Experts helping Ethiopia to grow

The tires crunch on the gravel, kicking up thick dust. Usually, only buses travel this remote road in Ethiopia, which ends in Alage, meaning our car attracts much attention, especially from the local children.

Although autos may be rare around here, Chinese faces aren't. Experts from China have been visiting Alage Agricultural Technical Vocational Education and Training College for 15 years.

The first delegation - 30 people, many of them doctoral supervisors - arrived in 2001, the year the institution opened, and spent three months devising a curriculum and a set of textbooks and practical handbooks. Since then, every year, the college has welcomed groups of between five and 19 Chinese experts, who stay for up to 10 months to help with teaching and to promote agricultural technology.

|

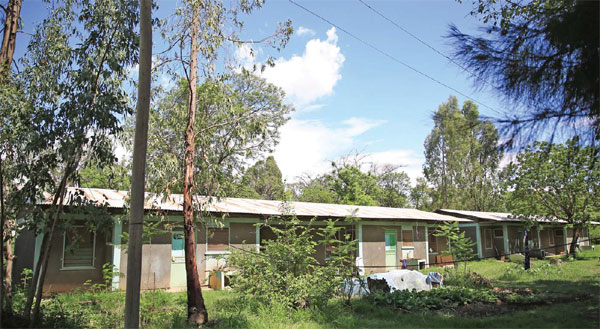

Dorms of Chinese experts at Alage Agricultural Technical Vocational Education and Training College in Ethiopia. Photos by Hou Liqiang / China Daily |

Zhang Maoqing, who heads the eight-strong Chinese team now at Alage ATVET College, says they are also reaching out to local communities through training projects and demonstrations.

Life isn't easy for these visiting experts, though. The nearest town for buying daily necessities is Bulbula, 50 kilometers away, while the capital, Addis Ababa, is a further 190 km to the north.

Before the experts were given two cars to use in 2012, they had to travel into town on the school bus. And even now, they still grow their own vegetables, as the markets only tend to sell tomatoes, cabbage, onions and potatoes.

"If it's not urgent, we usually just stay on campus," says Zhang Junyou, an expert in animal husbandry from Nanyang, Henan province, who adds that the roads are so rough that flat tires are common. He arrived in Ethiopia in 2014 after spending five years with agricultural projects in Nigeria and Malawi.

"The biggest problem here is boredom," he says with a sigh.

Even communication with the outside world is tough. Because of the poor internet connection, it took me five days to reach Zhang Maoqing and arrange a visit. Her cellphone was regularly out of service, while messages sent through WeChat, the instant-messaging app, failed to reach her.

She tells me that the 4,200-hectare college campus was connected to the web three years ago, but it can be accessed only in the main compound, which is a good 4 km from the faculty dormitories. Heavy rain and winds also regularly play havoc with the cellphone signal.

The agricultural expert from Shaoshan, Hunan province, first visited Alage in 2002, when she stayed for a year. "There were 18 teachers in that team," she recalls. "There was usually no power after 7 pm, and we had to make a fire to cook as we didn't have any gas."

He Wang from the Hunan Institute of Aquaculture Research has worked at the college for four years and says the longest power failure she experienced lasted a week.

Although cuts to electricity and water supplies still happen, conditions on campus have improved a lot, especially after a visit by a Chinese government delegation in 2014.

"Some members of that group burst into tears after using our toilets," Zhang Maoqing recalls. "At that time, we also had only one television set to share between more than five dorms."

As a result, the delegation decided to grant $10,000 to the experts of the program, part of a series of projects funded by China's Ministry of Commerce to aid agricultural development in Ethiopia. The money was used to buy TVs, refrigerators and water heaters.

Iron Lady vs nature

To carry out their work, the Chinese experts at Alage ATVET College say they have to deal with Ethiopia's dry climate, poor water retention facilities and hungry wild animals. However, their collaboration with African counterparts has already seen positive results.

Aquaculture researcher He says students wanting practical experience used to have to travel to a farm more than three hours away (and that's without the bus breaking down), as the college had virtually no facilities. "It meant those doing majors in aquaculture could only study theory rather than practical skills," she says.

So, in 2013, she proposed building fishponds on campus - a tough task given the lack of machinery and experienced engineers needed to do the job. Yet with help from a team of 100 college employees, 300 students and more than 30 teachers, He says the first pond was complete within four months.

"Many teachers and students here had never before seen the support facilities needed for the fishpond, such as the sedimentation basin, water inlet and spillway hole," she says. "The engineer complained to me that I was always giving him tasks that he'd not done before. Also, sometimes I had difficulties in communicating with the local workers when there was no one around to interpret for me, so I had to do it myself to show them how the work should be done."

