Proud heritage forged in gold

|

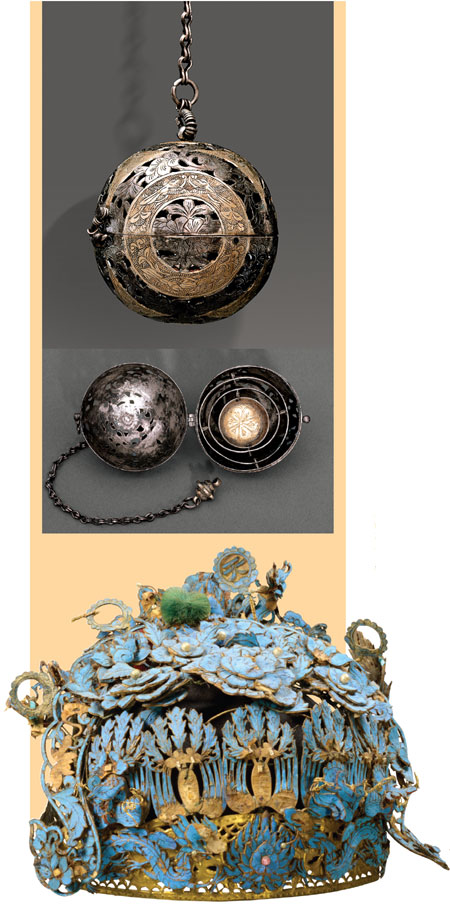

Gilt silver sachet with flower and bird patterns (left above), Tang Dynasty (618-907); kingfisher blue crown (left bottom) with dragon and phoenix design, Qing Dynasty (1644-1911). |

As surprising as it may seem, Hong Kong and the province of Shaanxi, 1,500 kilometers to the northwest, have a common heritage: The two places were at the crossroads of international exchanges, cultural and commercial.

Of course there have been differences, too. Shaanxi's heyday was between the seventh and 10th centuries when a powerful Tang Empire ruled China and many of its current surrounding regions from the province. Hong Kong, a speck in the South China Sea, would not burnish its credentials as a financial powerhouse until more than a millennium later, a century after the British colonized it in the mid-19th century.

Yet the unique cultural identity of both was minted as a result of a wind from the west - in the Tang's case - and waves of influence that constantly broke on its shore - in Hong Kong's case. While Hong Kong has remained vibrant, its culture continually forged and shaped by multiple forces, Shaanxi has settled down over the centuries, as an inner Chinese province that is relatively secluded, museums being one of the most obvious repositories of its glorious past.

And now that glorious past burns brightly in Hong Kong as the special administrative region celebrates the 20th anniversary of its return to China. Among the items being exhibited at the Art Museum of the Chinese University of Hong Kong are nearly 60 pieces or sets of goldware and silverware, whose shimmering surfaces reflect not only the artisanal development of China, but also the country's history in general. All exhibits are from Shaanxi.

"What sets this exhibition apart from everything I have organized before is that this one tells a story, first and foremost, about a particular handicraft - metalwork, and more specifically goldwork," says Bai Lisha, of the Shaanxi Cultural Heritage Promotion Center. A veteran project manager, Bai is responsible for many exhibitions outside the Chinese mainland showcasing Shaanxi's archaeological heritage.

"Before, the narrative of a show was always spun around either a historical figure or period."

The metalwork highlighted here is split into nine categories, including forging, casting, gilding and filigree, and a very special one involves the use of blue kingfisher feather.

"In choosing exhibits for the show, I needed to ensure all of these different crafts were represented," Bai says.

"Another criterion is beauty: What meets the eye and inspires the mind is infinitely more important than a particular object's historical value."

One of the highlights of the exhibition is an iron sword with a turquoise-embedded gold hilt. The sword, unearthed from a tomb dating back to the Spring and Autumn Period (770-476 BC), is held in the highest regard by archaeologists because of its beautifully wrought and magnificently mounted handle. The S-shaped turquoise was meant to symbolize the curve of a dragon, Chinese civilization's most powerful totem.

As a prelude to the Warring States Period, which ended when Emperor Qin Shi Huang united the country in 221 BC, the Spring and Autumn Period brought the rising of one power after another, all buttressed by military might. The sword seems an apt metaphor for a time in Chinese history best remembered for endless maneuvering, military and diplomatic.

Another item of particular interest is a holder for an umbrella. The catalog calls it a coupling for connecting two parts of the long handle. With gold and silver patterns set against copper, it serves to remind gobsmacked viewers of the lengths their ancestors went to in order to embellish their lives.

But of course this was just a privileged few, those who sat at the apex of the social pyramid, breathed its rarefied air and surrounded themselves with aesthetic beauty, not only in life but in death as well.

The umbrella is believed to be part of a copper chariot unearthed from the grand burial ground of Emperor Qin Shi Huang, who united China for the first time before going on to build the Great Wall.

