Painting with a camera

Leo K.K. Wong's works make for a happy marriage of the photographic and the painterly. A show of representative works by the master photographer is now on in the city. Chitralekha Basu reports.

It's hard to believe Leo K.K. Wong never photoshopped an image in his more than 50 years of wielding the camera. In his rendition, lotus leaves appear in a stunning shade of cerulean blue. Plum blossoms growing on tree branches look like an intense fuschia red forest ready to erupt in flames.

The artist's steadfast loyalty to old technology seems to have served him well. Using a film camera rather than going digital allows him to manipulate the play of light on the photosensitive film roll. He says the surreal landscapes he creates are a result of allowing multiple exposures and varying the shutter speed. But then not everyone who prefers analogue over digital can invest nature with the luxuriant, fantastical, breathtaking allure that Wong seems to be able to achieve.

Extreme patience is probably at the heart of Wong's wondrous images in which lotus leaves floating on a pond glow like LED flashlights and a snow-covered landscape with a flock of herons grazing on it looks like a hand-painted Christmas card. Wong seems to have an intuitive sense of the perfect moment and the persistence to wait for hours together until he can freeze it.

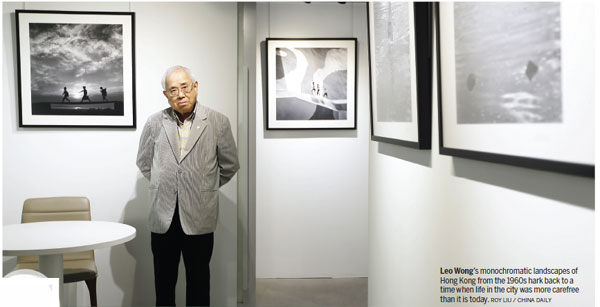

When he had begun taking pictures, way back in 1965 (a somewhat late entrant to photography at 34) he would set off for Kowloon or the New Territories at 6 am and wait there until midday, training his camera on the stream of people who went about their daily chores. He would park himself in a quiet corner of the community play areas in newly-built housing estates, or visit the sprawling beaches where the kids frolicked around without a care. Wong says he misses the sense of sheer abandon with which children played on Hong Kong's streets and other public spaces in the 1960s. At that time he shot only landscapes in monochrome - an empathetic, sometimes joyous, nod to a way of life that was slower and less stressful than the way it appears now.

Cynics might argue that Wong's Hong Kong landscapes are way too beautiful to pass off as real. Even when he is portraying menial laborers and roadside vendors, there's a dreamy, somewhat unreal quality about them.

Wong tells us he wasn't necessarily ignoring the harsh and unsavory elements of life when he went about looking for subjects in Hong Kong's fishing villages, schools and marketplaces. "At that time Hong Kong wasn't a very rich society but you can see the people were quite happy."

Besides, he says, documentation of Hong Kong life was never a priority for him, although he ended up doing a bit of that as well by default. For the same reason he took care to not leave obvious and identifiable references to the city's architecture and generic features in his landscapes.

"I have consciously avoided including Hong Kong landmarks in my photos," says Wong. "Some photographers in my time would use a wide-angle lens. They wanted to include everything, like nowadays the trend is to take shots from high above. People say these would have a historic value. Then I never thought of my photos as materials for historical reference."

Learning from the finest

In the 1970s, Wong won the International Salon Exhibitions hosted by the Photographic Society of America, nine years in a row, picking up the top prize four times. And yet his first major solo show in his hometown was not held until 2002. By that time he had re-invented his photographic persona completely, going from monochrome to color, and from landscapes to abstract, interpretative takes on nature. In between, for about 10 years, he had stopped taking photos completely, choosing to study Chinese paintings and calligraphy instead.

He seems to have sought out the best teachers when he wanted to pick up a skill. Just as his medical degrees were earned at world-renowned institutes in the UK, when it came to cultivating artistic skills, Wong learnt his craft by watching the creative processes of the best in the line. His first guru in photography was the master photographer and portraitist S.F. Dan (Deng Xuefeng). Wong also learnt from his close friend, the photographer-filmmaker Ho Fan, who could manipulate the play of light and shade on the varying street levels in downtown Hong Kong to astounding effects. So when Wong decided to create photos with a painterly feel, he turned to the Chinese master painter Zhu Qizhan for guidance. "That old man was an expert in managing colors," says Wong. "His brushstrokes were very powerful. He encouraged me to do minimalist compositions, and use symbols and suggestions."

When he took up his camera again, in 1995, Wong was back in a new avatar, producing hypnotic, surreal images in vivid, unworldly colors.

Hong Kong, says Wong, became aware of his landscapes in monochrome only after he did a joint exhibition with actor Chow Yun-fat in 2009, in which Wong's black-and-white portraits of Hong Kong from the 1970s were placed against Chow's more contemporary ones. A retrospective of his oeuvre, spanning more than 50 years, can now be seen at Hong Kong's Kwai Fung Hin Art Gallery. This is the first time Wong's work is in the market. Gallery owner Catherine Kwai informs the show has met with considerable interest from seasoned and top-level collectors, although the idea of photographs as high-value collectibles is yet to catch on in the city.

Kwai says they wanted to pitch Wong's photos as "works of fine art, with long-term collection value", a status she feels is richly deserved by a man having such a long and illustrious career. For a photographer who draws heavily on the painting traditions of China - from the splashed ink art technique to the minimalist charm of line drawings to the interplay of light and riotous colors - such recognition cannot be too far away.