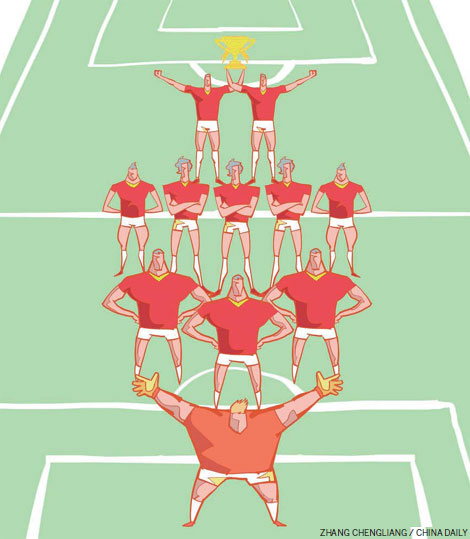

Chinese football finally taking shape

Success of CSL would go a long way to facilitating sustainable growth, turning clubs into homegrown brands

The recent rejuvenation of the Chinese Super League is an exciting development. With the support of the central government and a bold development plan backed by serious private investment, Chinese football may finally be on the right track after several false starts.

The new CSL season is generating an unprecedented buzz around the world. During the winter transfer window, barely a day passed without a fresh story in the Western media speculating on the latest big-money transfer move from Europe to China.

CSL clubs embarked on a staggering spending spree at the turn of the year on players like Brazilian midfielder Ramires, who left Chelsea for Jiangsu Suning for 25 million pounds ($35 million; 31 million euros), and Colombian striker Jackson Martinez, who joined Guangzhou Evergrande in a surprise 32 million pound move from Atletico Madrid. Over the winter, the Chinese clubs' combined spending exceeded 200 million pounds, comfortably outperforming the notoriously spendthrift English Premier League.

In the absence of a wage cap or the equivalent of UEFA's financial fair play regulations, CSL clubs, all 16 of which are owned by commercial entities, are free to offer huge transfer fees and wage packages to attract foreign talent.

Premier League teams have long had their pick of foreign stars, but the CSL's newfound purchasing power means they can outcompete them, as Jiangsu Suning did by snatching Brazilian Alex Teixeira from Liverpool's clutches for 38 million pounds.

There appears to be more substance to this latest phase in the CSL's development, a more sustainable trajectory than the previous false dawn symbolized by Didier Drogba and Nicolas Anelka's brief sojourns toward the twilight of their careers.

The X-factor, or perhaps the "XJP-factor", appears to be the personal interest that President Xi Jinping has in the game, and his ambition for Chinese football to succeed both domestically and nationally. State investment in football infrastructure, and a plan to make China a truly great sports nation with a huge sports market, has encouraged billionaire businessmen like Jack Ma and Wang Jianlin to invest in the sport, alongside a title sponsorship deal with Ping An insurance (at 150 million yuan a year compared with just 5 million yuan from Pirelli in 2010) and relatively lucrative domestic TV broadcasting rights.

It is not just about business either. In April, the government announced new proposals designed to encourage the development of the sport at the grassroots level, with the aim of establishing China as the dominant national team in Asia by 2030, and a world-leading football power 20 years later. The strategy includes plans to create a three-tier amateur competition system that involves clubs in 100 cities and more than 50 million players, and the development of 70,000 new pitches across the country.

The CSL has come a long way since the first professional league was launched in 1994, the old Marlboro Jia-A league, when enterprises were first permitted to buy clubs. The former Dalian Dockyard team, for instance, was bought by Wang Jianlin's Dalian Wanda conglomerate and went on to win eight titles before it was wound up in 2012. Jia-A became the Chinese Super League in 2004 after enduring a number of scandals.

For much of its existence, the quality on the pitch has been uneven, symbolized by the failure, until three years ago, of a Chinese team to win the Asian Champions League. Five-time reigning CSL champion Guangzhou Evergrande Taobao won the Asian Champions League in 2013 and 2015, and reached the semifinals of the Club World Cup last year before bowing out to Barcelona. Signaling Chinese interest in the competition, Alibaba e-auto recently signed a sponsorship deal with the ACL until 2022, during which time it will be hoping a Chinese club wins the title.

