Museum displays 500 years of robots

Why do humans build machines that resemble them, and what does that say about us? To find out, a London exhibition that opened on Tuesday surveys 500 years of simple to sophisticated robots.

Take, for instance, a walking and praying monk from the 16th century or a cartoonlike humanoid avatar that helps children with autism today. They and 100 other robots on display at the Science Museum chart an evolution of machines that fascinate and terrify.

"One of the big issues with doing a show like this is people's preconceptions that robots come in, they destroy the world and they enslave us all," lead curator Ben Russell said.

"One of the advantages of taking a long view of robots, as we have done, is that you realize a lot of these concerns have been with us for a very, very long time," he added.

However, he dismissed such fears as overblown and said humans would prove "much more adaptive".

One premise of the exhibition is that studying robots is a good way to learn what society was like at any given point.

A monk statue built during the 16th century on behalf of King Philip II of Spain was designed to impress. It is able to pray, walk across a table while moving its lips and raise a crucifix.

A stunning silver swan from 1773 moves with grace, thanks to three separate clockwork mechanisms.

Science fiction has fed for more than a century on fears that humans might be overtaken by the machines they create, and the robotization that is increasingly a part of everyday life still stirs up debate.

Artificial intelligence has also divided the scientific community, with renowned physicist Stephen Hawking saying that AI could be "either the best, or the worst thing, ever to happen to humanity".

|

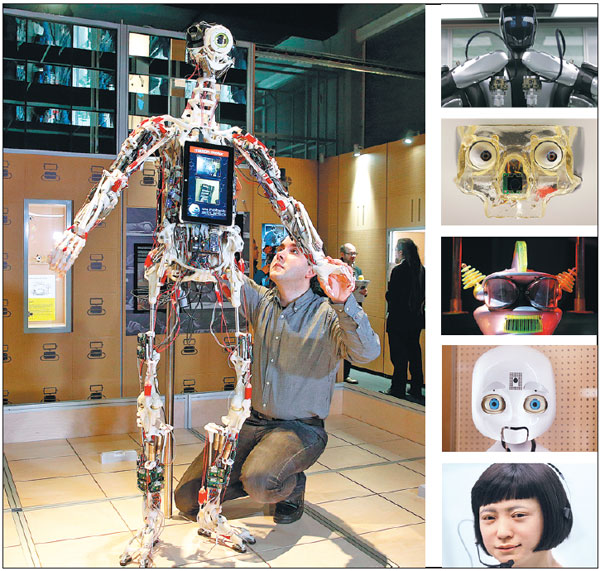

A technician adjusts an android on Tuesday for a robot exhibition at the Science Museum in London. The show features an array of robots whose faces range from futuristic to lifelike. Alastair Grant / AP |