Outside the expat bubble

|

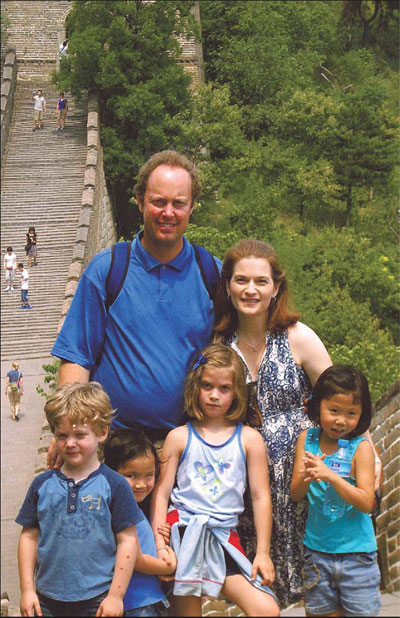

Ralph and Melinda Howe with children (from left) Jonah, Abby, Riley and Amanda on the Great Wall. Provided to China Daily |

Those who live in China without an 'expat package' of financial assistance are facing some pretty daunting costs for a family. Tiffany Tan reports

Ralph and Melinda Howe took a combined $20,000 pay cut to move their family from Orlando, Florida, to Beijing, in March. Two of their four young children were adopted from China, so the couple decided it was important for the family to spend at least three years here to better understand the country. "We want all four of our kids to learn the language - and us if we are capable - and for all of us to experience, at least in part, what it is like to be from Asia," Melinda, 42, says.

"Our girls who were born here will know that we feel like their native culture is important for all of us to embrace."

But raising a foreign family in China comes with a huge price tag. The cost can become a burden, especially to people who are not on an "expat package": financial assistance provided by companies to overseas hires, usually in the form of free housing, coverage of children's tuition at international schools, medical insurance at Western hospitals and yearly round-trip tickets home.

Ralph Howe, 45, a former professional golfer who once played in The Masters, is now head instructor at Anselmo Golf Academy in Shunyi district. Most weeks he works six days, one day more than he did back home.

Meanwhile, Melinda homeschools their daughters, aged 8, 6 and 4, and their 5-year-old son. International schools, which can charge primary-school students up to 180,000 yuan ($27,000) a year, are too expensive for the Howes - although they think they would be ideal.

The couple did consider the more affordable Chinese schools, but in the end thought a foreign curriculum in a foreign language would be too much for the children to handle.

"To put them into that and have them be graded when they don't understand anything would actually be counterproductive," Melinda says. "We were already uprooting them and our oldest daughter was not happy that we were moving."

With the family renting a villa in Shunyi, chosen partly for its backyard playground for the children, Melinda knows they are already "living like kings" compared to the majority of the Chinese population. But the Howes have cut back on other expenses, such as imported food. For instance, US breakfast cereal, which costs around 60 yuan a box, is off the menu no matter how much everyone craves it.

"That's not even an option. Four kids will eat a box in a day," Melinda says. "If we buy it, we buy the brands that are made in China, like Cheerios, but they don't taste the same. On the top of my list for when I go home is eating Cheerios that taste like Cheerios," she says with a laugh.

The Howes consider annual trips back to the United States to see relatives a necessity, although these set them back at least $10,000 a year in plane tickets and accommodation costs. The amount represents their biggest expenditure in living overseas.

"It's money that we could be putting into retirement or we could be putting into the kids' education or something else, but it's gotta get burned up in plane tickets," Ralph says. "If we had a package from a company, we would have that covered."

For David and Prudence Sinkala, Zambian nationals who have been living in Beijing for a decade, housing is the biggest headache. David works for a Western embassy (he is not allowed to say which because of policy), while Prudence is with the Zambian Embassy. They put a big chunk of their monthly income into a 6,000 yuan ($900) apartment outside the East Fourth Ring Road and are having to cope with the instability of living in a rented home. Since 2008, they've had to move three times.

"The house prices were going up and so people were selling their houses," says Prudence, 33.

The cost of their children's education is another major challenge. They spend 3,000 yuan a month to send their eldest, a fifth grader, to the Pakistani Embassy College, considered the lowest-priced, English-language school in town. English is the main language of instruction in Zambia and the couple want a smooth academic transition for their three children should the family decide to move back to Africa.

For their 3-year-old second child, the couple is trying out a bilingual school, which also charges 3,000 yuan a month. But they are not satisfied with the results so far.

"They say they are bilingual and that they are teaching the child in English, but whatever comes home as homework is all in Chinese," says David, 39. "It's very difficult for us to monitor if they are really teaching them in English."

For medical bills - another basic expense - "we pay as we go", since Chinese hospitals now offer the same treatment to both local and foreign patients, says Prudence.

"When we first came, it was more difficult because most hospitals couldn't attend to foreigners," she says. "There were just specific hospitals they would call them foreign wing where you would pay maybe five, 10 times more than the locals for a similar treatment."

Meanwhile, as a treat every quarter, the Sinkalas allow their children to indulge in their favorite restaurant or leisure park, or take them shopping. But there are some months, says Prudence, when money is tight and she has to say no to the kids no matter how much it pains her.

"Sometimes it's hard, when bills come at the same time," she says. "You pay for her school, for his school, for rental, for water, for the driver, for the ayi (helper)."

The Arringtons, another American family not on an expat package, have adjusted pretty easily to life in Beijing. This, they say, is primarily the result of spending their first four years in China living in Tai'an, a prefecture-level city in Shandong province. They moved to the Chinese capital only five months ago.

"I can get coffee here, pizza, just the little things that you miss from home," says Chris Arrington, 50, an English teacher at Renmin University of China. "Sometimes maybe you want a steak or sometimes you want a hotdog and it just isn't available (in Tai'an)."

"There wasn't an international school, there wasn't an international hospital," adds his wife Aminta, 40, also an English teacher at Renmin. "When our kids got sick, and they did, we went to the local hospital. Not because we didn't have an expat package, but because it was the only hospital there was."

Their three children, two biological and one adopted from China, go to a Chinese elementary school, where they pay 6,000 yuan a year for each child. In the evening, Aminta supplements their Chinese education with lessons in English reading and writing. Like the Howes, the Arringtons came to China to better understand the native culture of their adopted child.

Chris and Aminta, who come from Washington state, aren't worried their children will have difficulty adjusting to the US system of education once their time in China is up. "They'll be going from something hard and challenging, in a language that is not their own, to an easier, more fun system in their mother language," Aminta says.

"I've never heard the term expat package, actually, until the last few weeks. 'Expat package, what's that?'" she says.

(China Daily 01/04/2011 page18)