A life etched in lines

|

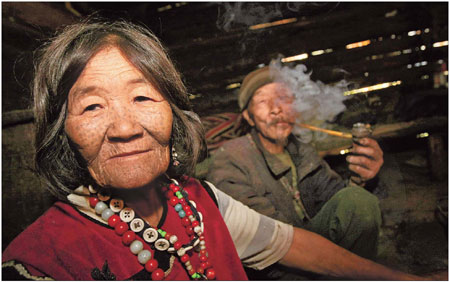

Bing Xiufang, 75, with her husband, at their house in Gongshan county, Yunnan province. Even after so many years, the tattooed patterns on her face are still visible. Photos by Chen Yuzhou / for China Daily |

|

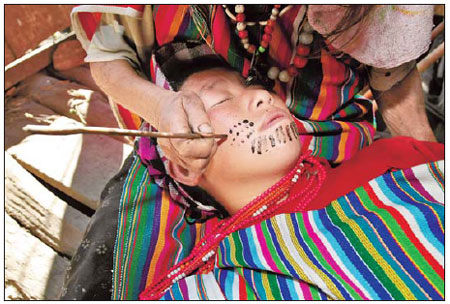

During a demonstratiosharpened bamboo sprig.n for tourists, a tattoo artist carves patterns into a girl's face with a sharpened bamboo sprig. |

|

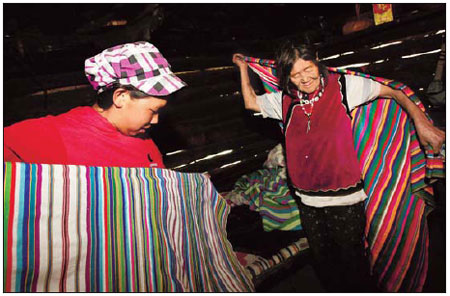

Getting the tattoos was a rite of passage for Derung women, and they had to dress up for the ceremony. |

|

Geng Kaifang, 79, is one of the 48 surviving face-tattooed Derung women in Gongshan, a custom that stopped in 1949. |

The custom of tattooing faces among Derung women is fading as modernization washes over their lives. Cheng Anqi reports.

The ethnic Derung face-tattooing tradition is dying out along with the last of the women who bear this mark of tradition in Gongshan county, Yunnan province. This reality has long been known, but it has won renewed attention since November's sixth national population census determined there are only 48 tattoo-faced women left. The oldest is more than 100 years old and the youngest is 50, the survey found.

The township was one of the country's last to be connected to the outside world by highway. Since the road was completed in 1999, the area has become an adventure tourism destination, attracting travelers hoping to see the last of these women before it's too late.

The highway has made 75-year-old Bing Xiufang the country's most visited face-tattooed woman, as it runs in front of her house. Bing's cousin was a tattoo artist when she was young, so she's intimately familiar with the process that goes into creating the markings.

"In the Dulong River valley girls aged 12 or 13 would get the tattoos as a rite of passage," Bing says.

"But in olden times, it was an extremely painful way to fend off defloration by outsiders."

The practice began about 300 years ago, when Tibet's landlords extended their power into the Dulong region and cruelly exploited the people living there.

They levied taxes on the area's inhabitants. If a household couldn't pay up, the landlords would take women in lieu of money for use as slaves or child brides. Beautiful young girls were at particular risk of being enslaved.

So, Derung women started tattooing their faces to make them look like ghosts and, consequently, undesirable to the landlords.

They retained the practice until New China's founding in 1949.

The tattooing process began with a girl washing her face and lying on the ground. A tattoo artist would then carve patterns into her flesh with a sharpened bamboo sprig and rub coal ash from the base of a cooking pot into the wounds.

A week later, the scab would fall off, revealing a permanent cyan blue pattern.

No Derung woman has been willing to undergo this painful old ritual in the new society since the ethnic group gave up its communal existence after 1949.

Bing remains in good health for her age. She still labors in the fields and does part-time work demonstrating the tattooing process for tourists.

Face tattoos are different in the Dulong's upper and lower reaches.

Customarily, patterns drawn in the upper reaches begin in the forehead and cover the entire face.

Those in the lower reaches are painted on the lower jaw and throat like a beard. Only four women with partial markings are still alive, the survey found.

And only one partially tattooed woman still lives in the Dulong's lower reaches - 96-year-old Bapo village native Wang Caidai.

Wang moved to Gongshan county town in 1996 to live with her son, leaving the public to believe Bapo's last face-tattooed woman had died.

She was discovered in November, 2010, by a team of experts and officials who traveled to the township to conduct a survey of face-tattooed Derung.

Four faint vertical lines snake across the bottom of Wang's jaw.

"I was supposed to get a full face tattoo, but I was too afraid and it hurt too much. I cried so hard," she says.

"The tattoo artist was delicate, so the marks aren't so dark."

Wang's tattoos certainly are different from those of 86-year-old Mu Wenxin.

The elderly woman moved with her entire family from the river's middle reaches to Bingzhongluo township's Shuangla village, about 20 km from Gongshan, where she lived in her 20s.

The village, located on a mountaintop more than 2,000 meters above sea level, became a Derung relocation settlement in the 1960s.

Today, 36 of Shuangla's 42 families - accounting for 114 people - belong to the ethnic group.

Mu's tattoos are typical bluish-black patterns that start at her scalp and dribble down the bridge of her nose and around her eyes before stretching across her cheeks and throat. Her lips and the tip of her nose are completely colored in.

The pattern resembles a butterfly with its wings spread in flight.

Mu says she never felt different from others until a recent trip to the national capital.

"When I visited Beijing last November, people stared at us, and everyone asked if they could pose with us for photos," she says.

(China Daily 01/31/2011 page22)