China's 'Sherlock Holmes' makes his case

The founder of the country's private investigation industry recalls personal dangers while campaigning for a legal status for the sector

Meng Guanggang recalls having his car set on fire and being chased by gangsters.

He doesn't take cases involving organized crime anymore. "You realize safety's value after you lose someone you care about," he says.

|

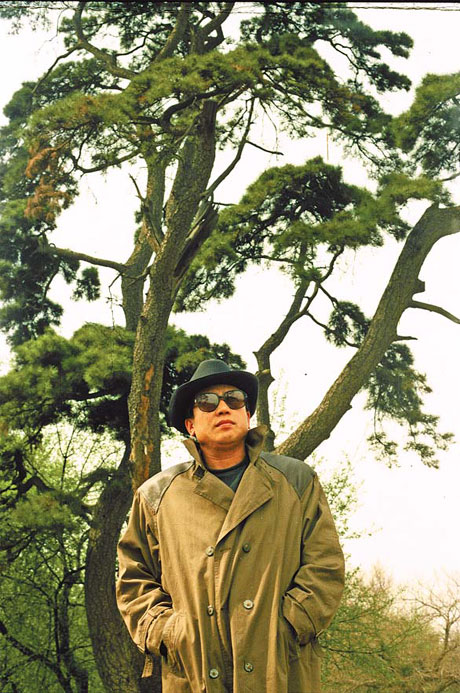

Legendary PI Meng Guanggang looks the part of a private detective with his trench coat and dark glasses. Provided to China Daily |

The 65-year-old's outlook changed after his son died of disease years ago and his wife passed away in 2008. "I made rules against dealing with extremely dangerous cases, especially involving the mob, to protect my family and private investigators," he explains. "We don't take them - no matter what they pay."

China's "Sherlock Holmes" earned his moniker by opening the country's first private detective agency in Liaoning province's capital Shenyang in 1993. Its team of 10 has become China's largest with more than 50 full-time and about 100 part-time investigators. There are more than 1,000 agencies employing 200,000 nationwide, experts say. There are no official statistics.

Meng remains a household name among insiders, who hail him as the industry's founder. Newbies still study precedents set by his early cases. And his agency's rules remain the gold standard.

The Rhino razor-blade case put him on the cutting edge a year after his agency's founding. Meng helped police bust a counterfeiting operation, enabling northeastern China's first joint venture to recover huge losses and brand trust.

His detectives initially identified a well-guarded suburban factory as a suspected production site. Plan A called for two detectives to access the factory by becoming the boyfriends of two women workers. They got in but didn't find anything solid.

Plan B worked. A detective determined the fake razors were coming from Zhejiang province's Yiwu and contacted the local procuratorate. "I pretended to be a big buyer and placed an order," Meng recalls.

"My detectives and procuratorate staffers set up an ambush. They rushed out and arrested the counterfeiters after they loaded 15 boxes into vans. We seized another 120 boxes of fake goods."

Meng was an award-winning district police station chief in Shenyang who set a record by cracking 150 cases in 40 days before he quit to become the county's first PI, he says.

The central government was then encouraging officials to become entrepreneurs. But it was a friend's business dispute that pushed him to swap jobs.

"I encountered a conflict of interest when helping friends as a cop," he says. "I didn't want people to say I was using public power to serve personal interests."

Meng and his detectives - mostly former policemen or academy or law school graduates - have since solved more than 1,500 cases. His first involved a woman whose husband often mailed money to another woman. She suspected they had a child.

Meng began with a letter the woman wrote to the man and the child's birth certificate. He found they did have a baby - but the infant died days after it was born. The woman had divorced and lost her job, and was cheating the man out of money.

"I didn't get much for that case," he recalls.

"But I was really happy the woman said I'd saved her marriage. I really hate when people say private detectives just reveal mistresses and invade privacy. Some victims are really helpless and deserve assistance and compensation."

Meng has handled more business disputes than extramarital affairs. Infidelity accounts for a third of his dealings. While business is booming, it compels "dancing with danger".

"Not everyone can do this," he says. "It's a highly demanding profession. It requires wisdom and courage. Investigation subjects often turn out to be mobsters. You face payback if you upset them."

Meng knows the legal boundaries of the profession since he's a former police officer.

Wang Tong, who started an agency in Liaoning's Dalian city, says Chinese PIs don't have the limited investigative legal powers of some of their Western peers. "So it's understandable we've used illicit methods," he says.

He points to privacy invasion. "China didn't attach much importance to privacy rights in the '90s," he says. "Work was easier then."

Meng has organized industry conferences with law professors and experts in hopes the industry can develop through self-regulation. But authorities have resisted, he says.

He has given up hope the sector will gain legal status after more than three decades. So, he's leaving.

As is Beijing detective Mu Yeyue. "I like my profession but must exit," he says. He plans to found an IT company with friends.

Meng doesn't take cases aside from some recommended by friends, and he is trying his hand at writing. "What I've done over the past decades is help people find justice," he says.

"I made a lot of money. We tried to benefit the justice system, and I still think (private investigation) is necessary."

He believes the new administration attaches great importance to the rule of law. And private investigators can be a good channel to prevent miscarriages of justice by helping the wrongly accused and convicted, and erroneously repudiated cases.

Meng believes some poor practices have tarnished the sector's image. But there's little that can be done without an industry association.

He handed his agency over to his nephew and moved to Beijing to support his son - the only surviving member of his immediate family - who studies in the capital.

Meng has published an autobiography and is working on a script. "I no longer deal with cases every day but still think about instituting the sector's legal status," he says.

"I even wrote to top leaders and got a reply. I'm hoping for the day my son can proudly introduce me as a private detective."

Han Junhong and Zhang Xiaomin contributed to this story.