The project led to He being given the nickname "the Iron Lady", but she says she was moved by the support of her colleagues. Many teachers acted as translators, while senior employees also brought food for a celebration at the construction site when the work was finished.

The pond, which covers 200 square meters and is 1.5 meters deep, "saves the college a large amount of money", He says. "Instead of going to a farm 50 km away, the students can come any time to carry out experiments or observe the water quality and fish activity."

Of course, the pond soon attracted local wildlife foraging for food. To prevent the fish from being eaten, the area was fenced off and a net was placed over the water to stop diving birds.

Wild animals are a common problem, the Chinese experts say. Those who helped to develop a demonstration center for the college's plant science department recall having to chop down 125 trees to make a fence strong enough to prevent animals from getting in and eating the seedlings. Birds also regularly target the center, which is used to grow crops including corn and teff, an indigenous grain.

Another challenge is the scarce rainfall in Alage. It rains on average once every 15 days between June and October, but in the dry season the area can go months without seeing a drop, according to Zhang Maoqing.

To address this problem, the Chinese team used its funding to build a reservoir covering 20 square meters and 1.5 meters deep.

However, the lack of materials and limited funding means introducing new techniques and technology to the area, which is not easy.

Yushanjon Memet, who arrived in Alage in November, believes the local climate is perfect for cultivating Hami melon, a cantaloupe-like fruit grown in his native Xinjiang Uygur autonomous region in northwestern China.

"It gets good sunshine, so Hami melon can be harvested several times a year," says the academic with the Xinjiang Academy of Agricultural Sciences. "If they get the technology and solve the water shortage problem, there is the potential to export Hami melon and watermelon to countries like Saudi Arabia."

However, when he tried to introduce drip irrigation at the plant demonstration center, which would ease the water shortages, he initially found it a real struggle to acquire the right materials.

Su Xuejun, an expert in soil and fertilizers from the Guangxi Zhuang autonomous region, had similar problems when he wanted shading nets for some seedlings. In the end, his search took him to Addis Ababa, but even there he had to settle for standard nets, not those for agriculture purposes, and was charged roughly five times the price he expected to pay.

Zhang Junyou had to bring most of the materials he needed to build chicken coops with automatic water systems from China, including the tools, water tanks and troughs. He says the only thing the college campus had was the chicken wire.

"I also had to train the engineers and workers before they started the construction so they would know how to build them," he adds.

Learning curve

Since 2001, China's Ministry of Commerce has sent 405 experts to work in the African nation's agricultural colleges, according to data used in a recruitment advertisement for its aid projects in Ethiopia.

This group has taught more than 50 specialized courses, transferred more than 70 technologies and trained more than 50,000 teachers, students and agricultural technicians, the information states. It adds that the ministry aims to recruit 20 teachers a year for such programs between now and 2020.

Zhang Maoqing, the team leader at Alage ATVET College, says there are currently 17 Chinese experts across three Ethiopian agricultural colleges who share a fund of more than 800,000 yuan ($123,000). The money is used to cover expenses for training, materials and experiments, as well as five cars.

"The funds barely cover our needs," adds Mei Yubin, an expert from Yongzhou, Hunan, who started his fourth stint at the college in 2012. He has worked in Alage off and on for the past 15 years.

Ultimately, the Chinese team attaches the greatest importance to training and raising the practical skills of both students and teachers, as evidenced by their work building fishponds, advanced chicken coops and a silkworm farm.

Genanew Abera Teshome recently graduated from university and works as an instructor in the college's animal science department. He says there is huge difference between what he studied at university and what he has been learning from the Chinese experts.

"I learned only theory, almost nothing practical (in university)," he says. "I've gained many practical skills while at the Alage college from the Chinese. I enjoy working with them. Now I help them with their work, and I can help society after I leave the college."

Temertu Sahlu, a vice-chancellor at the school, speaks highly of the Chinese team: "It's the Chinese government and Chinese instructors who started the training program here. It's been really supportive. In agricultural technologies, we're very poor; we don't have many instructors who can facilitate the training program. It's because of the Chinese that we're able to run these programs."

The demonstration centers the visitors have helped set up are "very useful for the practical training of students and the transfer of technologies" to surrounding communities, he says. "Before we had fields and farms, but they are not that useful for training. They have only traditional systems.

"It would be helpful if we could have more Chinese instructors, because we're getting useful technologies from them. The major thing I want to underline is that we're benefiting."

Sahlu says the college has began to train local farmers and small-business owners in the technologies shared by Chinese experts, which he feels will be put into use in a year or two.

houliqiang@chinadaily.com.cn