Crossing the musical rubicon

|

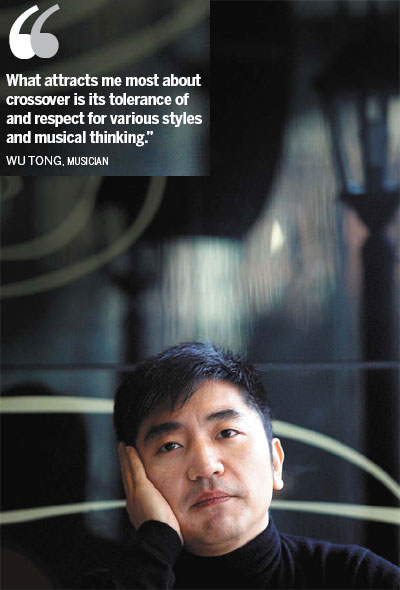

Wu Tong rediscovers traditional Chinese music after working for years with musicians from diff erent cultures. Zhang Wei / China Daily |

Rock singer Wu Tong says mixing musical styles is not only creative, it also shows that people can live together harmoniously. Mu Qian reports.

Rock singer and sheng (Chinese mouth organ) player, Wu Tong continues to show his versatility, this time with his solo CD The Sound from My Heart, which he defines as a crossover album. This album "contains honest and organic music that has no label or boundary", announces the CD cover introduction.

It employs a variety of instruments from around the world, including the xun (Chinese ocarina), guqin (Chinese plucked instrument), guitar, cello and Indian tabla (drums). The works include Wu's compositions, a piece of Northern China's narrative music, and folk songs from around China.

"What attracts me most about crossover is its tolerance of and respect for various styles and musical thinking. Although people from different areas have different styles, the ultimate thing we want to express is the same," says Wu, who sings vocals and plays the blown instruments. "Crossover music is the simplest way to tell different peoples that we can live harmoniously together."

In Watching for the Spring Wind, a song from Taiwan, Bach's Cello Suite No 1 in G is seamlessly woven with the sheng's harmony, while Wu sings in a Taiwan dialect.

The track Linglong Tower was Wu's most popular piece when he performed in Tianjin, a city with a long tradition of quyi or narrative music. Wu fused this light-hearted tongue twister with rhythm and blues.

When Wu performed in the United States, he improvised Jimi Hendrix's songs on his sheng. Although improvisation seems to be something unusual when playing the sheng, Wu says Chinese folk music is full of possibilities.

"Whatever music I play, it'll always be about being Chinese and expressing life experiences," Wu says.

Born into a family of blown instrument manufacturers and players, Wu started studying sheng when he was 5.

It was not his choice, and he didn't find the instrument interesting until he was 11, when he had his first experience of improvisation with sheng, which for him felt like an adventure.

In 1990, Wu was enrolled at the Central Conservatory of Music as a sheng student, but spent most of his time on Again, a rock band that he formed with some friends.

Again was one of the first bands to blend rock music with Chinese idioms. The band not only used Chinese instruments, such as pipa (lute), but also tuned their guitars according to traditional Chinese scales. They also used ancient Chinese poetry as lyrics.

"At that time I was keen about breaking the stereotype of Chinese music's mild temperament, and rock 'n' roll provided me very valuable experience," he says.

Wu released four albums with Again, but he gradually found that rock restricted his music ideas. He was looking for something more open.

An opportunity came for him to explore a different way in 2000 when he was invited to participate in cellist Yo-Yo Ma's Silk Road Ensemble. Initiated by Ma, this ensemble is a collective of musicians from various countries and regions interested in maintaining their own cultural heritage and at the same time exchanging ideas across ostensibly dissimilar cultures.

Since then Wu has participated in the recording of four albums and many performances of the Silk Road Ensemble, during which time he has met musicians from such diverse traditions as the Mongolian long song, traditional Persian music, and Azerbaijani mugham.

Representing Chinese blown instrument music, Wu's sheng is part of a big family of world instruments in the ensemble that also includes the duduk (Armenian double reed woodwind), shakuhachi (Japanese bamboo flute) and morin khuur (Mongolian horse head fiddle).

This exposure to such diverse music traditions opened a gate for Wu's vision, and called upon him to rediscover the music styles that he listened to as a child, including Chinese operas, narrative music and pop songs.

"The experience of playing in the Silk Road Ensemble led me to break the idea of genre. It's another revolution for me, just like rock music was to me earlier, as something that can break the obstacle between the musicians and audiences," Wu says. "In the Internet age, it's easy to get to know different music traditions, and music is now open to immense possibilities."

In The Sound from My Heart, Wu tries to reinterpret music by "standing above styles". One of the tracks, Snowing, is one of his earliest compositions and dates back to when he was at college, but it has a totally different feel now under his new concept.

A serene atmosphere is created by a guqin, when Wu begins to sing about his inner solitude when walking alone in the snow. The work becomes more lively as a tabla adds a heartbeat-like rhythm, as if a positive mood is gained through philosophical thinking.

Another example of Wu's crossover works is Swallow Song, a traditional Kazak folk song that Wu learned when he traveled in Xinjiang in Northwest China. Accompanied by a cello, the melody of the song becomes even more melancholy.

Wu played a tune titled Kuai Le on the CD Yo-Yo Ma & Friends: Songs of Joy and Peace, which won the 52nd Grammy Awards' Best Classical Crossover Album in 2010. This year, the Silk Road Ensemble's Off the Map, in which Wu participated, was also nominated for the award.

Wu is no longer the lead singer of Again, but he has a new group called Magpie, which plays traditional Chinese music with new arrangements and instruments that include the violin, pipa, guitar and sheng.

"I feel very lucky to be living at a time when a musician is able to get to know so many diverse cultural backgrounds," he says. "The nourishment I get from tradition makes me more confident of creating the future."