Adventurers flock to Venezuela's Lost World mountain

|

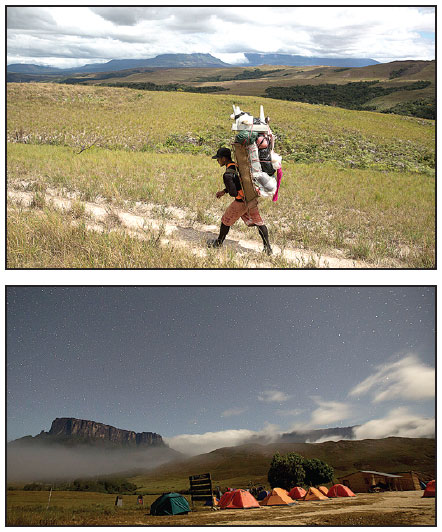

Top: A Pemon indigenous porter walks on the road to Mount Roraima. Above: The mysterious table-topped mountain on the Venezuela-Brazil border is attracting ever more modern-day adventurers. Photos By Reuters |

A mystic, flat-topped mountain on the Venezuela-Brazil border that perplexed 19th-century explorers and inspired The Lost World novel is attracting ever more modern-day adventurers.

Once impenetrable to all but the Pemon indigenous people, several thousand hikers a year now make the three-day trek across savannah, through rivers, under a waterfall and along a narrow path scaling the cliffs of Mount Roraima.

While those throngs are a boon to Venezuela's tottering tourism industry, they also scatter a prehistoric landscape with unwanted litter and strain a delicate ecosystem.

Standing at more than 2,800 meters high, Roraima is sacred ground for the Pemons and a spiritual symbol for many other Venezuelans.

"It used to be more solitary and inhospitable," recalls Felix Medina, a 59-year-old guide who has been taking people up the mountain for more than a decade.

"I still love it, but there are too many people," continues Medina, his calves aching after he led two groups up and down Roraima with the local Akanan tour agency. "It's chaotic sometimes."

Between 3,000 and 4,000 people are climbing each year, up from hundreds a few years ago.

That creates lines during peak times over Christmas and Easter, and sometimes leaves the few sheltered coves at the top crammed with tents.

Helicopters bring wealthy foreign tourists, especially from Japan, to the summit.

"It's an exotic, faraway destination so it's both very costly and very attractive," says retired Japanese diplomat Edo Muneo, 68, who like other compatriots, had to pass a physical test before leaving Japan for Roraima.

In Pemon language, the flat-topped mountains across southeastern Venezuela are known as tepuis, which means "houses of the gods".

Standing majestically next to Roraima is Kukenan, another tepui, infamous among the Pemons for ancestors who jumped off and committed suicide there.

Out of season, both mountains have the peaceful aura appropriate to one of the Earth's most ancient formations.

On Roraima's vast plateau, strange and gnarled rocks, formed when the African and American continents scraped apart, play with the mind, humorous in the sun, ghostly in the mist.

In British author Arthur Conan Doyle's 1912 classic The Lost World, dinosaurs attack a group of explorers amid the rocks and swamps of that fantasy landscape.

Today's travelers can see black frogs, dragonflies and tarantulas that are unique to Roraima, plus a range of endemic plants clinging to cracks and crevasses.

Not surprisingly, it is also an ornithologist's paradise.

Some Roraima lovers want the government, tour operators and local Pemon leaders to convene and make rules to limit the numbers who can roam the top each day to, say, a few dozen.

They would also like to see a stricter application of rules to ensure visitors, or the porters who most people employ, carry every last shred of waste down with them.