Xi's life experiences bolster poverty fight

President's work in remote villages has given him deep insight, Xinhua reports

As the president of the world's most-populous nation, Xi Jinping has never taken the issue of poverty lightly.

In his four years leading China, Xi, 63, has visited more than 30 impoverished villages and townships, sharing his experience in poverty-eradication work and putting himself on the front lines of the war on poverty.

Looking back, it is clear that Xi's deep understanding of, and focus on, the poor has evolved throughout his political career, as he rose from the role of a young worker in a remote village in the northwestern province of Shaanxi to China's top job.

He has often spoken of his experience of living in poverty, and shared his ideas and insights about how to deal with it. He has said relocation is an important approach to fighting poverty, for example, and has highlighted the role of ecological compensation - the use of market-based methods to protect the environment - which also can boost local incomes.

Last month, during an inspection tour in Hebei province, the president said fighting poverty was the fundamental task in building a moderately prosperous society.

China has set 2020 as the target year to reach that goal, with a key goal of eradicating poverty. As Xi has said, "No one should be left behind on the road to a moderately prosperous society."

Xi's first experience with poverty came in Liangjiahe village in Yan'an, Shaanxi, nearly 50 years ago. He was not even 16 when he was sent to Liangjiahe in early 1969, as a result of Chairman Mao Zedong's campaign for urban youth to experience rural labor.

"Experiencing such an abrupt change from Beijing to a place so destitute, I was deeply affected," Xi said, recalling the whole village turning dark at night because the only light available was provided by a few old kerosene lamps.

In less than three years in Liangjiahe village in Shaanxi province, Xi had become a proficient rural laborer.

"I found myself easily traveling several kilometers of mountain road while carrying a shoulder pole weighing more than 50 kilograms," he said.

However, after a day of hard work, he had barely earned enough to buy a pack of the cheapest cigarettes.

A year's harvest could only sustain farmers for a couple of months, and they often found themselves running out of food as early as April or May. As a result, Xi and his contemporaries sent to work in the countryside were almost reduced to begging.

From 1988 to 1990, Xi worked as chief the Communist Party of China in Ningde prefecture - one of 18 contiguous poverty-stricken areas at the time - in Fujian province in the southeast.

"During nearly two years in Ningde, I went to almost all the townships, including three of the four that had no access via paved roads," Xi said.

He recalled his visit to nearby Xiadang township vividly: "The township CPC committee room was built on a renovated cow enclosure, and a big crowd of us had to hold our meetings on a bridge.

"The poor access meant few higher-level officials went to Xiadang. I was the first prefectural CPC committee secretary who had ever been there," Xi said.

In 1997, Xi, then-deputy secretary of the CPC Fujian Provincial Committee, visited Xihaigu, a region in the south of the Ningxia Hui autonomous region, an area known for its harsh environment.

Declared "uninhabitable" for humans by visiting UN experts, Xihaigu had been left out of China's headlong rush to riches through economic reform.

"The families I visited did not have enough to eat, and the drinking water - salty to the taste - was brought from afar," Xi said. The villagers did not even have the luxury of showering.

"It was my first visit to Xihaigu, and the sight of people's lives there shocked me," Xi said. "I was stunned that there was still a place with such poor and difficult conditions after so many years of reform and opening-up."

Leading by example

Xi's experience of poverty encouraged him to eradicate it for good.

In Liangjiahe village, where Xi worked for seven years from 1969, he was inspired by the success of Dazhai, a model village in neighboring Shanxi province, where the villagers harvested grain to ensure they had enough to eat. Xi and his fellow villagers dreamed of "having corn flour for meals" for the whole year.

"I had just turned 20 at that time, and I was mainly thinking about ways to allow everyone to harvest a little more grain and have a little pocket money," Xi said.

He led the villagers in digging wells, building terraces and sediment-storage dams, and setting up the province's first methane-generating pit.

He also invited the village's three blacksmiths, who had been working elsewhere, to return and set up an iron cooperative: "Forging iron generated income. Only by making money could we get things done," he said.

Of the about 30,000 young people sent to the Yan'an region from Beijing, Xi was the first to work as a Party branch secretary at the time, for which achievement he was awarded a three-wheeled motorcycle by the Beijing municipal government.

