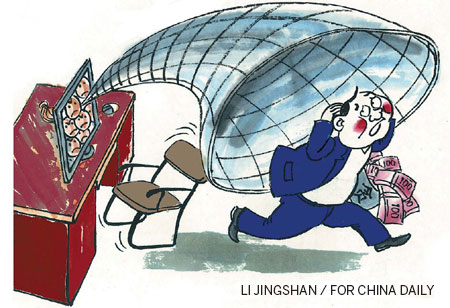

More people are using social media to tackle corrupt officials, as Cui Jia and Cao Yin report.

As one of the first people in China to attempt to expose corrupt officials via micro blogs, Zhou Wenbin considers himself the teacher of Luo Changping, a reporter who recently used his micro blog to accuse a ministry-level official of abuse of power.

Zhou, who works at Lixin county's land and resources bureau in Bozhou city, Anhui province, didn't realize the power of the micro blog until he decided to post news of his visit to the city's Commission for Discipline Inspection on April 13, 2011, where he planned to accuse his bureau chief of accepting bribes.

"I spent a year informing the county-level Commission for Discipline Inspection of my suspicions, but they just ignored me," Zhou, 45, said.

However, when he told a friend about his plan to take the issue to a higher authority, the friend suggested he use Sina Weibo, a micro blog service often known as "China's Twitter", to publicize the trip and generate greater public attention.

Zhou registered for a Sina Weibo account, and practiced making posts on his "not-so-smart mobile phone" for a week before he carried out his plan.

During Zhou's journey to Bozhou and roughly an hour after he sent his first post exposing his bureau chief, the City Commission for Discipline Inspection contacted him, as did a television station, which displayed great interest in reporting the story. "I didn't expect to get feedback that quickly. Many people used their micro blogs to express support for me, which made me feel I wasn't alone."

Under pressure from the public and the press, the commission dispatched a team to Lixin county to investigate the case three days after Zhou's visit. Zhou's claims were upheld and the bureau chief was warned and disciplined.

'Flies' and 'tigers'

"What I did was quite innovative back then, but now exposing officials on micro blogs has become an everyday occurrence because of the attention it generates, both from the public and the media," said Zhou, who recently bought a smartphone to enable him to update pictures and text more quickly.

"I only caught a 'fly', while Luo caught the first 'tiger' in the wake of a pledge by China's new leadership to fight corruption. We both have to thank the micro blogs," added Zhou.

In April, President Xi Jinping reaffirmed his Party Congress message that the disciplinary authorities must crack down on both "tigers" and "flies", referring to officials involved in major or minor corruption.

In December, Luo used his Sina Weibo account to publicly accuse Liu Tienan, director of the National Energy Administration and a deputy director of the National Development and Reform Commission, of falsifying his academic qualifications and engaging in "improper dealings" with business associates.

Luo said on Monday that it had taken him a year to confirm and crosscheck the tip-offs he'd received before posting them on his micro blog. In its initial response to Luo's accusations, the NEA press office denied the allegations, but it emerged that Liu was removed from his official posts on Tuesday.

Sina Weibo now has more than 368 million users, a huge jump from the 50 million registered users it had roughly three years ago. Although an increasing number of people regard social media, especially micro blogs, as an effective means of tackling corrupt officials, the official attitude to it is conservative and cautious.

"Exposing officials online is not an official way of reporting corruption," said Zhang Shaolong, an inspector from the petition office of the Commission for Discipline Inspection of the Central Committee of the CPC, during an online interview in May.

"The authorities investigated a number of officials after leads were provided on the Internet, but we have to admit that there are concerns about online tip-offs. Some of the information posted was false and some posts were simply a means of letting off steam and were very difficult to verify," he said. He urged people to report corrupt officials through the confidential, official channels, because he feared whistleblowers may be putting their lives at risk by making accusations on a public forum.

In April, a number of popular Chinese websites provided links to government departments' official anti-corruption websites, but experts said most people still prefer to use the unofficial channels because of the huge amount of public attention they receive.

Attracting attention

"Many of those who provide information about graft think that reporting it on official websites will not generate enough attention, compared with the Internet, which is why they prefer to publish on micro blogs, instead of informing the disciplinary departments directly," said Jiang Ming'an, a law professor at Peking University.

"It also highlights the negligent way in which the authorities sometimes deal with reports from the public," said Jiang, who has been invited to participate in a central government conference on anti-corruption work. He added that officials should be prepared to defend themselves if members of the public cast doubt on their probity.

Meanwhile, the disciplinary authorities must investigate information posted on social networking platforms and provide public feedback, he said. "If the information provided is false, the authorities must quickly make that clear. Not all online reports are 100-percent accurate and we need to protect innocent officials."

If there are no rules covering online allegations of corruption, especially on some micro-blogging platforms, the potential exists to damage the reputations of officials, infringe their privacy or even libel them, he said.

To avoid these problems, the government should formulate laws to regulate online allegations of corruption. The best way of doing that would be to write them into an anti-corruption law that many experts have been calling for over a long period. In addition, those who attack officials for reasons of personal malice will be forced to justify the false allegations if the case becomes the subject of an official investigation.

Luo Changping said the success of his complaint against Liu was an isolated event and doesn't mean that the system has improved.

Ren Jianming, director of the clean governance research and education center at Beihang University in Beijing, said social media is just one way of cracking down on graft and will not tackle the root cause of the problem.

"Online anti-corruption efforts will encourage more people to provide information, give their opinions and participate in supervision, but it's not a practical way of solving the problems caused by graft," he explained.

Some people believe they will not be punished if they forward untrue posts or even publish false information, because the authorities cannot determine the original source among the thousands of posters and forwarders, "but they can be charged with defamation or spreading false accusations, according to the current laws", he said.

Web companies and some local governments also have the power to establish "black lists" to warn those who repeatedly publish false information and possibly fine them, he added.

Zhou Shuzhen, a politics professor at Renmin University of China, agreed that social media can play a major role in cracking down on official corruption, but warned it can only reflect the tip of the iceberg.

"The online battle against graft must be better managed and guided or it will encourage false information and rumors," she said. "The platform can help the government search for, and collate, information, but sometimes there's a danger that the part may serve as the whole, but may not accurately reflect the whole truth."

In this way, the challenge of making better use of the Internet and social media is more important than the platform itself, she added.

One employee of a micro blog service provider, who declined to be named, said the company will not disclose user information to the authorities even if users publish false allegations. The disclosure of this information is prohibited by a clause in the service contract customers sign before opening their online accounts.

However, the intention of some people who make allegations, such as reporters, is to arouse the attention of the disciplinary authorities, and therefore they are actively encouraging the authorities to question them about their claims, according to the unnamed employee.

"In fact, Web companies are just platforms and anti-graft work has little relation to us. The authorities can directly contact those who publish information," he said, adding that all the companies can do is delete information which is proven to be false.

A civil servant, in his 20s from Northeast China's Heilongjiang province, said he was not afraid of being investigated and is willing to be supervised by the public, but admitted he was concerned about unfounded, malicious attacks that could undermine his standing and reputation.

"At present, social media is a popular way of exposing corruption. It will put a certain amount of pressure on those who commit these crimes, but should never have a negative effect on those who are doing a good job," said the unnamed employee.