Oxford gets into China history act

US editor explains the 'nice arc' from 1550 to present day in a book that has chapters by leading experts

Jeffrey Wasserstrom says it is a challenge to be a historian of China because it is a country where history always matters.

"I think history has always been seen as significant on multiple different levels," he says. "One of the first tasks of each new dynasty has been to write a history of the previous one and use the story to explain or justify the new arrangements. The historian has a special role."

|

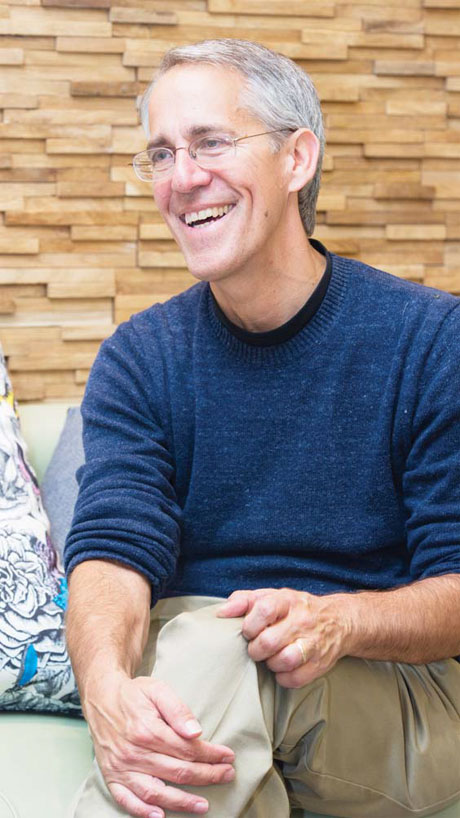

Jeffrey Wasserstrom says Oxford wanted the book on Chinese history to be used as a textbook but also an enjoyable read. Nick J.B. Moore / For China Daily |

The 55-year-old leading China expert from the United States was speaking at Bedford Hotel in London, where he was appearing in a series of events to launch The Oxford Illustrated History of Modern China, of which he is the editor.

The book, which has taken four years to produce, is the first significant Oxford history of China. Cambridge University, seen as the birthplace of Sinology and where Wade and Giles invented the first romanization system for Chinese, has its own famous history of the Middle Kingdom.

"It (Oxford) has never done big China projects. They wanted it to work on several different levels - a book that could be used as a textbook but also one that is an enjoyable read," he says.

Slightly smaller than a coffee table book and beautifully illustrated, it covers the period from 1550 with China in the ascendancy during the late Ming period to the present day.

"There is a nice arc to that period. It goes from a period when China had a relative centrality and strength in the world to the present - another period of relative centrality and strength. It is a different kind of arc to most modern histories that begin with the Opium wars around 1850 when China was in decline.

"They (Oxford) originally suggested doing a history from the beginning of time but I thought that was too daunting a prospect."

Wasserstrom, who wrote the introduction and a chapter dealing with the 1990s, himself selected the authors, some of the leading writers on China today. They include Rana Mitter, director of the Dickson Poon Oxford University China Centre, and Robert Bickers, who specializes in the so-called humiliation period of the late 19th century.

"I gave a list and I also had to convince the authors to do it. I was looking for people who had shown some knack for trade or popular writing."

He believes the first chapter by Dutch social and cultural historian Anne Gerritsen on the late Ming and the early Qing period is among the best.

"She was one of the ones with the least track record for high-profile writing but I knew she was a beautiful writer. I love all the chapters but I think hers is quite special."

Although the book is chronological, all of the chapters stand alone in their own right and contain interesting analysis of the period they focus on.

"When you are trying to reach the general public, I think the challenge is how you make analytical points but wear the analysis lightly so that the reader feels as though they are just being taken along by an interesting story," he says.

Wasserstrom, who was born in Palo Alto but mostly grew up in Santa Monica, made his first connection with China as an undergraduate at the University of California, Santa Cruz.

"It was a liberal arts system so you could dabble with a lot of things. It (the university) was already teaching Chinese, which was pretty unusual, and I found it fascinating so I stuck with it."

He went on to do a master's in East Asian studies at Harvard University and then a doctorate at the University of California, Berkeley, where he came into contact with the great China historian Frederick Wakeman, who was a major influence.

"He was a wonderful storyteller and he had written some of the books I admired," he says.

Wasserstrom has held academic posts at both Kentucky and Indiana universities before moving in 2006 to the University of California, Irvine where he is now Chancellor's professor of history.

He has also worked for the American Historical Review and the Journal of Asian Studies but is perhaps most widely known for his previous well-regarded and insightful book, China in the 21st Century: What Everyone Needs to Know, of which there is to be an updated third edition next year.

That the book is an Oxford effort but edited by an American brings into question the debate as to whether there is a difference of approach between the study of China in the UK and the US.

"I think in the US, historians who write on China are more fully integrated into history departments whereas here (in the UK) some are part of China studies. It is not a clear divide. Tim Cheek, who does the 1980s chapter in our book, is originally from Australia, educated in the US and teaches in Canada so there is a lot of mobility."

Wasserstrom says it can be difficult creating interest in the histories of non-Western countries, although China is at least becoming an exception to that.

"I did an a event at King's College in London recently with other historians, including Sunil Khilnani, who has just done a big book on India, and we were talking about the Western interest in the histories that we all study," he recalls.

"One of the speakers worked on Indonesia and said that there was at least some level of interest in China and India. She said people didn't have any knowledge whatsoever of any single event in Indonesian history, despite it having more than 100 million people."

Wasserstrom says this can be true of China with the Taiping Rebellion being less well known that the American Civil War, which took place at almost the same time.

"Yet it is dramatic and interesting. The leader thinks he is (Jesus) Christ's younger brother. You would think that was something just made up for a movie script."

Wasserstrom's next major project is going to be a history of the 1900 Boxer Rebellion, which he believes is a much misunderstood period of Chinese history.

He says it is still best known in the West from the 1963 Charlton Heston film, 55 Days at Peking.

"The thing about the Boxer Rebellion was that they didn't really box and they weren't really rebels. They were loyalists and they used martial arts. They supported the dynasty and the dynasty decided to use them."

andrewmoody@chinadaily.com.cn