"The motorcycle was useless in the village. It was even impossible to ride it into the village. Better to exchange it for something practical," Xi recalled.

He went to the Yan'an agricultural bureau and exchanged the motorbike for a two-wheeled tractor, a flour mill, a grain thrower, a rice mill and a submersible pump for the villagers.

Rural reform

Reform took root early in Xi's thinking about governance.

From 1982 to 1985, he served first as deputy secretary and then secretary of the CPC Zhengding county committee in Hebei. "The household contract responsibility system had not been put into place when I arrived," he said.

At the core of China's last round of rural reform, the household responsibility system meant farmers could be allocated land by contract, and they were allowed to sell surplus produce to the market or retain it for their own use.

In 1983, the secretary of the Lishuangdian commune proposed piloting the system on a piece of land under his jurisdiction.

"Both I and another deputy secretary of the county committee supported him. A year later, his commune reaped a good harvest compared with the ordinary output elsewhere," Xi said. "Suddenly all the people in the county said this seemed to be a viable way, and the system was finally implemented widely.

"At that time, Zhengding was a purely agricultural county. I proposed pursuing diversified economic development and a 'semi-suburban' economic model because the county is close to Shijiazhuang," Xi said. "The county (government) set up an office for diversified economy, and I was concurrently the CPC county committee's deputy secretary and the office's director.

"The five communes south of the Hutuo River had done a good job. Many people went to work in Shijiazhuang by bike in the morning," Xi said. "In the Shijiazhuang markets, the vegetables were produced in Zhengding, the people selling brooms and simple furniture were from Zhengding, and the guardians of the boiler rooms and the gates were also from Zhengding."

When he worked in Fujian, Xi often visited families that had lived in thatched sheds and small wooden boats for generations, and would ponder how to lift them out of poverty.

"Most of the fishing boats were in a dreadful state, without electricity or running water. The boats were low, gloomy and damp. Fishermen who did not have boats just made shacks - they were hot in summer, cold in winter and it was hard to shelter from the wind and rain," Xi said.

After conducting research, he submitted a report to the CPC Fujian Provincial Committee that proposed resettling people living in thatched sheds and small boats.

"Communist Party members must have no peace of mind, day and night, seeing people living in such poor conditions," he said in 1998, when presiding over a meeting to address the problem.

Thanks to Xi's proposal, several million people bid farewell to their unstable lives in just a few years.

The CPC attached great importance to coordinated development between the advanced and underdeveloped regions. Fujian, for instance, was tasked with assisting the development of the Ningxia Hui autonomous region.

As deputy secretary of the CPC Fujian Provincial Committee, Xi was in charge of the assistance program.

"We are a socialist country. Having taken the first steps to prosper, the coastal regions in the east should not leave other areas alone. We need to achieve common prosperity," he said.

Within the framework of counterpart assistance, wells were dug and cellars built to store water for drinking and irrigation in Ningxia.

Xi encouraged researchers in Fujian and Ningxia to develop technology to improve potato yields. Residents of Xiji, a county in the south of the region, saw their incomes rise after they planted potatoes and sold them to businesses in Fujian.

The Fujian government also supported Ningxia in relocating people from impoverished areas. As a pilot project, several thousand families moved from Xihaigu to a better area near the regional capital, Yinchuan.

"The measures proved effective and we created a sustainable path," Xi said.

Targeted efforts

Whatever Xi's position, he has always valued precision in poverty alleviation.

"You should not bomb fleas with grenades," he said, stressing that money should be spent in the right places.

In late 2013, he visited a remote village in central Hunan province, where the young and robust had left to work in cities, and only seniors, children and women remained.

"I wondered how they could possibly pursue any major projects. So, I said we might as well get you some 'legs' - several black pigs, cattle and goats for every household. The senior villagers were very pleased, saying it was exactly what they wanted," Xi said.

Back when Xi served as deputy Party chief and governor of Fujian, he proposed "making real efforts to help the really poor".

Since he became the CPC leader in 2012, he has insisted on seeing "real poverty" every time he visits an impoverished region, such as Fuping county in Hebei, Huayuan county in Hunan province, and the Dongxiang autonomous county in Gansu province.

