Lost in translation

|

|

To do or not to do,that is a question. |

Another sobering fact is that one can get only 50-60 yuan by translating 1000 words in literary works, but a comfortable 300 yuan in business translation.

The translators have been the leading edge in this communication and they are insisting on better treatment. Many people have bowed out of this profession when they eventually found themselves economically challenged as a professional literary translator.

More telling is the situation in the schools. The Beijing Foreign Studies University is one of the leading schools in training translation professionals, but almost all of its students choose business translation, rather than literary translation, as their careers.

A survey conducted by the newspaper People’s Daily in 2009 shows that among the 37 students involved, only 32.4% showed any interest in literary translation. Considering the qualification and the huge gap of payment between literary translation and business translation, 94.3% expressed their hope of being a translator in the business circle.

“To be a literary translator is not enough to feed myself,” said Zhang Cong, one of the respondents.

“I just take it (literary translation) as my personal interest. The desired job is business translator,” another student, Jin Yan, said.

This is a sad comment on the social status accorded to literary translators. It may also explain why credible literary translators are still few and far between in today’s China.

A report by the Translators Association of China (TAC), the only national association in the field of translation in China, shows that there are 60,000 registered professional translators employed in China, but they have to deal with over 30,000 foreign books introduced every year, not to mention those in the public domain. Despite their genuine efforts, they still lag behind the growing market demands.

With the arrival of the Information Age, ardent devotees of translation are allowed to break new ground in the computer-based virtual world. Their ability and speed never cease to surprise the world’s readers. On July 21, 2007, Harry Potter 7 was officially released in Britain. Two days later, the Chinese version of this bestseller appeared on the Internet, thanks to the joint efforts of 60 enthusiasts.

|

|

The vast Chinese market still beckons. |

|

|

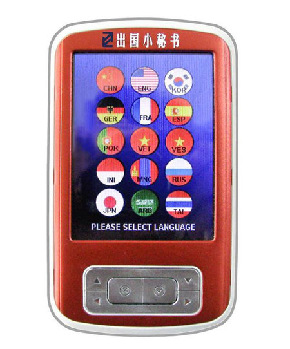

Will this little gadget help us out? |

For many young Chinese people, popular foreign magazines and books are among their favorite things to read. The Economist, a renowned economic magazine, is now translated by a team of freelance translators. They publish the Chinese version of the contents every two weeks on the Internet, just for free reading.

As they often have to race against time,many mistakes emerge in their hurried job. But these people present a rising force that may form the backbone of Chinese translators in the years to come.

Thankfully, some established foreign publishers, led by Penguin Group and Random House, have begun to direct their attention to the vast Chinese market and make their business presence felt here. With their help, books written by prestigious Chinese writers, such as Lu Xun, Zhang Ailing and Qiang Wenzhou, are given a chance to enter the global market and reach more readers.

This movement, however, also sets an alarm bell ringing. Considering that Chinese writers are usually slow to enter copyright trading in the global market, professional agents are needed to inform them of the global practices, the latest trends in foreign markets and launch promotion campaigns accordingly.

Economic globalization also acts as a stimulus in China’s ambitious campaign to promote its culture. With China’s robust economic performance, foreigners are becoming ever-more eager to understand China, as can be seen in the steadily growing number of Chinese books translated into foreign languages. In addition, more foreign readers are beginning to lift their eyes up toward Chinese literary works.

This sets the stage for Chinese literature to go global, but also presses us to move forward with a sense of urgency. This is the viewpoint of Huang Youyi, vice president of TAC.

In the year 2004, the News Office of the State Council of China and the General Administration of Press and Publication launched China Book International, a program to promote the translation and publication of Chinese works overseas. The campaign, designed to make Chinese publications “go global” in a more efficient manner, issues an annual Recommended Bibliography for China Book International, and introduces books to publishers at home and abroad by means of book fairs, mass media, websites and magazines.

Admittedly, it requires cooperation from all walks of life to see any movement in the campaign. Despite all these lingering problems, Chinese literature, slowly but surely, will reach the rest of the world if we give a serious answer to the question: HOW?