Look beyond the spitting,shoving and find kind folks

By Xiao Hao ( China Daily ) Updated: 2009-07-09 11:01:01A few nights ago a friend and I rode in a crowded elevator to have dinner together. When the door opened on the top floor, my friend instinctively stepped out first, brushing past a middle-aged Caucasian woman on the way.

There was a brief pause and the woman sneered: "Polite."

I hesitated for a beat. Should I tell her to wipe off her sarcastic superiority, and take it or leave it? This is what China is like - people don't necessarily follow Western norms of decorum; but deep down, like my friend who is ignorant of proper elevator-exit etiquette, they are nice - in a very Chinese way.

Then I realized that five years ago, when I first moved back to China, I would probably have mouthed a condescending "polite" as well. Back then, after a 12-year absence, I was both repulsed and fascinated by people spitting in the streets, shoving at bus stops, and talking loudly in public. I was like a foreigner in my own country.

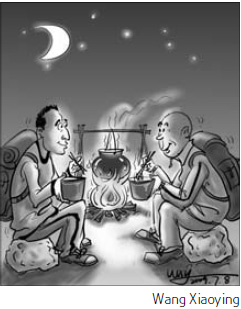

On a month-long trip along the ancient Silk Road from Xi'an to Kashgar, I met Old Wang in the sleeper car to Urumqi. When he found out that I was traveling by myself, he asked if I'd like to join his group for a backpacking trip to Yili. I said hell, yeah.

In Urumqi, Old Wang found me a military backpack and a sleeping bag. He stuffed the tent and the cans of food in his own backpack. "You should carry a lighter load," he said.

I had never backpacked before.

Old Wang was in his early 50s, I think. A bureaucrat in the Xinjiang government, he had a chubby face and a bald head. With his daughter heading off to university and his wife a busy doctor, Old Wang had taken to backpacking in the Xinjiang wilderness with a group of friends.

He had typical Chinese manners - spitting on the sidewalk and arguing loquaciously for pennies in the grocery market. Yet, from the moment we met, he treated me like a son - preparing for everything needed for the trip and carrying my share of the load.

When the hired coach reached Lake Sailimu after an 18-hour bumpy ride, my upset stomach turned into a nastier lower bowel movement. So from the moment we started the hike, he was constantly by my side. "How's your stomach?" he would ask. "Should we take a little break?"

During stops for meals, he would light the gas stove and cook instant noodles while I rushed behind the bushes. Then he would carry the noodles to me, a diarrhea pill right next to the paper bowl. When we reached the camping ground, he set up the tent all by himself. After dinner, as the sun set and the stars rushed out of the blue velvet of a sky, I'd sit with the group and watch them playing cards, guffawing and joking under the camp light.

We went back to Urumqi after five days. The last day in Urumqi, Old Wang accompanied me to do some shopping. He was quiet most of the time. At the end of the day, he asked me to visit him again, in his uncouth, loud and endearing way.

During the past five years, I have grown used to the littering and the chaos in the cities; I have become desensitized to the quarrels in the street and the pushing and the shoving. Sometimes the city and the people still get on my nerves; but I have learned to breathe in deeply, whenever that happens, and remind myself that beneath the uncivil surface, some, or many, of the people in the street are capable of genuine kindness like Old Wang, which is a lot more important than behaving "properly".

Spitting of course is different - it's just not sanitary.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Raymond Zhou:

Raymond Zhou: Pauline D Loh:

Pauline D Loh: Hot Pot

Hot Pot Eco China

Eco China China Dream

China Dream China Face

China Face