Tangshan earthquake 'changed everything'

China Daily photographer Wang Wenlan recounts how, as a young soldier in 1976, he documented the city's unforgettable moments of pain

The lives of Lu Guilan and Wang Wenlan mingled for a few minutes on Aug 9, 1976.

For more than 12 days before that moment, Lu, a mother in her 40s, had survived under debris by drinking her own urine and the rainwater that seeped through the cracks of the fallen bricks.

|

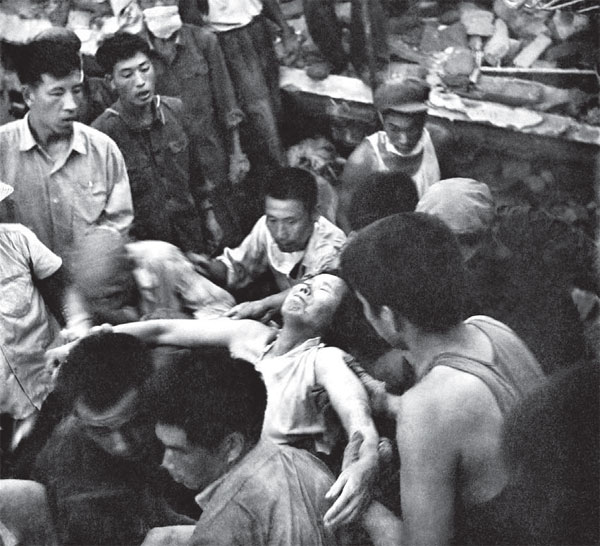

Lu Guilan is rescued by soldiers after surviving under wreckage for more than 12 days. Photos by Wang Wenlan / China Daily |

She had become trapped after the deadliest earthquake of the 20th century hit Tangshan, Hebei province, at 3 am on July 28, 1976, killing more than 240,000 and crippling another 16,000.

Wang, then a 23-year-old army photographer captured the moment rescuers carried Lu out, her eyes shut and limbs stretched out.

"The long exposure has given the picture a slightly soft focus. I later used strong film developing fluid in order to heighten the image," says Wang, now vice-chairman of the China Photographers' Association. "The result is stark immediacy accentuated by a raw sense of history."

The 63-year-old still vividly remembers the journey to Tangshan, 200 kilometers north of Beijing.

"We set off at 9 am, six hours after the earthquake, yet traveled for 20 hours due to all the damage done to roads and bridges," he says. "When night fell, there was a deadly silence - for most people, the fight for life was over.

"Occasionally, there would be the sound of wheels grinding on the rugged and ruptured ground. Seriously injured people, and probably remains, were being carried away on carts."

Given all that, the survival of Lu was a sheer miracle. "Eight days into the rescue, soldiers had stopped finding survivors. Then, at noon on the 13th day since our arrival, I was told that a trace of life had been discovered underneath the crumbled structure of a hospital," says Wang, who immediately rushed to the site. "With no heavy machinery, all the digging had to be done by hand."

The effort went on for seven hours. By the time the last concrete slab was about to be lifted, he put down his spade before taking up his camera.

"It was 7 pm. Night had started to invade, but there was still enough light for a picture," says Wang, who on the morning of that very day had checked out from a makeshift hospital.

The hospital was no better than some tents amid a sea of rubble. "I was lying there for a week. Malaria was strongly suspected, since all of us had been drinking from a nearby swimming pool since day one," he says. "At one point, with swarms of flies droning overhead and the mixed smell of rotting bodies and sterilizing bleach in our nostrils, I seriously thought about death. But then a doctor inspected me and suggested drinking iodine tincture."

Initially resisting the idea, Wang obliged after being told that his entire stomach was festering and that he had no other options.

"After drinking it for three days, I recovered, just in time to take Lu's picture," he says. "Needless to say, my fellow soldiers suffering similar symptoms took up the treatment."

Wang's unit stayed in Tangshan until early December that year, when all the survivors had been relocated. "Between July and December, I left Tangshan twice, once to fly to Beijing on a small military aircraft to buy film, another time to return to my camp in Dingxian, where I had some film developed for printing," he says, adding that in total he took about 1,000 pictures.

Most images, including the one of Lu's rescue, were published only in 1986, when Tangshan commemorated the earthquake with a photo exhibition.

"By the time I took the pictures, in 1976, the 'cultural revolution' (1966-1976) had not yet ended," says Wang, referring to the political movement that kept China in turmoil for a decade. "Everyone of us with the army was expected to be politically conscious, which meant never showing a vulnerable side to the 'enemy' in the West.

"But when you were there, soaked to the bone in despair, you realize instinctively that something needs to be done to record and preserve the history, however heartbreaking and unbearable it may seem."

One of Wang's pictures shows a young woman weeping as she sits on a bed outside of a makeshift tent made of cardboard.

That picture was also included in the 1986 show, which provided an occasion for the photographer to meet Lu.

"She told me she was looking after her hospitalized husband when the earthquake struck. The man, who had been lying in bed, died instantly, while Lu survived by hiding under the bed," Wang says. "It was comforting to know her children had also survived and that, by the time I visited, she had become a grandmother."

The last time Wang went back to Tangshan was five years ago. "The city is as modern as I can reasonably expect," he says, yet he has no doubt that the memory of the earthquake still haunts.

"The daybreak came a mere few hours after my arrival in Tangshan in 1976. As the faint sunlight revealed the full scale of the disaster, the only thing I could think about was an atomic bomb. The next few days saw sweeping wind and rain every night. It was as if nature intended to obliterate from the surface of earth any trace of tragedy.

"But like the seeping rainwater, sadness just sank in people's hearts, deeper and deeper."

He recalls a 4-year-old boy with a swollen head who had been hit by falling debris. "When I asked how much it hurt, the boy, who was holding the hand of his 8-year-old brother, simply stared back. He never cried. The brothers' parents had died.

"People say the shock had a numbing effect. The numbness would loosen its grip sooner or later. But for the boys, childhood was ended, once and for all," he adds.

Wang joined China Daily in 1980 and has continued to shoot pictures for the paper ever since.

"I first picked up a camera at 14. For the next seven or eight years, I took a lot of pictures for myself. But Tangshan changed everything. It was the first time I turned my lens toward people in pain, and toward history unraveling.

"That was really the end of a self-infatuated young man and the beginning of a serious photojournalist."

zhaoxu@chinadaily.com.cn