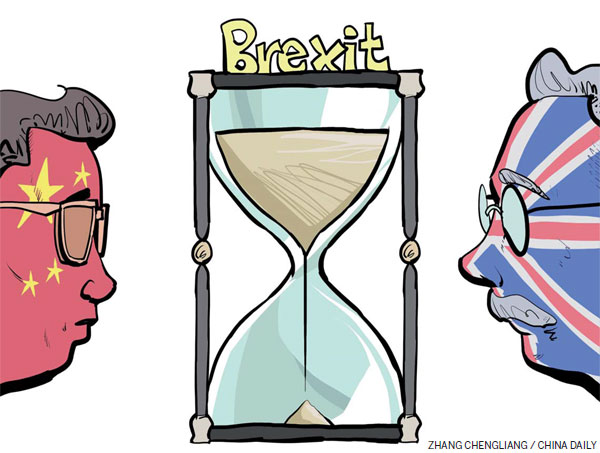

Brexit effect yet to be determined

Damage may be limited or aggravated by the terms of the exit, and Britain's success in trade ties with countries such as China

For three days in October, the United Kingdom rolled out the red carpet for a Chinese delegation led by President Xi Jinping.

Queen Elizabeth held a lavish state banquet to welcome the Chinese president. Alongside the discussions on increased trade and investment between the two countries, Xi was taken by Prime Minister David Cameron to visit a top football club and a traditional English pub, where the president steeled himself to drink a pint of English beer.

Both China and Britain hailed Xi's visit as raising their relationship to a new level. This was marked by China's equity participation in a British nuclear power station, and by Britain's early involvement - contrary to the wishes of its senior partner the United States - as a founder shareholder in the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank created and led by China.

On June 23, the British shocked the world by voting decisively to leave the European Union after 43 years of membership. Cameron, who had welcomed Xi to London in 2015, had arranged the national referendum to solve the deep split over European membership within his own Conservative Party. His miscalculation on the outcome led to his resignation, which immediately followed the result.

Today, several politicians are fighting over the right to succeed Cameron as leader of the British Conservative Party and prime minister, with the final result becoming known in September. A general election will follow toward the end of this year, in which the new prime minister will seek popular support for his or her government.

China has not been the only country to be attracted by Britain's openness to foreign investment, its flexible labor market, its strong legal system and English language, and London's global leadership in financial services - enhanced by British membership of the EU, the world's largest market for goods and services. Fast-developing Chinese multinationals like Huawei Technologies Co have followed numerous banks and multinationals from many countries outside Europe in making Britain their European home.

But Britain post-Brexit, although still the world's fifth-largest economy, may not present the same compelling case for economic partnership for foreign investors as before. Britain's decision to leave the EU must cause dismay in Beijing.

By making the United Kingdom one of its key partners within Europe, has China backed the wrong horse? This must be the question the Chinese leaders are asking themselves.

The answer will depend largely on two things: first, the departure terms agreed by Britain with the EU, particularly regarding Britain's post-Brexit access to the single European market and the ease with which London-based financial institutions can continue to operate inside the EU; and second, Britain's longer-term success in creating a global economic footprint, based on developing trade relationships with important countries outside Europe like India and, yes, China. This longer-term development in turn depends on Britain's political leadership. But questions have emerged over Britain's leadership post-Brexit.

It was widely expected that Boris Johnson, the former mayor of London and prominent advocate for Brexit in the run-up to the referendum, would succeed his former school and university classmate Cameron as prime minister in order to lead Britain forward into its unknown post-Brexit world.

But Johnson's leadership campaign was suddenly derailed by his campaign manager Michael Gove's decision to run for the leadership position. This dark act of political assassination has been attributed to Chancellor George Osborne, a close friend of Gove, a former education minister and Johnson's partner during the campaign to leave the EU.

This development has resulted in the current minister for home affairs, Theresa May, becoming the front-runner to become the new prime minister. In her six years as home secretary in Cameron's government, May has developed a reputation as a fierce protector of her own and her department's interests, rather than being a far-sighted and especially competent home affairs minister. Her own support of remaining in the EU before the referendum raises a question mark over her ability to lead Britain successfully out of the EU.

The friction and disorder within the government following the referendum is mirrored within the British nation as a whole, with the "We're the 48" movement organizing a march in London to present their case for a rethink (the "48" refers to the 48 percent won by the Remain in Europe vote in the referendum). Many of these are the people in the middle - business people, doctors and farmers, of middle age, with large mortgages on small houses, and children being educated at expensive schools, who cannot afford much higher interest rates or an economic recession. It seems likely that this group will continue to express its shock and horror at the prospect of Britain leaving the European Union.

Whoever becomes the new British prime minister, for China, much depends on the architect on the British side of the new Sino-British relationship, Osborne, remaining as an important member of the next government. If Osborne stays on as chancellor or moves to another important position within the government, like foreign secretary, then Britain's continued fostering of the China relationship is highly likely.

If not, it's possible that within Britain's political establishment, other views less favorable to China might gain the ascendancy, even though Britain's post-Brexit focus on its global trading relationships surely highlight the significance of the Chinese relationship. The good news for China is that, although nothing is certain in politics (as Johnson's demise has demonstrated), Osborne is likely to remain a significant force within British politics for the foreseeable future.

Although Britain will probably work out a post-Brexit solution with the European Commission to preserve some of the benefits of being an EU member, in the field of financial services, both Paris and Frankfurt are casting a greedy eye over London's strength in financial trading, settlement and associated services, particularly in the field of law. Here, it's unlikely that a London outside the EU will be able to maintain its financial dominance. Outside finance, large Japanese and American multinationals like Microsoft, Toyota and General Electric may decide to move their European centers of gravity to countries within the EU like Ireland, Belgium, Germany or France that have financial services infrastructure.

But Britain's position both culturally and geographically between the European mainland and North America, with strong historic ties to the Middle and Far East and Australasia, should go far to maintain its continued global importance. As a rule, Chinese prefer to pursue long-term friendships. Now that the ice has been broken between Britain, which remains one of the West's most influential societies, and China, the main Asian power and leader of the newly emerging world, the Sino-British relationship will probably continue to be of real economic and strategic significance to both sides, with or without British membership in the EU. Much depends, however, on how Britain handles its new status, and how the British economy evolves over the next five or so years. The early signs are not particularly promising.

The author is a visiting professor at Guanghua School of Management, Peking University. The views do not necessarily reflect those of China Daily.