Treasures from the past

|

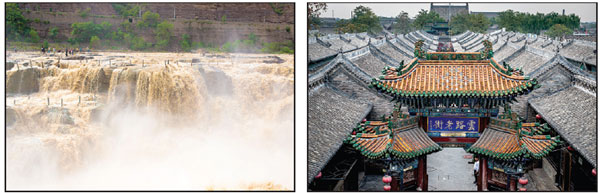

Clockwise from top: A view of Pingyao; Li Family courtyard. KHALID SHARIF / FOR CHINA DAILY; big iron oxen of Pujindu. Reinhard Klette / For China Daily; the Yunlu old street in Pingyao; the Hukou waterfalls. KHALID SHARIF / FOR CHINA DAILY; the Fenhe River park in Linfen; Pingyao ancient city. Harri Jarvelainen / For China Daily |

For those interested in the evolution of Chinese history, Shanxi is a place to go

On the walls of a redundant factory shed in the shadow of the medieval walls of the Chinese city of Pingyao, a fading big character slogan extols the proletarian virtues of hard work, efficiency and safety first.

The workers are long departed and, in a Chinese example of a familiar trend in urban renewal, the shed now provides exhibition space for cultural events such as the annual Pingyao International Photography Festival.

The walled city is at the geographical heart of China's northern Shanxi province, an area the size of England and Wales with a population near to 36 million and an economy founded on coal. It also contains a heavy concentration of the country's cultural and archaeological treasures, dating from the emergence of Chinese civilization along the Yellow River more than four millennia ago to more recent relics of war and revolution.

One of the exhibits at this autumn's photography festival was dedicated to the employees of the state-run Shenhua mining company, celebrated in an accompanying blurb as "the idol of the miner group in China". Straight-backed operatives in pristine uniforms stand against backdrops of airy workshops and gleaming machinery. The captions speak of their aspirations to "have a car within three years" or to "own a modern repair plant".

Until recent years, the reality for many miners in China's biggest coal-producing province was much bleaker. Unregulated mining by small producers, many of them private speculators from the more prosperous coast, fed China's inexhaustible appetite for raw materials but also left a legacy of child labor, environmental degradation and industrial disasters.

More than 270 people died in a mudslide at a Shanxi iron-ore mine in 2008, while the previous year the Shanxi city of Linfen topped a blacklist of the most polluted places in the world. These proved to be a turning points. After earlier faltering attempts to control the activities of the free-wheeling mine barons, the provincial authorities finally stepped in to nationalize their holdings.

Smaller mines and associated polluting industries were shut down in a strategy that, coupled with cleaner energy policies nationwide, led to fewer deaths and cleaner skies.

The downside was a slump in revenues. Shanxi was the only Chinese province where the economy actually shrank at the end of the last decade. Now that some of the smoggy pall has lifted, provincial officials have turned their attention to promoting tourism to bridge the fiscal gap.

It sounds like a tough sell, particularly in terms of luring Western visitors from the well beaten track of Beijing, Shanghai, the Great Wall and Yangtze River cruises. As recently as 2001, a well-regarded guidebook to China dedicated barely three of its 700 pages to the province, noting in passing that Linfen was a "small, rather bleak town".

For those interested in the evolution of Chinese history and culture, however, the province is a potential treasure trove. Aside from its established heritage sites, new finds are being made in the fertile loess sediment of the Yellow River plateau in the south that offer fresh insights into the origins of Chinese civilization.

The malleable soil, now leveled into terraced fields, made an excellent environment for building underground dwellings and cliffside caves from prehistoric times onwards. Even today, millions of northern Chinese live in caves, now well-equipped and brick-fronted, that are a familiar feature of southern Shanxi.

Pingyao is one of three Shanxi destinations designated as a World Heritage Site by UNESCO, which describes it as an exceptionally well-preserved example of a traditional Han Chinese city. The grid of narrow streets behind an imposing 3.4 kilometers of walls dates back to the 14th century.

The focus is the ancient government building, containing a court, tax houses and other administrative buildings that reflect a Chinese imperial tradition that lasted into the 20th century. Not just empire, but also commerce - the offices and homes of bankers who set up shop in the 19th century are among the protected wooden buildings. As local guides predictably tell Western visitors, Pingyao was once China's Wall Street.

The charm of Pingyao is that a lively market and the small workshops and homes near the ancient walls give it the feel of a living city. Artisans have revived the skills of Tuiguang lacquer work to produce traditional boxes and screens and functional modern furniture. At one workshop, men were executing the delicate compositions with fine brushes made from human and cow hair. The women were doing the heavy-duty, bare-finger polishing with ground pumice, brick dust and sesame oil.

With tourism in mind, Pingyao has a street of noisy bars, although the staff may have to send out if anyone actually orders a drink. Better perhaps to head for the tranquillity of a traditional courtyard restaurant.

