Producer who kowtows for screenings

A drama to save a cinematic work of art with little mass market appeal unfolded both on-screen and off-screen when a venerated producer pleaded for more screenings of the swan song of a master. Raymond Zhou writes.

A week after Song of the Phoenix opened, it garnered a paltry 3 million yuan ($454,000) in box-office takings, barely enough to cover the marketing cost. Now, a month after its May 6 opening, it has collected 85 million yuan, a rare feat for an art-house film. What happened in between was an eye-popping act by its 63-year-old producer, a man whom I have known for a while, and whom I talked to recently in a post-screening dialogue.

Fang Li was in tears when he saw me. My eyes were moist, too, as were those of many in the audience. I hugged him, a true hero who almost single-handedly saved what Martin Scorsese calls "a lovely little film by a giant in filmmaking".

Yes, what happened off-screen was just as dramatic, if not more so, as the story on-screen.

On May 12, when the screening rate of the film dipped below four per 1,000 screens, Fang knelt down and begged China's film exhibitors for more screenings.

The real-time video went viral.

|

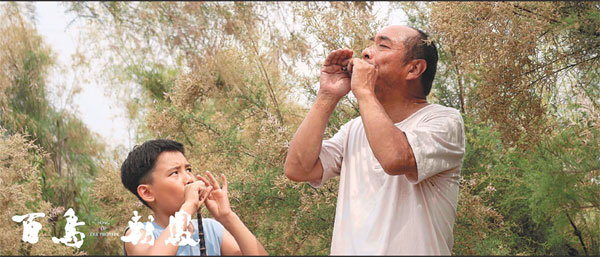

A scene from the film Song of the Phoenix featuring veteran actor Tao Zeru in the main role. Photos Provided To China Daily |

Then, as people flocked to movie theaters across the nation, its screening rate shot up, to 10 percent at one point, way past the first-week performance, which is usually the peak for any film.

Some suspected that the video was a marketing ploy, but Zhang Wei, vice-president of the China Film Criticism Society, provided details that confirmed the incident.

Shortly before what's now called "the 80-million-yuan kowtow", Zhang and a bunch of students were with Fang, and they extolled the latter's integrity in continuing to support the country's quality films.

"He was touched, and maybe he drank some wine afterward," says Zhang.

|

Fang Li talks about "the 80-million-yuan kowtow" in a recent post-screening event. |

Fang brushed this off, saying "Had I known my act would have this result, I would not have waited a week before kneeling."

Fang told me that his act was inspired by the internet meme "guiqiu" - a humorous term that literally means to kneel down and beg - rather than by an ancient practice in China, which carried more solemnity and self-debasement.

"I would not do it even for my own films," says Fang.

When River Road, a quiet, beautiful film he funded, grossed less than 1 million yuan in 2014, he did not think of begging the exhibitors.

Even though he is one of the producers of Song of the Phoenix, he has no financial stake in the film. He calls himself "a volunteer producer" who provided resources, including some marketing expenses and his team, as a donation.

Fang's act was for Wu Tianming, the director of the film.

Wu, a renowned filmmaker whose credits include Old Well and Life, a hugely influential work from the 1980s, is widely considered the godfather of China's fifth-generation directors.

When he was in charge of Xi'an Film Studio back then, he broke convention by bankrolling rookies like Zhang Yimou.

For those asking the hypothetical question "Would Wu have knelt for more screenings?" the answer is here - as studio head Wu knelt to beg mediocre peers to not hoard resources so that talented newcomers would have a chance.

Wu died in 2014, a few days after Song of the Phoenix was completed.

His daughter, Wu Yanyan, then tried to sell her father's swan song to China's distributors - with no success - until she met Fang.

Fang was trained as an earth and ocean scientist and earned an MBA in the United States.

He has a business in Silicon Valley, but started to produce films, mostly art-house fare, early this century.

His biggest project was the 2014 directorial debut by best-selling author Han Han.

The Continent grossed a whopping 632 million yuan.

However, Fang does not agree that he makes "art films".

He tells me that the films he has produced, including Song of the Phoenix, belong in the genre of "drama".

He defines "drama" as movies that tell stories and "art films" as experimental works with thin plots.

Yet, Chinese translations are so confusing that little distinction can be made by a layperson with no knowledge of nuance.

Whatever label one may place on it, Song of the Phoenix has now gained three layers of meaning, making it ripe for future film treatment.

The story is about a patriarchal musician who plays the traditional Chinese instrument suona, a high-pitched double-reed with a sound similar to the oboe.

The master is meticulous about passing on the technique - and the social stature associated with it - to the next generation.

But he is chagrined to find that he could be the last of the line because modern, Western instruments, represented by a brass band in the film, have eroded suona's popularity.

In a similar vein, Wu Tianming was from a dying breed, insisting on making films that are personal rather than popular.

Unlike his protege Zhang Yimou, Wu did not switch to so-called commercial films. Now, Fang has taken up the baton, believing that if "films with a soul" (in Fang's words) are made, people will turn up to watch them.

At least half of China's filmdom endorsed the film, ranging from pop idols like Lu Han and Fan Bingbing to royalty-like figures Ang Lee and Feng Xiaogang.

Zhang and Martin Scorsese each taped a short recommendation, which are shown before the film.

Had they all charged for their endorsements, the fees would have added to billions of yuan.

Even critics who noticed flaws in the film refrained from publicly pointing them out. Still, the public did not show up. That should give pause to anyone who pays big money for celebrity endorsements.

I joked with Fang that he had used the most effective trick in promoting a small film.

Other forms have been used before, such as open letters or a boisterous fracas with exhibitors, but none has had much effect.

Still others have proposed setting up art-house cinema chains, a platform that's going out of fashion even in developed countries.

Fang has an innovative idea: He wants regulators to place a cap on the screening rate of every film, Chinese or foreign, for instance, a maximum of 30 percent of screens for any film and a minimum of 3 percent.

"That would guarantee diversity," he says.

Contact the writer at raymondzhou@chinadaily.com.cn