"In some localities, people have the misconception that poverty relief goes hand in hand with industrial projects. (But) in the deep mountains and forests, where there are no professionals or market and costs are high, it isn't easy to develop industrial projects," Xi said.

Poverty relief is all about solving real problems, according to Xi, who has stressed the importance of education and guaranteeing basic public facilities, such as roads, water and power.

He has also suggested teaching those in poverty "how to fish", in accordance with their actual conditions and capabilities.

"The elderly can raise chickens, ducks and sheep. Give them some fine breeds, teach them about proper feeding and offer some financial support. It's important to help young people to find jobs. (We]) train them, and instruct them to find employment outside their homes," Xi said.

He has also warned against aiming too high, saying tasks should be accomplished one by one.

Xi has led calls to save children from poverty, particularly by granting them access to education.

"In poor regions, improving education should be a priority. Children should be given a fair chance at the starting point of their lives. Give them opportunities to become educated, to go to college. Then in eight to 10 years, they will have the means to become well-off, or at least to feed themselves," Xi said.

Financial support

He has demanded more financial support be given to education programs in remote and rural areas, and that the development of compulsory education receives due attention.

Teachers could be rotated among poor mountainous areas, Xi said, suggesting offering them better pay and greater opportunities for promotion. He believes that to lift people out of poverty it is crucial to instill the aspiration to improve their own lives.

From 1988 to 1990, Xi was secretary of the CPC Ningde prefectural committee in Fujian.

"I saw Ningde as a weak bird that needed to make an early start, work with perseverance and not feel ashamed of lagging behind. Work incessantly and it will eventually take on a new look," Xi said.

Some of Xi's speeches in Ningde were later compiled into a book, Out of Poverty, which he said could serve as a guideline.

"A lack of morale will get people in poverty nowhere," he said.

"In the fight against poverty, no corruption, fraudulence or blind pursuit of political achievements can be allowed," Xi said, adding that secretaries of CPC county committees or county magistrates should work at the frontlines and make concrete efforts.

Only with a down-to-earth style and concrete efforts can cadres fulfill the promise to eliminate poverty that has been made to the people and to history, according to Xi.

He has stressed that the task of poverty relief - which tops the Party and the country's work agenda - must be assigned to the most capable cadres. Secretaries of CPC county committees and county magistrates can only be transferred to other positions once they have proved themselves through relief work.

He has also highlighted the importance of inspection and supervision in poverty relief, stressing that the effects of poverty-elimination work in one place should be evaluated by officials from other areas to ensure impartiality, and the result of the assessment should be an important yardstick for cadre promotion.

|

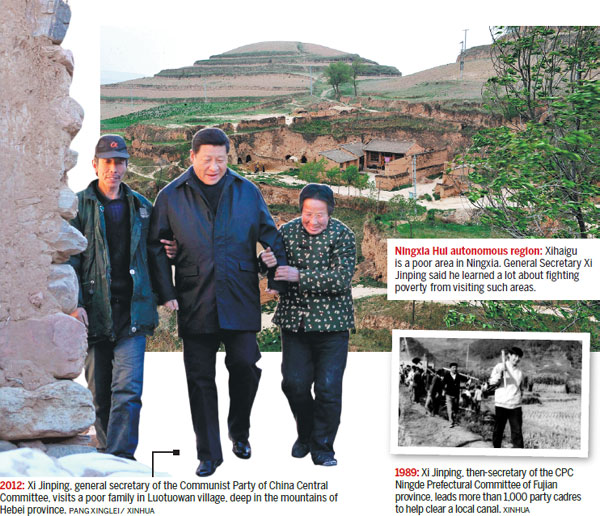

2012: Xi Jinping, general secretary of the Communist Party of China Central Committee, visits a poor family in Luotuowan village, deep in the mountains of Hebei province. Pang Xinglei / Xinhua Ningxia Hui autonomous region: Xihaigu is a poor area in Ningxia. General Secretary Xi Jinping said he learned a lot about fighting poverty from visiting such areas. 1989: Xi Jinping, then-secretary of the CPC Ningde Prefectural Committee of Fujian province, leads more than 1,000 party cadres to help clear a local canal. Xinhua |