Classical art market growing

The Grand View sale of old Chinese artworks made 667 million yuan, exceeding the modern art total for the first time since the sale's launch. Lin Qi reports.

On May 15, the Grand View night sale of Chinese paintings and calligraphy, staged twice a year by Beijing-based China Guardian Auctions, saw a packed salesroom. So those who arrived late had to stand in the back. When the first part of the sales event - comprising modern works - ended, many walked out of the room, leaving dozens of empty seats.

But that meant the most exciting part of the auction was just about to get started.

The second section, comprising classical works, typically referring to pieces produced during and before the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911), generated three big transactions that night.

Jushi Tie, a letter by Song Dynasty (960-1279) politician Zeng Gong, grossed 207 million yuan ($31 million); a calligraphy album in caoshu (a running script) by Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) calligrapher Song Ke sold for 92 million yuan and an album of calligraphed Buddhist sutras, poems and paintings by Tang Dynasty (AD 618-907) and later scholars fetched 57.5 million yuan.

In the classical art section - where 15 of the total of 45 pieces remained unsold - the total takings were 667 million yuan, exceeding the modern art takings for the first time since the Grand View sale was launched in 2011.

The results of the Grand View sale reinforce the impression that the market for classical Chinese art, which has been stable over the past decade, is growing.

The classical Chinese art market is becoming bigger slowly even as other categories, including contemporary art and modern Chinese paintings and ceramics that used to produce record prices in the boom years around 2008, have continued to slide.

This is because of sluggishness in the Chinese art market since 2014 as the country's economy cools, driving away buyers looking for quick profits.

Jushi Tie was sold to Chinese media mogul Wang Zhongjun and the buyer of Song Ke's album is Zhang Xiaojun from Shanxi province. Both are avid collectors of contemporary art, and hence their successful bids were seen as surprising.

But Beijing-based art market expert Ji Tao said in a recent blog that collectors are diversifying their purchases, and the successful bids by Wang and Zhang indicate that due to a shortage of quality contemporary works, they are now looking at other genres such as classical pieces that are rarely seen on the market yet boast a sound provenance and are cataloged in important inventories compiled by academic authorities.

The sale also showed a steady market for Chinese calligraphy works, especially those from the Tang, Song and Yuan (1271-1368) dynasties.

Ren Wen from the Beijing-based Art Market Monitor of Artron says few works of these three periods exist and even fewer come on sale as most of them are in either public museums or the hands of top private collectors who are not very likely to sell.

So, when a piece like this appears in sales rooms, it inevitably sparks a bidding war, pushing up the price.

Market watchers also say that the sale of Jushi Tie could be considered a one-off and one should not expect the classical Chinese art market to erupt based on this one transaction.

Classical Chinese art is often referred to as a category with rather high entry barriers. In this genre, buyers need to be knowledgeable about Chinese history and its cultural traditions, which helps them cultivate a discerning taste.

They also need to invest a lot of time researching the subject so that they are less likely to be cheated.

Zhu Shaoliang, a collector of Chinese paintings, says that the classical artwork market is meant to be a niche one.

"The majority of its top pieces are already in art galleries and museums, while the modern Chinese painting market still has a quality supply of works."

He also says modern ink art attracts a bigger group of potential buyers because it deals with more everyday subjects and is thus easier for people to appreciate.

Typically, a robust art market also relies on potential buyers being educated about the subject to better recognize the value of China's artistic legacy, and not be focused on just one or two iconic works.

A good example of the obsession with iconic pieces was seen when the Palace Museum held the Precious Collection of the Stone Moat exhibition last year.

At that time, visitors endured hours of waiting just to see the Qingming Shanghe Tu, a 12th-century painting known as one of the top treasures collected by the museum.

But after the work was replaced with other equally important but lesser-known works at the exhibition, the number of visitors to the exhibition dropped noticeably.

Explaining the decline in the visitor numbers, Yu Hui, a researcher with the Palace Museum, says the Qingming Shanghe Tu attracts a lot of viewers because it is an iconic work, but the other works, largely literati paintings, require an understanding of Chinese art history.

To counter this phenomenon, he suggests that more study material on classical Chinese paintings and calligraphy be included in school texts so that the younger generation get a complete picture of how Chinese ink art has evolved.

Contact the writer at linqi@chinadaily.com.cn

|

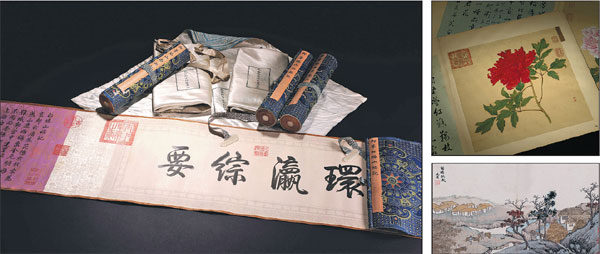

Above left: Essays on Baita Mountain, written by Qing Dynasty (16441911)emperor Qianlong, sold for 116 million yuan ($19 million) in 2014. Above right: Parts of Qing court painter Jiang Tingxi’s flowerandbird album (top) and Ming Dynasty(13681644)painter Shen Zhou’s landscapes that are auctioned in Beijing this month. Photos Provided To China Daily |