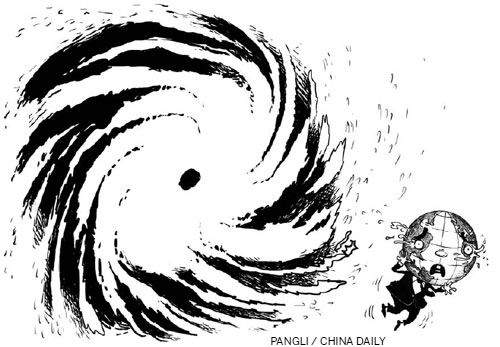

Climate madness must be stopped

At the opening of the UN climate talks in Warsaw representatives of countries from around the globe packed into the conference hall to hear the lead climate negotiator for the Philippines, Yeb Sano, describe the "unthinkable, horrific and unprecedented devastation left in the wake of Typhoon Haiyan - the strongest typhoon in modern recorded history".

In an emotional appeal Yeb told of his agonizing wait for word from his relatives, his relief that his brother has survived the onslaught and the traumatic experiences his brother had lived through over the past few days "hungry and weary, he gathered bodies of the dead with his own hands."

It was by far the most moving speech I have heard in all the years I have followed the highs and lows of the climate change negotiations. With these poignant and powerful words, everyone in the huge conference hall, which is so often devoid of atmosphere, was brought face to face with the reality of what climate change means for some of the world's poorest and most vulnerable communities across the world; and yes tears were shed by many.

While it is impossible to say whether any one storm, flood or heat wave results from climate change, scientists are clear that extreme weather events, such as Typhoon Haiyan, will become increasing likely as the world warms. There can be no more compelling reason to reduce emissions and help poor countries prepare for and adapt to extreme and erratic weather than the case put by Yeb Sano.

However, it is by no means certain that country officials sitting around the negotiating tables in Warsaw are ready to act with the urgency demanded.

People in devastated areas of the Philippines need food, water, medical attention and shelter right now. But poor communities in the Philippines, Bangladesh, Mozambique, Guatemala and around the world also need help to ensure that they can prepare for and adapt to increasingly extreme and erratic weather.

Governments can show that they are ready to take urgent climate action by agreeing here in Warsaw an international mechanism on loss and damage that addresses the impacts of climate change which it is not possible to adapt to - such as loss of life or nation.

Developed countries must also spell out how they plan to deliver the $100 billion a year by 2020 for climate finance - promised four years ago in Copenhagen - and clearly commit money, here and now, to help poor countries cope with the impacts of climate change.

Poor countries on the front line of climate change need to know this money will be available, that it won't be diverted from existing aid budgets or given as loans which they will struggle to pay back. While there is no getting away from the fact that this is a significant sum of money it's a drop in the ocean compared to the huge sums - up to $90 billion a year - rich countries spent on fossil fuel subsidies between 2005 and 2011.

As Yeb Sano said, 'What my country is going through as a result of this extreme climate event is madness. The climate crisis is madness ... we can stop this madness, right here in Warsaw."

The author is manager of the climate change team of Oxfam Hong Kong.