A German and Muslim finds fame is complex

By Michael Slackman (China Daily)

Updated: 2010-10-24 16:47

|

Large Medium Small |

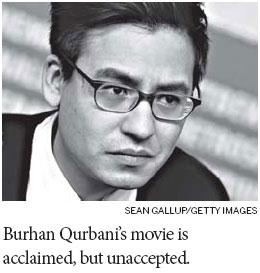

BERLIN - It has been many years since a German film student had a feature-length movie shown at the prestigious Berlinale International Film Festival, a distinction that can launch a career. That is what Burhan Qurbani is enjoying at the moment, with his film "Shahada."

But rising fame can be double-edged. Mr. Qurbani, 29, suddenly realizes that he is a foreigner at home, and that his audience sees him as an Afghan immigrant who made a movie about Islam, not as a talented German filmmaker exploring issues common to all mankind. "I'm seen as the Afghani who made the film about integration, and that hurts a little," he said.

The film's characters, three young Muslims living in Berlin, confront issues like forbidden love and guilt. They seek refuge, and redemption, in religion. But context is what ultimately defines, and that is largely true with this film, which was produced in 2009 but released this year amid a heated public debate over integration and rising anti-Islamic sentiment.

"Of course, I am German," Mr. Qurbani said. "I have Afghani roots, I can't deny that, but mostly, I am German."

Mr. Qurbani's personal narrative should be a tale of immigrant success. His parents fled the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan and settled in Germany. His father was an electrician, but his parents divorced, so his mother raised two boys with the help of public assistance. He received a first-rate education and had the chance to pursue his dream of becoming a filmmaker.

"Shahada," his student thesis, was screened at the Berlinale festival in February, and was shown recently in theaters in Berlin. This month, the Chicago International Film Festival named Mr. Qurbani best new director.

While Mr. Qurbani appreciates the reception that his film has gotten, its timing has cast him as a symbol of the fragile fault line currently challenging societal cohesion in Germany.

"It is tragic what is happening here,'' said Hatice Akyun, a writer and lifelong German resident of Turkish descent.

After living here for 40 years, she said, she is so distraught by what is happening that she is considering moving to Istanbul. "The only country I consider home," she said, "is Germany. But it is getting worse and worse."

Mr. Qurbani said that although he has assimilated, he is acutely aware that he is looked on as an outsider.

"My grandfather told me and my brother, 'You are like a bird without legs; you cannot land,'" he recalled. "You will never be at home here and you will never be at home in Afghanistan."

He now realizes his grandfather was right. "I'm not the filmmaker who worked with brilliant actors and a talented cinematographer; I'm the Afghani," he said.

Like much of Europe, Germany is gripped by anger and mistrust between ethnic nationals and immigrants,. The long simmering debate in Germany, broke into the open with a recent book that condemned Muslims for "dumbing down" society. The book warned Germans they were losing their country.

Mr. Qurbani named his film "Shahada" because it is the Muslim declaration of faith. And his characters were Muslim, but that, he said, was where it ended.

"The purpose was to make a film that didn't exclude people, but that invites people to find the answers and ask the questions about conflicts that we are all struggling with," he said.

The New York Times