The Imperial Examination System and its vagaries

|

|

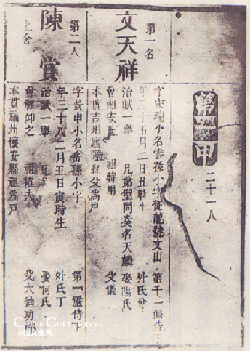

The imperial exam system may be defined as fair play in a man’s world. It was open to all men of letters – in the gender sense – and carried no restrictions as regards to age or family background. Scores were the sole criterion on which contestants were judged. There was also no limit on the number of attempts at each level of the exam. During the 1,300 years the system was in force it was not uncommon to see the names of young adults, octogenarians and even nonagenarians on lists of juren. In 1775, the 40th year of the Qianlong reign, for example, the names of one nonagenarian, 20 octogenarians and five septuagenarians appeared on the lists of juren from around the country. The imperial examinations, therefore, offered an impartial route to social mobility for everyday citizens.

The exam’s emphasis was on liberal arts. In the Tang Dynasty, for example, examinees were well advised to produce examples of their poetry prior to taking the exam. This enabled an assessment not only of their literary grace, but also of their calligraphy. In the practice known as scrolling, examinees would copy their literary works on to scrolls and present them to political, cultural and social personages, in hopes of recommendations to the Board of Rites.

The imperial examination really played an important role in the feudal times in China. By this way the talents were found and selected by the emperors to serve the feudal government. At the same time the contents of the examination was so dull which restricted the thoughts of intellectuals. The imperial examination had a great influence on Chinese people. It inspired the people to study hard to attend the examination and achieve their pursuits. Even today Chinese people still value education and examination.

As the imperial exams focused almost exclusively on Confucian classics, they helped popularize Confucian education and establish Confucianism as one of China’s three pillars of wisdom.

Decline

|

|

It was in the 14th century during the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) that the imperial exams changed format and adopted the Eight Part Essay writing. Gu Yanwu, a celebrated Qing Dynasty scholar, declared the Eight Part Essay practice as “more disastrous than ‘book burning’” (the purge of Confucianism ordered by Qin Shihuang, first emperor of the Qin Dynasty, when Confucian books were burnt and Confucian scholars buried alive).

The Qing Dynasty’s decline matched the deterioration of the imperial exam system. By the late 19th century, the system’s failure to produce competent officials was being cited as the cause of successive domestic and diplomatic crises. Officials began sending imperial memorials to the throne, imploring it to “abandon the imperial exam system and operate modern schools instead.” The Qing Government issued a decree in 1905 announcing the suspension of imperial exams. This marked the end of the 1,300-year-old system. The 1911 Revolution ended the Qing Dynasty six years later.

The merits and demerits of the keju system, however, remained an historical topic. Sun Yat-sen, father of China’s democratic revolution, spoke of the keju (in his Five-Power Constitution) as “the best ancient system for the selection of talented people in the world.” Western scholars commend the keju system as the “fifth invention of ancient China,” in addition to the compass, gunpowder, papermaking and printing. The positive role that the keju system played in China’s history is clearly evident in its literary treasures, as well as in the legacies of its masters of statecraft and military strategy.