Screenagers pathologically addicted or preoccupied?

|

|

A new study appears to show that one in 10 Singapore school children are addicted to gaming and that is affecting their mental health.

There might be trouble brewing behind the glassy eyes of kids who spend too much time and energy on video games, according to a controversial new study.

In the two-year study of more than 3,000 school children in Singapore, researchers found nearly one in 10 were video game "addicts", and most were stuck with the problem.

While these kids were more likely to have behavioral problems to begin with, excessive gaming appeared to cause additional mental woes.

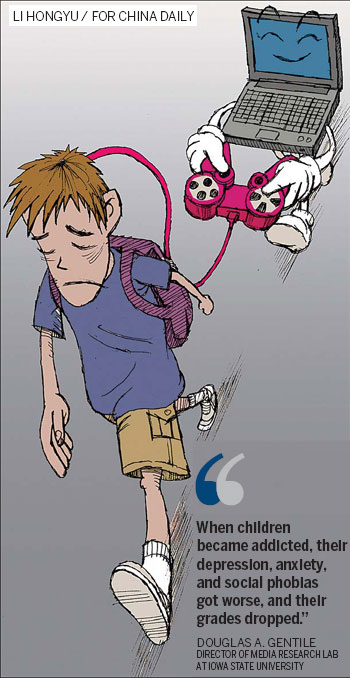

"When children became addicted, their depression, anxiety, and social phobias got worse, and their grades dropped," says Douglas A. Gentile, who runs the Media Research Lab at Iowa State University in Ames and worked on the study.

"When they stopped being addicted, their depression, anxiety, and social phobias got better."

He says neither parents nor healthcare providers are paying enough attention to video games' effect on mental health.

"We tend to approach it as 'just' entertainment, or just a game, and forget that entertainment still affects us," he says. "In fact, if it doesn't affect us, we call it boring."

But an independent expert said the study had important flaws.

"My own research has shown that excessive video game play is not necessarily addictive and that many video gamers can play for long periods without there being any negative detrimental effects," says Mark Griffiths, director of the International Gaming Research Unit at Nottingham Trent University in the United Kingdom.

"If 9 percent of children were genuinely addicted to video games there would be video game addiction clinics in every major city," he says, adding that the concept is not currently an accepted diagnosis among psychiatrists and psychologists.

Part of the problem, Griffiths argues, is that the new work may be measuring preoccupation instead of addiction.

In the study, teachers handed out questionnaires to students in the third, fourth, seventh and eighth grades, including questions about their gaming habits, social skills, school performance and depression.

The kids also answered 10 questions to find out if they were addicted to gaming - so-called "pathological" gamers. If they answered half in the positive, they got the label.

The questions included things like having neglected household chores to spend more time on video games, doing poorly on a school assignment or test as a result, or playing video games to escape from problems or bad feelings.

On average, the kids said they played about 20 hours a week. Between 9 and 12 percent of boys qualified as addicted in this study, compared to 3 to 5 percent of girls.

Of those children who started out as addicts, more than eight in 10 remained so during the study. "It's not simply a short-term problem for most children," Gentile says.

While the researchers didn't put a number on how many youngsters had mental problems, they did find that those who played longer hours, were more impulsive or had poorer social skills and were at higher risk of getting addicted over the two-year period.

Those who did become addicted reported increasing symptoms of depression, anxiety and social phobia. Gentile says it appeared that unhealthy gaming habits were fueling the kids' mental problems, which in turn might cause them to up their screen time and so forth.

But he acknowledges his research didn't prove that point.

In an earlier US study, he found that children who watched a lot of TV or played a lot of video games had slightly more problems concentrating on school work. However, that study couldn't prove that screen time was at the root of the narrowing attention span, either.

The American Academy of Pediatrics, which published the new study in its journal Pediatrics, recommends limiting children's time in front of computers or TVs to two hours daily.

"One thing we have to bear in mind is that children playing video games for two to three hours a day is normal. It has displaced activities like watching TV," Griffiths says.

Still, he says, a small minority of kids probably does suffer from true video game addiction, just as some people are pathological gamblers.

In general, Griffiths advises that parents try to give their kids educational games instead of violent ones, encourage playing in groups, and follow the directions from the manufacturers, such as sitting at least 60 cm from the screen and not playing when feeling tired.

"I have three kids, all of whom are the archetypal 'screenagers' who spend a lot of time a day interacting with technology," Griffiths. "Basically, even when playing a couple of hours most days it is not impinging negatively on their lives."

Reuters

(China Daily 01/19/2011 page19)