Trump casts a cloud over climate deal

Despite uncertainties brought by US presidential election, parties stay focused on implementation of Paris Agreement

The latest United Nations talks on climate change opened on Nov 7 in Marrakech, Morocco. In UN jargon, the meeting was referred to as the 22nd Session of the Conference of Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change.

The meeting started on a happy note at a cheerful moment, because the landmark Paris Agreement had taken effect on Nov 4, 30 days after at least 55 parties to the convention representing at least 55 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions had joined.

The number of parties that have ratified the agreement has now risen to 109, covering 77 percent of global emissions. Nearly 200 nations gathered in Marrakech to work on the implementation of the Paris Agreement.

The agreement, reached in the French capital in December 2015, aims to strengthen the global response to the threat of climate change by holding the global temperature increase this century well below 2 C above pre-industrial levels and to pursue efforts to limit the temperature increase even further to 1.5 C. Under the Paris Agreement, all parties have outlined their climate action plans - known as "nationally determined contributions" - to be implemented from 2020 and expected to be scaled up over time.

While the Paris Agreement establishes legally binding obligations for effort, it does not establish a legally binding obligation for countries to actually achieve their aims. Thus, implementation holds the key to actually achieving desired outcomes.

Delegates to the Marrakech conference worked on details of the Paris Agreement and put in place a process to design the rules and processes for implementation. While decisions on the rules and process might not have been decided at this year's conference, it can create a process that will guide countries in fulfilling and enlarging their existing climate commitments.

Financial support from developed countries has been an issue of great concern to developing countries. At last year's Paris conference, for the sake of other developing countries and the solidarity of the G77 and China as a group, China proposed and insisted on a "concrete roadmap" to scale up the level of pre-2020 financial support by developed countries to achieve the goal of jointly providing $100 billion (94 billion euros; 81 billion) annually by 2020 for mitigation and adaptation. This element was eventually incorporated into the Paris deal. China also insisted on "making finance flows consistent with a pathway toward low greenhouse gas emissions and climate-resilient development".

However, developing countries consider the finance part of the Paris Agreement too weak, lacking any compulsory language to scale up climate finance, and want it to be strengthened in subsequent negotiations. On behalf of developed countries, Australia and the UK delivered just last month a roadmap for meeting the collective target of $100 billion per year by 2020. This roadmap report suggests that public support will increase to $66.8 billion in 2020 from $43.5 billion in 2014 and would be leveraged to mobilize private finance to reach the full collective pledge. It enhances transparency on how developed countries plan to reach the collective target. The increase of climate funds and the relatively high share of public finance appear to be encouraging signals.

However, this report as well as last year's widely debated climate finance report produced by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, overestimate the net climate support provided to developing countries. Both reports also reveal the persistent neglect of adaptation needs in the poorest countries, with less than 20 percent of international climate finance going to adaptation.

The Paris Agreement specifies a balance between climate mitigation and adaptation. While balance could be interpreted differently, by any standards, 80 versus 20 percent of international climate finance would not be considered a balance between climate mitigation and adaptation.

Negotiators in Marrakech and subsequent conferences needed to agree on what should be included in climate finance, how best to account for climate financing, and what the next steps are to both increase funding for measures to build resilience to climate impacts and how to balance climate mitigation and adaptation. Related to this, agreement that the Adaptation Fund, created in the old times of the Kyoto Protocol, is given the chance for a new life through the Paris Agreement and would have helped improve such an imbalance.

The Paris Committee on Capacity Building aims to support developing countries in their climate action efforts. The committee is now up and running. Negotiators agreed that in 2017 it will focus on supporting implementation of countries' national climate plans.

While the Marrakech conference is widely viewed as a transitional COP because many issues discussed cannot be decided at this conference, negotiators remain focused and are making progress.

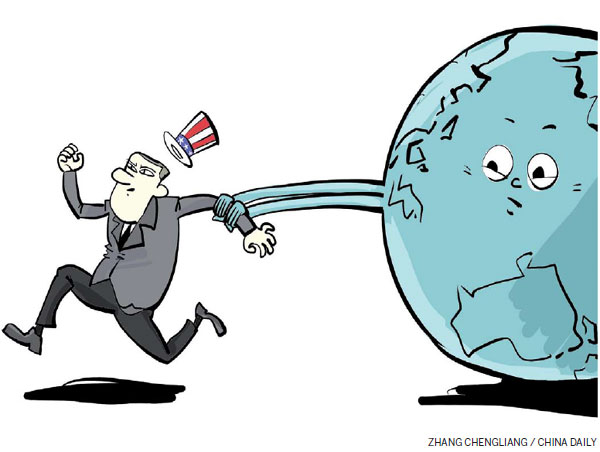

However, the unexpected victory of Donald Trump in the US presidential election caused a stir in Marrakech and creates uncertainty over what policy decisions he might make, including whether the US might withdraw from the Paris Agreement altogether.

On the campaign trail, Trump promised to cancel the US involvement in the agreement and cut the US international obligation to provide climate-related funding.

However, past evidence shows that a US president-elect doesn't always stick to what was promised as a presidential candidate. Whether this pattern applies to Trump remains an open question, given that he is completely different from any previous US president by any standard.

According to Article 28 of the Paris Agreement, it takes four years for any country to leave the UN deal. If the US decides to withdraw from the Paris accord, it will have to wait four years. Doing that, the US will pay high political and diplomatic costs.

It could be confronted with carbon tariffs imposed by other parties, on the same grounds that the US used to threaten other counties for not taking action comparable to its own.

A plausible option is that the US will remain a party to the Paris Agreement but will water down some initiatives and efforts undertaken under the Obama administration.

To what extent the US would retreat remains to be seen. On the one hand, in a bid to make the US fully energy independent, Trump does support renewable energy, in addition to fossil fuel sources. On the other hand, Trump lost the popular vote, and a large number of states, cities and counties across the US have been taking affirmative steps and making efforts in climate mitigation and wide use of renewables, even in those states where Trump won. All these may restrict the space of the Trump retreat.

Meanwhile, China and the EU should lead the global community in keeping collective pressure on the US, restricting its potential damage to a minimum. In Paris, China showed itself to be both a great collaborator and a leader in global governance. With the potential vacuum left by a US retreat, China should grab the opportunity and strengthen its role in global governance on climate change. Meanwhile, it should avoid taking on too many responsibilities that go beyond its capacity.

Zhang Zhongxiang is director of the China Academy of Energy, Environment and Industrial Economics. The views expressed do not necessarily reflect those of China Daily.