Shanxi stands at the salty end of the varied Chinese culinary spectrum. Vinegar is regarded as an elixir and the noodle is king��the sliced noodle, the knife-cut noodle, the scissor-cut noodle. A Shanxi noodle virtuoso will take a 2-and-a-half-kilogram lump of dough and a handful of flour and, in a few minutes of twisting and twirling��too fast for the eye to follow��will transform it into a 12 kilometer length of diaphanous thread.

A banquet setting might include a syringe-size phial with a miniature straw protruding. What is it? "Old" vinegar. What to do with it? Drink it as a restorative aperitif.

Apples and peaches are also among the province's prides. The fat fruit are individually wrapped while still on the tree for presentation and protection, and then caringly presented at roadside stalls as if they were porcelain. Train passengers setting off from southern Yuncheng for the mid-autumn "Mooncake" festival in late September were carrying boxes of the prized Shanxi fruit or a plastic jug of old vinegar.

Most visitors to China have heard of the Terracotta Warriors of Xi'an but how many know of the equally remarkable Big Iron Oxen of Pujindu? These four magnificent solid cast iron beasts, weighing up to 75 tonnes each, once served to anchor a wooden bridge at an important Yellow River salt-exporting port during the 7th-10th century AD in the Tang era.

The river has changed course many times since then. Although discovered in the mud by locals in the 1970s, the oxen were only raised two decades later and first went on display on a raised outdoor plinth in 2005. Even more remarkable than the oxen, cast locally using the lost-wax technique, are the male figures that accompany them. Their fluid muscles, acrobatic stance and knowing expressions are reminiscent of Rodin but created more than a millennium ahead of the French master.

At Hukou, the Yellow River that divides Shanxi��"west of the mountains"��from Shaanxi��"the land west of Shan" thunders through a narrow gorge. It is a favorite spot for Chinese trippers. Although the colorfully dressed muleteers who ferry visitors down to the falls swear they see many Western tourists, there were few in evidence in late September. They remain enough of a novelty to be politely drawn aside for a souvenir photograph with children, grandmothers and wives.

As recently as this spring, Chinese archaeologists announced they had identified a previously excavated site near Linfen as the capital of the first Chinese kingdom. Three decades of research at the neolithic settlement of Taosi at the foot of Chongshan Mountain had already revealed China's earliest copper and bronze artefacts. According to Wang Wei, head of archaeology at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, experts have now concluded that the 2.8 million square meter site was the seat of the third millennium BC Emperor Yao, a previously mythical ruler lauded in later Confucian texts for his benevolence and diligence. "The site has the earliest kingdom relics we've found in the middle reaches of the Yellow River," Wang announced.

The tranquil farmland of Taosi belies the importance of the site. A narrow road through fields and orchards, flanked by carpets of drying maize, leads to a converted shed that acts as a visitor center. A small exhibition of facsimile artefacts illustrates the emerging styles of Chinese pottery, bronze and jade and primitive calligraphy.

Some of the city that lies beneath the loess has been uncovered to reveal elite tombs and other urban construction dating back to 4,200 BC. A decade ago, archaeologists located the remains of an ancient observatory��China's oldest��that matched Emperor Yao's legendary reputation as an astronomer king. Experts have recreated 13 pillars that once directed the sun's rays at midsummer and the solstices. The site is immediately reminiscent of Stonehenge, where ancient Britons were erecting their bluestone circle in exactly the same era.

A visit to Shanxi is a visit to China's ancient past, whose civilizing and even religious traditions have re-emerged as models in the modern state. Outside Yuncheng, at the largest Temple of Guan Yu, the second century AD general deified as the Daoist God of War, young and old kneel to offer incense at a state-protected shrine reconstructed in the 18th century. Visitors leave offerings of fruit, spirits, paper crowns, cakes, bolts of cloth and dried sausage, only to retrieve them once they have soaked up good luck from the god.

Elsewhere, there are reminders of a more recent turbulent past. In a quiet corner of Pingyao, a uniformed and decorated octogenarian, Lishen Cun, was holding court. His latest medal commemorates this year's 70th anniversary of China's victory over Japan. He was 12 when he joined the militia and was at the fall of Nanjing. Fingering a deep bullet scar in his forehead, he recalls killing the first of his enemies at 13, one of 32 to die at his hands. His wife smiles lovingly at a story she has heard many times before.

At the Li Family courtyard north of Yuncheng��in reality more a small village than a courtyard��the Lis presided as businessmen and benefactors until almost the middle of the 20th century. The scion of the family raised children there with his British wife at the time of World War I. A solid door with a complex lock mechanism guards the entrance to one of the elegant courtyards. Sometime in the past, some unwelcome visitors lost patience with the lock and hammered a ragged hole into the woodwork. They were a squad of occupying Japanese soldiers. According to a caption posted by the door, the stout barrier held.

Harvey Morris is a veteran journalist who has worked for the Associated Press, Reuters, the Independent and the Financial Times.

harveymorris@outlook.com