Success on the pitch would go a long way to facilitating sustainable growth, turning football into a middle-class entertainment product and clubs into homegrown brands. Chinese clubs have their "ultra" fans, but the challenge is to convert a much larger cohort of lukewarm observers into loyal followers, to foster a football culture and create robust clubs.

Crucially, the CSL must be free from corruption, after match-fixing and other scandals engulfed the league in 2004 and 2010. Sports betting is hugely popular in Asia, particularly on football, and CSL must guard against the curse of match-fixing if it is to generate faith in its product.

The scale, diversity and intensity of Chinese investment across the world is astonishing. China's recent entry into world football should thus be seen as another component of its global engagement strategy, alongside energy, infrastructure, agriculture, finance, tourism and education, among others.

Its presence started tentatively but has been steadily growing in the consciousness of Western football fans. I remember when Chinese players Sun Jihai and Fan Zhiyi first signed to play in the Premier League in 1998 for Crystal Palace, and Li Tie's move to Everton in 2003.

Sun famously went on to sign for Manchester City in 2002, creating a lasting link between China and the club that was cemented by Xi Jinping's visit to the training camp during his UK state visit last year. Sergio Aguero's selfie with Xi and British Prime Minister David Cameron was one of the year's most memorable images in the UK. The Chinese connection to European football has intensified markedly in recent times, with investment in Atletico Madrid and Espanyol in La Liga, Den Haag in the Dutch league, Sochaux in France, and of course Manchester City in the UK.

Chinese shirt sponsors have started to appear around the European leagues. I did a double take when I read Sina Weibo in Chinese characters on Villareal's shirts. Across football grounds in Europe one now sees advertisements in Chinese, often for betting companies or club merchandise. This year, for the first time, a number of clubs painted Happy New Year in Chinese on stadium steps.

It is now de rigeur for European teams to schedule preseason tours and tournaments in China. Four of the last seven Supercoppa Italiana matches have been played in China, including a Milan derby in front of 80,000 fans at the Bird's Nest Stadium in 2011. The atmosphere was electric; the equal of a match at the San Siro.

Unfortunately, for now, European fans won't be able to watch live Chinese football, and the next step for the CSL is to secure a foreign TV deal, something that is more likely with players like Gervinho and Fredy Guarin playing. It may even justify the 400,000 pounds per week in wages reportedly being paid to former Paris Saint-Germain star Eziquiel Lavezzi.

Some Chinese cultural products have been "lost in translation", but football is the world's game, requiring no cultural interpretation. It is also particularly popular in regions where China's global engagement is most intense - Africa, South America and Europe. As a vehicle for soft power, football has a distinguished history. Brazil's national image is inseparable from its football culture, while England makes much of its footballing tradition.

China has also had enormous success in harnessing sport for national pride. The Beijing Olympics was a resounding triumph not just for the flawless infrastructure and stunning opening ceremony, but also because China dominated the medal table.

Yet for all its fine results in Olympic swimming, gymnastics, shooting and weightlifting, the Chinese national football team has underperformed - or at least the men's team has. While the women's side won the Asian Cup in 1997 and finished second in the World Cup in 1999, the men's team has struggled.

I was as excited as anyone when the men qualified for their first and so far only World Cup finals in 2002, and was disappointed when they quickly exited the tournament having failed to score a goal. The men's team is currently ranked 96th in the world, behind minnows Guatemala, the Democratic People's Republic of Korea and the Faroe Islands, although the team is still alive in the battle to qualify for the World Cup in Russia in 2018.

There is a long way to go if the men's national team is to fulfill Xi's ambition to regularly qualify for World Cups and to perform creditably should it host a future tournament, as is hoped. But the political will is there, and with investment in pitches, training academies like the new $200 million Evergrande Football School, foreign coaches, sports science and medicine, it should only be a matter of time until we see improvements in the national team.

The author is associate professor and director of research at the School of Contemporary Chinese Studies, University of Nottingham. The views do not necessarily reflect those of China Daily.