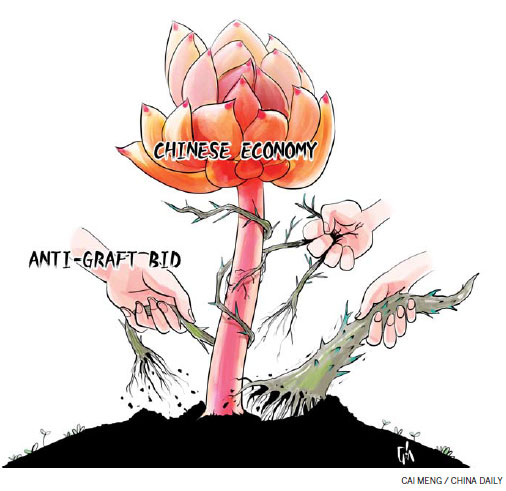

Anti-graft storm propels growth in long run

During a trip to a coal-producing province, I found that officials at a road checkpoint played cards and the loser paid by working extra hours instead of handing over money. Before 2012, it was just the opposite - they quarreled with each other in order to work extra hours.

The reason for their change is simple: In the past, they could ask coal truck drivers for bribes, a practice that has been stopped with the implementation of the anti-graft campaign in October 2012.

They are only a few of the officials "discouraged" from "working hard" by the anti-corruption drive. Before, many officials were busy promoting local GDP growth through programs like land development or polluting industries that produce immediate returns, because these programs promised promotion or other rewards for them. However, corruption often happened due to the lack of effective regulation.

As the pressure upon corruption has increased, many officials have changed their highly risky practices and now opt for safety first.

Another cause of the inactivity of officials is the canceling of some hidden sources of income for them. Exactly like in the above-mentioned case, many officials who only received average pay worked hard because it meant they could get questionable income, such as bribes. Now, with this income gone, officials tend to be less active. And the blurring of officials' job responsibilities makes things worse because they find it easy to pass the buck to one another without being punished.

Both the abnormally vigorous activity activeness and laziness of officials are caused by a lack of regulation over their power. So the officials that were overactive in the past when there was profit to be made from development programs are lazy now that there isn't.

Theoretically, officials deserve the chance at promotion or other encouragement when they do boost local economic growth. Officials are mortals, too. The key problem is to prevent officials from abusing their power and violating residents' rights or interests for their own illicit profits.

The healthy mode is: When an official boosts growth he or she gets promoted, and when he or she obtains illicit money there is certain, inescapable punishment.

In late 2015, the central authorities began striking at the "laziness of officials" and amended the Party regulations so that they would be punished. That move shows the top leadership's determination to solve the problem by regulating power, and we expect more moves this year.

A wider concern about the laziness of officials is whether it has a negative effect on the economy.

That worry is unnecessary because true prosperity can never be based on corruption, which is a kind of social injustice. When bureaucrats get rich at the cost of benefits to the public, it discourages ordinary people from working hard, thus widening the social gap and curbing economic growth in the long run.

In some states in Africa and Central Asia, for example, where officials lead luxurious lifestyles paid for with illicit income while the residents remain poor, economic growth is rather slow. In nations with cleaner politics, such as Northern Europe, they enjoy prosperity even amid bad natural conditions. Clean politics enables the residents to get their fair share from economic growth, and encourages them to work harder to support that growth.

Clean politics also promotes economic growth by cutting unnecessary costs. Without bureaucrats illicitly profiting from businesses, the whole society saves costs and cultivates mutual trust. That also enables businesspeople to better trust each other in their dealings, which also helps propel the economy. Therefore, it is not necessary to worry about economic growth being curbed - the anti-graft storm will only promote growth in the long run.

The author is a professor at the Zhou Enlai School of Governance, Nankai University. The views do not necessarily reflect those of China Daily.