Days no longer numbered for abacus

While abacuses aren't big-ticket antique collector items, auction houses in China expect their value will rise following the traditional calculation device's inscription on the UNESCO World Heritage List.

Still, abacus collecting is unlike that of other antiques, such as ceramic and artworks.

"They're commonplace," Hosane Auctions Co Ltd's miscellaneous department expert Wang Kai, explains.

"Nearly every Chinese household has one."

Hosane was the only company in Shanghai that listed an abacus during its fall auction season.

The jade specimen from the 1950s sold for 5,175 yuan ($852) - far less than the 1967 postage stamp that went for more than 2.1 million yuan at the same sale.

"We only occasionally deal in abacuses, and the prices aren't high. The one that sold (at the fall auction), for example, was made to export to foreigners interested in Chinese culture."

Traditional culture doesn't value commerce as much as literature and art, Wang explains. The abacus has always been a practical tool, in contrast to the cultural and artistic connotations that impel the value of such objects as ink stones, fans and incense burners.

There are some fine jade abacuses. But the devices are usually made of wood, bamboo or ox horn. Gamblers and merchants sometimes wear tiny gold abacuses, which they believe coax prosperity.

Some specimens auction for big bucks but are few and far between, Wang says. He predicts the UNESCO listing will increase interest and prices.

Abacus collector Ge Xinhua opened Shanghai's first private museum devoted to the devices in his apartment's kitchen 12 years ago.

"The abacus' practical functions have been commandeered by the calculator," Ge says.

"People keep them for nostalgia or good luck."

The earliest historical record of the abacus appeared on the famous scroll painting Riverside Scene at Qingming Festival. Created by Zhang Zeduan (1085-1145), the 12th-century urban landscape depiction shows an abacus on the desk of an herbal medicine shop's upstairs chamber. It's clearly visible from an open window.

The oldest surviving abacus dates from between the 14th and 16th centuries, during the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644).

Ming abacuses inherited 12th-century form and structure. Abacuses were a necessity for China's merchants and clerks, until they were replaced by electronic gizmos in the late 20th century.

Ge's abacus infatuation is perhaps as rooted in his own history as his country's.

"My father died the year I was born," he says.

"My mother was 30 years old - a single mother with three children - when she enrolled in the Lixin School of Accounting (now named Shanghai Lixin University of Commerce)."

She became proficient in the abacus and supported the family as a petroleum corporation accountant.

Ge was close to an older collector, Chen Baoding. Chen left his collection to Ge when he died in his 90s.

Ge is now 63, diabetic and frail. His apprentice, 46 -year-old Liu Xiangyang, joins him to treasure hunt at secondhand markets and recycling shops.

"They're often sold for no more than 100 yuan ($16) at secondhand markets. Sometimes, you find a good one - redwood or ox horn."

Antique abacuses' values are generally not determined by age and condition as much as by material, he says.

One of his prized possessions is a rosewood model that's about 70 years old and worth about 8,000 yuan.

He donated most of the thousands of abacuses he possessed to collectors, museums and accounting institutions that publicize the device's history.

After repeated moves and donating or selling much of his collection, Ge has relegated his collection's remnants to an indoor antique market with so few shoppers that stall owners gathered around Ge when journalists arrived.

"Few people are interested in the obsolete abacus," Ge says.

"I love them. But it's just too difficult for me to hold on to my collection."

Ge's tiny shop not only sells but also repairs old abacuses. He also hawks vintage gramophones and vinyl records.

Rent costs 500 yuan a month.

"I can afford this on my police retirement pension," he says.

Across from his shop is Yang Jinmei's antique ceramic shop, where abacuses are becoming more abundant among the displayed cups, teapots and Buddha statues. Ge's apprentice, Liu, is her son.

"I want my son to learn from Ge and carry on abacus collecting," she says.

"We want to do all we can to keep the ancient Chinese calculator alive in modern times."

The 70-year-old antique ceramics dealer believes the abacus' value will rise.

"When I was young, my family was so poor that we couldn't afford an abacus," Yang says.

"I had to borrow one from our neighbor's son."

Yang once bought a small redwood abacus for her little granddaughter from an open stall for 600 yuan.

She told the girl: "I want you to keep it as an heirloom from grandma."

Wu Ni contributed to this story.

|

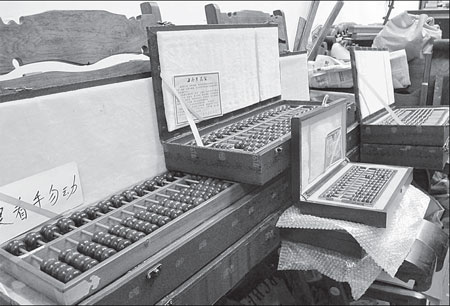

Abacuses are prominently displayed among the items at an antiques shop in Hainan province's capital Haikou after the device was inscribed on the World Heritage List. Shi Yan / for China Daily |