Elegant collision between East and West

The German philosopher Gottfried Wilhelm von Leibnitz (1646-1716) read books on Chinese society and became deeply interested in the structure of the hexagrams in the "Book of Changes." Leibnitz spoke highly of China's Confucian beliefs, and thought they influenced the enlightenment movement in 18th century Germany

Chinese drama arrived in Europe in the 18th century. In 1735, a Jesuit named Prémaire brought a translation of an old play called "The Little Orphan of the Family Zhao to France." The play was written in the 14th century and had been adapted from an even earlier piece.

|

|

|

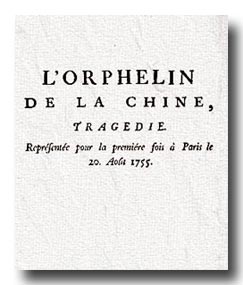

"L'Orphelin de Chine." |

One of France's most renowned writers, Voltaire (1694-1778), who was writing plays about the time Prémaire brought this translation to Paris, declared "The Little Orphan of the Familly Zhao" to be a masterpiece, far superior to anything produced in Europe in the 14h century. Voltaire appropriated the plot, calling one of his plays "L'Orphelin de Chine." In a series of influential works written between 1740 and 1760, Voltaire expounded his ideas about China.

In a novel he presented his views on the parallelism of moral values in different societies, European and Asian. In a play he suggested that the innate moral strength of the Chinese had been able to calm even the Mongol conquerors led by Genghis Khan. Voltaire reviewed world history in "An Essay on the Customs and Spirit of Nations," with a lengthy section on China. "The great misunderstanding over Chinese rites sprang from our judging their practices in light of ours: for we carry the prejudices that spring from our contentious nature to the ends of the world."

Unable to find a "philosopher-king" in Europe to exemplify his views of religion and government, Voltaire believed Emperor Qianlong would fill the gap, and wrote poems in the distant emperor's honor.

Voltaire's praise for Chinese institutions appeared in a cultural context that was intensely sympathetic to China. During this same brief period in the mid-18th century, Europe was swept by a fascination with China that is usually described by the French word "chinoiserie," an enthusiasm for Chinese decor and design rather than philosophy and government.

In prints and descriptions of Chinese houses and gardens, and in Chinese embroidered silks, rugs, and colorful porcelains, Europeans found an alternative to the geometrical precision of their neoclassical architecture and the weight of baroque design. French rococo was a part of this mood, which tended to favor pastel colors, asymmetry, a calculated disorder, and a dreamy sensuality.

Its popular manifestations could be found everywhere in Europe, from the "Chinese" designs on the new wallpapers and furnishings that graced middle-class homes to the pagodas in public parks, the sedan chairs in which people were carried through the streets, and the latticework that surrounded ornamental gardens.

King Louis XIV was said to like Chinese style furniture. Chinese furniture could also be found in the queen's room and the prince's office.

Some grand aristocratic parties even used China as their theme. In 1667, a big ball was held in the Chateau de Versailles where King Louis XIV hosted the opening ceremony wearing a Chinese costume. And 33 years later at a palace ball, the king appeared seated in a Chinese style sedan.

Of Science and Crosses

However, western art and science were introduced to China via missionaries who were more interested in saving souls than spreading knowledge. Hence, they did not get to the common people. It was only in the late-19th-century's major social upheaval and crisis that the Chinese people turned to western science, for the purpose of reviving their country.