Casting dread out of dreams

By Sarah Kershaw (New York Times)

Updated: 2010-08-02 10:18

|

Large Medium Small |

Albuquerque, New Mexico

Her car is racing at a terrifying speed through the streets of a large city, and something gruesome, something with giant eyeballs is chasing her, closing in fast.

It was a dream, of course, and after Emily Gurule, a 50-year-old high school teacher, related it to Dr. Barry Krakow, he did not ask her to unpack its symbolism. He simply told her to think of a new one.

The technique, used while patients are awake is called scripting or dream mastery and is part of imagery rehearsal therapy, which Dr. Krakow helped develop. The therapy is being used to treat a growing number of nightmare sufferers.

In recent years, nightmares have increasingly been viewed as a distinct disorder, and researchers have produced a growing body of empirical evidence that this kind of cognitive therapy can help reduce their frequency and intensity, or even eliminate them.

The treatments are controversial. Some therapists, particularly Jungian analysts, take issue with changing nightmares' content, arguing that dreams send crucial messages to the waking mind.

If a nightmare is eliminated, "you lose an opportunity to really get some meaning out of it," said Jane White-Lewis, a psychology- gist who has taught about dreams at the Carl Jung Institute in New York.

From 4 to 8 percent of adults report experiencing nightmares, perhaps as often as once per week or more, according to sleep researchers. But the rate is as high as 90 percent among groups like combat veterans and rape victims, Dr. Krakow said. He said treatment for post-traumatic stress needed to deal much more actively with nightmares.

Deirdre Barrett, a psychology gist at Harvard Medical School who is an expert on dream incubation, inducing dreams to resolve conflicts, and on the connection between trauma and dreams - said she was struck by the growing interest in nightmares as a result of war trauma and torture.

"Within the community of psychologists who have put an emphasis on dreams it used to be about interpretation," she said. "And now therapists are getting the message that you can influence dreams, ask dreams about particular is- sues and change nightmares."

And Hollywood has just produced its own spin on the idea of controlling dreams, with the release this summer of "Inception," a thriller whose plot swirls through the darkest layers of the dream world. Underlaying the story is the concept of lucid dreaming, another technique used by clinicians to help patients afraid of their dreams understand that they are dreaming while a dream is in progress.

Dr. Barrett supports the use of Dr. Krakow's technique, although she said that ideally the nightmare work should be integrated with psychiatry and behavioral therapies to treat the underlying condition.

Still, Dr. Barrett said, "Barry has made a huge contribution by getting the numbers, getting the statistics and getting the proof that it can work."

Dr. Krakow's nightmare therapy typically includes four sessions of group treatment and between one and ten individual sessions, though Dr. Krakow said between three and five sessions are usually effective.

Patients participate in sleep studies as needed, and do considerable work on their own, using a manual he published to guide them, "Turning Nightmares Into Dreams."

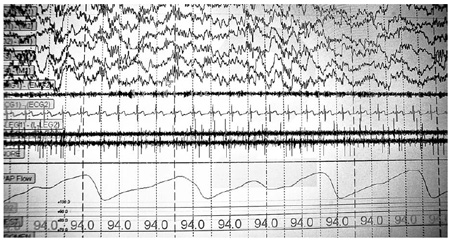

Dr. Krakow's latest research found a striking connection between posttraumatic stress disorders and a variety of sleep disorders. In an analysis of the sleep studies conducted on more than a thousand patients with varying degrees of post-traumatic stress, he found that 5 to 10 other sleep problems may be involved. High rates of sleep apnea, for example, were found even in patients with moderate symptoms of post-traumatic stress.

"In the world of P.T.S.D. and sleep, no one is making these connections," Dr. Krakow said.

His clinic has four small bed- rooms. Before bed, the technicians place sensors on the patients to track sleep, breathing and movement.

Along with other researchers, Dr. Krakow has continued to publish further studies on imagery rehearsal, finding that of hundreds of patients treated, about 70 percent have reported significant improvements in nightmare frequency after regularly using the treatment for two to four weeks.

Roberta Barker, 55, was one of Dr. Krakow's first patients. Ms. Barker says she was kidnapped in Japan, where she had gone to teach English, and was raped and tortured for three days before escaping. Her nightmares, replaying the horror over and over, were so frightening she could barely sleep. Medications did not seem to work. She was on the verge of suicide.

When Dr. Krakow told her that nightmares can be a learned behavior and that she had the power to stop what had essentially become a habit, she was highly skeptical. He explained that she could come up with another dream and practice it and that it was possible for her to no longer have the nightmares of the kidnapping and rape.

"No, it's too easy," she recalled telling him. "It can't work."

Some patients work to change the plot of their dreams; a rape victim who was receiving treatment with Ms. Barker decided to script a dream about confronting her rapist with a baseball bat. But Ms. Barker said she felt she had to come up with an entirely new dream. So she chose birds.

"I've always loved birds, wild birds, doves and pigeons and starlings, mountain blue jays," she said. "I had fed birds, the images were solid, I could hear them flying and talking. Now, instead of waking up screaming, I wake up knowing I've dreamed of birds."