In flood-prone Bangladesh, schools that float

|

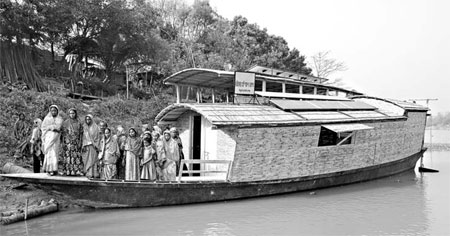

Women taking adult classes gather on a "floating school" in Bangladesh. Below, in a classroom on one of the boats. Photograph by Amy Yee |

NASIAR KANDI, Bangladesh - One morning, about 20 fourth-graders sat in two rows of desks, their textbooks open to a Bengali poem. One student wrote on the blackboard in the low-roofed room. This could have been any classroom in rural Bangladesh, except for the sight of an older woman in a sari, bathing just outside the open window.

The classroom was on a wooden boat moored to a riverbank near the village of Nasiar Kandi, Natore District, in northwestern Bangladesh. It is one of 20 free "floating schools" run by Shidhulai Swanirvar Sangstha, a nonprofit organization that has reached almost 70,000 children.

In Bangladesh, annual flooding can disrupt school for hundreds of thousands of students. In some areas, roads are impassable during the rainy season from July to October. In 1998, the same year Shidhulai was founded, flooding inundated two-thirds of the country, killing 700 people and leaving 21 million homeless.

According to a United Nations panel, flooding is likely to worsen due to global warming in what is one of the world's most densely populated countries, with 152 million people.

Pascal Villeneuve, the Unicef representative for Bangladesh, wrote in an e-mail, "Making sure that schools are resilient against natural disasters should be a priority for any disaster risk reduction preparedness and planning." He added, "We know from experience, getting children back into a school environment as soon as possible is the best way to help them recover from the shock and destruction of a natural disaster."

Mohammed Rezwan, Shidhulai's founder and executive director, started Shidhulai with about $500 in 1998, the same year that he graduated from the Bangladesh University of Engineering and Technology in Dhaka.

Only 22 at the time, he had no experience in fund-raising. But he checked the Internet for organizations that could help him and submitted proposals. His first boat school began in 2002.

In 2003, Shidhulai received a $5,000 grant from the Global Fund for Children in the United States, and then $100,000 from the Levi's Foundation, part of the clothing company that has factories in Bangladesh. A $1 million grant from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation in 2005 allowed Shidhulai to build more boats, buy computers, install solar power and create a central library. Last year, it added another boat after receiving $20,000 from the World Innovation Summit for Education, created by the Qatar Foundation.

The boats, about 15 meters long and 3 meters wide, can fit 30 children and a teacher. It takes three or four months, plus about $18,000, to refurbish an old vessel. An additional $6,500 a year is needed to pay for salaries, supplies and fuel. The organization now has 20 schools, 10 libraries and 7 adult education centers.

Shidhulai employs more than 200 staff members - including 61 teachers and 48 boat drivers - and 300 volunteers.

Free adult classes focus on practical issues. One afternoon, a group of women sat on a boat to watch a slide show by an agricultural expert, who taught them how to use organic insecticides.

Khadiza Begum, 27, said that over the past four years, she had learned to grow cucumber and different types of gourds, increasing her crop yields. Without the boat schools, she added, "there is no other way to learn."

The New York Times