Violence rages on as gangs declare war on police

As police Inspector Alba Guevara Lopez's officers fanned out through the narrow alleys of a gang-controlled neighborhood in this San Salvador suburb, half had their faces hidden by black ski masks.

"Those who live a little closer are scared that they might be identified and later face reprisals when they're off duty," said the 20-year police veteran, her face visible behind a pair of sunglasses. "In your free time you become more vulnerable."

There is reason to be afraid. Hyper-violent gangs declared open-season on police in this Central American nation in response to a government crackdown that began last year. Killings of officers nearly doubled to more than 60 in 2015, and so far this year 15 officers have been slain, including two on Tuesday. In some cases they are targeted while they're off duty and relaxing with family members, who also become victims.

Analysts say the growing attacks are a sign El Salvador's conflict is spiraling out of control and threatening to explode into open warfare.

"The gangs have managed to provoke a psychosis and paranoia within the police," damaging the force's already low morale, said Jeannette Aguilar, an expert on gangs who is director of the University Institute of Public Opinion at Central American University in San Salvador.

It's also part of a chain of eye-for-an-eye killings and retaliations that has put the country on a path toward far greater bloodshed, she said.

El Salvador had the world's highest homicide rate outside war zones in 2015, with 103 slayings per 100,000 residents. In the first three months of this year there have been more than 2,000 killings, putting it ahead of last year's pace.

The bloodshed has sent thousands of Salvadorans streaming toward the United States. Last week the UN refugee agency called for immediate action to help those fleeing violence in El Salvador and neighboring Honduras and Guatemala in numbers not seen since the region was wracked by civil wars in the 1980s.

Aguilar sees 2015 as a watershed moment in El Salvador's violence as both the government and gangs pursued strategies of more open confrontation, and even ordinary citizens took up arms to hunt down gangsters.

Gangs set up training camps in the mountains and exploded a car bomb in the capital. They began targeting police and their loved ones as well as soldiers when the army became more involved in the fight.

In just three weeks in January, gang members were blamed in the slayings of an officer's father, a soldier's brother, the wives of two police officers, and a woman and her son who were relatives of an officer.

Last month, special forces soldier Carlos Enrique Ramos was slain along with three family members he was visiting in a rural area. They were found with hands and feet bound, their bodies riddled with bullet and machete wounds. Authorities said the Barrio 18 gang controls the area.

For Guevara, it's personal: Several of the inspector's colleagues have fallen victim to off-duty murders that she's sure were carried out by gangs. One officer was at home sweeping his patio, "totally relaxed." The other was fixing his roof.

|

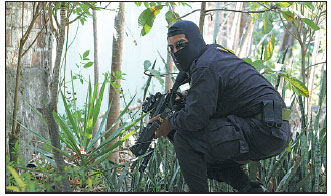

Amasked and heavily armed policeman crouches as he patrols a gangcontrolled neighborhood in San Salvador, El Salvador. Hyperviolent gangs declared openseason on police in this Central American nation in response to a government crackdown that began last year. Alex Pena / Associated Press |