Yang Junchang, a conservationist and expert in ancient Chinese metal craft, says the question of how the delicate, swirling patterns were produced remains open. The thread of gold, as if outlined on the copper surface by the finest Chinese paintbrush, is in fact the product of a mysterious and long lost art.

"We believe there are two main possibilities, the first being that gold was hammered into the pre-carved groove on the copperware," Yang says. "The second is that the groove was filled in with a semi-molten amalgam of gold and mercury before being heated. The result: the mercury evaporated and the gold remained. The first method would have left traces of pounding on the metal, and the second one would have left pores produced by the mercury as it escaped.

"We regard the second method as the more sophisticated, but even with the help of a microscope we have yet to discover a single piece that reveals a porous texture.

Yang says the lack of progress is the result of the very few research objects that are available to his team.

"It's extremely hard for us to borrow from museums. For example, I've never had a chance to closely inspect that coupling piece I've just been talking about."

On the other hand, modern technology has transformed the work of archaeologists and conservationists such as Yang, whose deductions used to be drawn largely from fieldwork. Between 2014 and 2016, Yang's team worked closely with researchers at the Chinese University of Hong Kong in an effort to unlock the secrets of the ancient goldsmiths. The project was funded by Chow Tai Fook, the Hong Kong-based gold jeweler long associated with the revival of ancient Chinese metal craft. Indeed, the exhibition is mainly the result of that collaboration.

"With their language advantage, our Hong Kong partners contributed partly through their research of English-language documentation," Yang says. "They were looking for evidence that might point us in a certain direction or help re-establish a long-lost link."

That link could prove crucial for the likes of Yang and Bai, who are trying to reposition their research and weave it into a broader narrative. Bai is behind another exhibition in Hong Kong, on archaeological findings and sites along the ancient Silk Road, due to open in November.

The Tang Dynasty (618-907) represented the height of that exchange, an exchange that China is seeking to revive now. In the seventh and eighth centuries, Chang'an (present-day Xi'an), as the capital of the Middle Kingdom, enjoyed a prosperity rivaled only by a few cities on Earth including Baghdad and Constantinople of the great Byzantine Empire.

Chang'an became a focal point on that nexus of trade, which took Chinese merchandise, including tea, silk and porcelain, to other parts of the world while bringing other sought-after products, for example incense, to the rich and powerful in China who reveled in their immense standing, material and social.

On display at the art museum in Hong Kong is a perfume sachet. The ingeniously constructed gilt silver ball with flower and bird pattern is a marvel of engineering. What is known today as the system of Cardan suspension was set inside the ball, keeping it constantly horizontal and preventing the perfume powder from spilling when the sachet moved with the wearer.

"Here, aesthetics are by no means sacrificed to mechanics," says Jiang Jie, director of Shaanxi's Famen Temple Museum, from whose underground storage the sachet was discovered. "Only three such balls have been found. Two are housed in our Famen Temple Museum and one in the Shosoin in Nara, Japan.

"Tang was when the very essence of Chinese culture, such as tea and incense burning, was formed."

As Jiang says this, he points to a four-legged receptacle woven exquisitely with gold and silver wire. It is a tea leaves holder, and it underscores the ceremonial aspect of tea culture.

"Most rulers of the Tang Dynasty were devout Buddhists. And Famen Temple, housing what was believed to be the tiny bone pieces belonging to Sakyamuni, the founder of Buddhism, was in effect the royal temple of worship. What was discovered in its storage - many were items of gold and silver - offers a tantalizing glimpse of a time when imagination was celebrated by a liberal society."

Bai says that the exhibits, as minute as some are, hold up a mirror to what was happening in society at large as well as in the minds of those who crafted the pieces.

"If you look at how metal art developed in China down the centuries, there is a clear trajectory of change: personal whimsy gradually being replaced by well-guided endeavor, uncorseted imagination by auspicious images, and untamed beauty by a more stunning - or stupendous, depending on how it affects you - aesthetic."

During the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911), China's last feudal dynasty, a technique called dian cui, or dipping of blue, became popular whereby the surface of gilt silver - mostly hair accessories - was covered with blue kingfisher feathers. The technique is extremely time-consuming, and the result is often a riot of colors as the resplendent blue clashes with gems of different hues.

"It is a visual feast, and one is constantly being reminded of the amount of time put into its making," Bai says.

"But something is lacking, and that, I believe, is the free spirit. Tang is not unique in its prosperity - the period starting with the Qing emperor Kangxi (1654-1722) and ending with his grandson Emperor Qianlong (1711-1799) was also marked by social stability and national power. However, the difference is that in the latter period, China's door was closed. It is only with cross-pollination that the flower of art can bloom in true splendor."

zhaoxu@chinadaily.com.cn