The letter of the law

By Wang Jiaquan/Sun Li ( China Daily ) Updated: 2009-03-18 09:30:58

It often appears in beverage ads touting the drink's vitamin contents. It can also be seen in the logo of the state broadcaster, China Central Television.

But when it comes to a name, the letter "C", it seems, is a no-no.

A young man in East China's Jiangxi province, who became a minor celebrity thanks to his unique name, became nameless overnight when he agreed in court on Feb 26 that he would no longer be a "C".

College student Zhao C hit the headlines last June when he won a lawsuit against the local police bureau in Yuehu district, in the city of Yingtan, which refused to issue him a new ID card but asked him to change his name instead. He was told the computer had been thrown off by the presence of an English letter, rendering the registration technically impossible.

C's case was even listed as one of 2008's top 10 lawsuits in China. The list is a compilation of those cases that are believed to be able to pioneer changes in legislation, justice and policy making. It was begun in 2005 and is sponsored in turn by newspapers, law societies and prestigious law schools, including those at Peking University and Tsinghua University.

The public security bureau appealed the court ruling on behalf of the police but a compromose was reached before the new hearing - the appeal was withdrawn, C agreed to change his name and the lower court agreed to cancel its first ruling.

That may have closed the lid on the year-long case but the controversy it triggered has hardly died down.

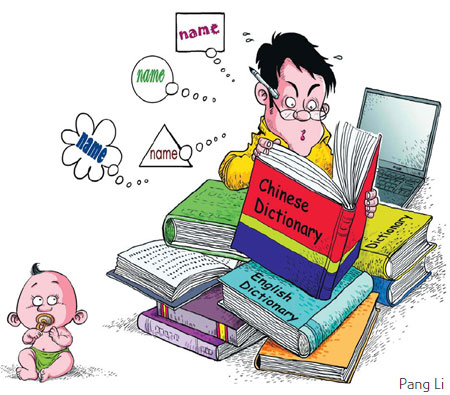

Names usually reflect parents' expectations of their offspring. The letter C meant many things to Zhao Zhirong when he decided to give a name to his son, 23 years ago.

"The combination of the Chinese character Zhao and the English letter C reflected my hope that my son would have a command of at least two languages when he grew up," says the father, who was born to a farmer's family and learned traditional Chinese medicine but eventually became a lawyer.

"C" is also the first letter of the English word "China", and reads like the word "the West" in Chinese, and so the father also hoped that Zhao would one day study abroad but keep his Chinese roots.

"The name was supported by my entire family. Even my grandparents raised no objections," says Zhao snr.

Zhao C faced no difficulty when he went for his first ID card, which was hand-written. Trouble arose when he applied for the new chip-carrying card in 2006. So, the father, on behalf of C, took the police bureau to court in January 2008.

The case came under the spotlight and drew much criticism after it was reported in the media. An online poll at people.com last June showed that 23 percent of about 45,000 respondents voted against such a name, while 31.5 percent expressed their support, saying it was a personal matter.

"Choice of one's name is a civil right. There's no reason to ban it so arbitrarily," said a netizen at Zibo, Shandong province at 163.com, which saw more than 3,200 postings on this issue.

Critics voiced their worries about the erosion of traditional Chinese culture when names began sounding weird or too Westernized. A name such as Zhao C violated the law on the use of standard spoken and written Chinese, they warned.

While agreeing that personal rights should be respected, an online critic named "ebwei" argued at a forum of tiexue.net that a name, instead of only serving as a symbol of personal identification, should in a broader sense act as a carrier of culture.

"But names in recent years are degenerating into sham individuality," said "ebwei".

To linguist Zhang Shuyan of the research institute of language use under the Ministry of Education, a name is more than a personal symbol.

"A person belongs to society and so his name should be closely linked to the culture of the nation he belongs to. A name in a person's mother tongue reflects his attachment to his culture," Zhang says. "I'm not in favor of using an English letter in a name."

Researchers on names, like Hu Xiaomei and Xu Zhisuo, also believe they should serve as carriers of culture. In an article titled The Cultural Contents of Chinese Names , Hu and Xu said names act as tools for recording and communicating one's culture.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Raymond Zhou:

Raymond Zhou: Pauline D Loh:

Pauline D Loh: Hot Pot

Hot Pot Eco China

Eco China China Dream

China Dream China Face

China Face