Iran deal figures in shift to East

A likely US decision to go it alone on nuclear pact could be another precursor to China's ascendancy

In 2010, my book China and the Credit Crisis: The Emergence of a New World Order, was well-received in Asia, particularly the Chinese-language version, which sold well in China. But the book's reception was lukewarm in Europe (except, surprisingly, in the Netherlands) and cold in the United States. I think the global sales pattern of the book points to the fact that, at that time, Asia's increasing prominence was much less clear to Europeans and Americans than it was to most Asians.

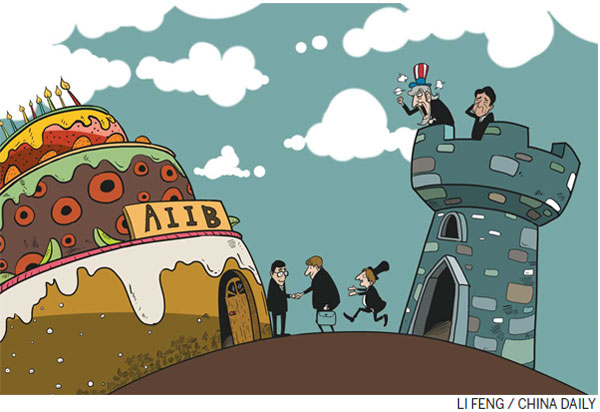

But now, in 2015, almost every month brings a fresh indication that the world's center of gravity is moving east. In March, the rush by Western nations (but not the US) to join the China-led Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank became a talking point in the world's media.

Last week, the deal reached in Geneva between the 5+1 (Germany and the five members of the UN Security Council) and Iran attracted worldwide attention.

Will the next big shock, later in April or in May, be Greece's departure from the euro currency system and the return of the old Greek currency, the drachma? This increasingly likely event would mark another major shift in the old order because it would mean the end of attempts, in Brussels and Frankfurt, to keep the euro system intact, and it would underline the weakness of the once-dominant European powers.

No one can doubt, anymore, that the world is changing in dramatic and permanent ways that were hard to imagine only a few years ago. How will this global shift in economic and geopolitical influence play out? How will the West respond, particularly the US? What will the world look like in a decade? What will China's place be in it?

The enthusiastic response by developed countries, like Britain, France, Germany and Australia, to China's formation of the AIIB shows that if a choice exists between obeying American orders to isolate China, and participating in the new global economic and geopolitical trend, the developed countries, except Japan (at least for the time being) are choosing to join China. The result is that the US has not succeeded in isolating China, but only itself.

The US's isolation may be underlined later this month or in May, when the US Congress debates whether to support the preliminary agreement reached by the 5+1 Group with Iran. It's well-known that Israel, a key American ally and a sworn enemy of Iran, would prefer for the US to remove Iran as a threat with bombs, or at least to maintain the tough and effective economic sanctions that have destroyed Iranians' living standards and brought the country to the negotiating table.

Can the Jewish lobby in America prove itself to be more powerful than the president of the US and the UN Security Council by persuading Congress to reject the Iran agreement by a large enough margin to make President Obama's promised veto of a new sanctions bill or other proposed modifications irrelevant?

It probably can, with a mixture of bribery and political muscle. But in a world that mostly supports the return of Iran from the wilderness, as a fully participating country with its economic rights restored, the US will be left only with the countries whose existence depends heavily on its support, led by Israel. Could the Europeans, China and Russia decide to ignore the US Congress, and go ahead with the Iran agreement? In this case, China will be called on to play a key diplomatic role in providing stability and communications between its neighbor Iran, the US and the other members of the 5+1.

The trend toward greater global Chinese involvement will be strengthened by the coming fragmentation of the euro, an inevitable trend unless the richer euro members led by Germany show themselves prepared to make large and continuous wealth transfers to the poorer ones. But large, continuous transfers of wealth to weaker euro members will not be accepted by German taxpayers without receiving in return greater sovereign powers, even at the cost of a collapse of the euro system.

In the absence of large transfers, Greece will have to leave the system. This now looks very likely to happen. Sustained unemployment and slow growth will force other euro members, like Spain and even Italy, to follow Greece. Even France's euro membership is in question, given its inability to reform its economy and cut its government spending deficit. In a decade, the euro may only include a few countries, or even may not exist at all.

But whatever happens to the euro, the poorer countries in southern and eastern Europe will continue to turn toward the east, and to China, which will be ready to continue investing in national and regional infrastructure that can also promote China's own interests. The economic weakness in Europe presents an opportunity to China, whose first offers to invest in Europe in 2010 were rejected by the European Commission, but which is now increasingly being accepted in Europe as an investor, particularly in Britain.

Inside a decade, we will see China and Chinese companies playing an increasingly important economic and geopolitical role in Europe, with participation across a wide range of infrastructure and industry, including high technology. China's huge pool of savings and its economic dynamism will make it an important economic partner in Europe, where opposition to a free trade agreement with China will disappear.

Elsewhere, Central Asia has already started to respond to China's large plans for economic integration and renewal, via the New Silk Road project and infrastructure investment. With hundreds of years of neglect and underinvestment, and with millions of Central Asians who lack clean water, education and other basic requirements of existence, the scope for growth is great. The re-emergence of this huge area, rich in resources and tradition, will be another expression of China's new global presence.

But in North America, Chinese influence will continue to be relatively small. US's economy is recovering because of its inherent labor flexibility, and because the US government took drastic restructuring steps early in the financial crisis of 2008, which Europeans avoided taking. As the US's economy strengthens, many Americans may follow their isolationist instincts, and prefer to go it alone. Shared economic and geopolitical interests will make the US-Sino relationship even more central to either side than it is today, but the level of tension probably won't drop very much, as many Americans continue to view China's emergence as a threat rather than an opportunity.

The tectonic plates of geopolitics started shifting in 2008, and they have moved a long way since. But the shift is not at an end. It's only just starting. By 2025, China's economy will be as large as the US's by every measure, and Chinese global influence will everywhere match that of the US. That's why the Sino-US relationship will replace the US-Europe relationship as the key axis of world peace and prosperity.

It's vital that both sides in this relationship continue to strive to understand the other, and to cooperate wherever they can, for example in the Middle East. Like two people in a three-legged race, with their legs tied to each other, China and the US cannot prosper without the other.

With widespread ignorance at the heart of the problem, and the US's tendency toward isolationism as a constant threat, the challenge will be to discover the ways in which mutual understanding and respect between China and the US can be promoted. Rejection of the deal with Iran by the US Congress would not be a good start to this process.

The author is a visiting professor at Guanghua School of Management, Peking University. The views do not necessarily reflect those of China Daily.