Lingua franca

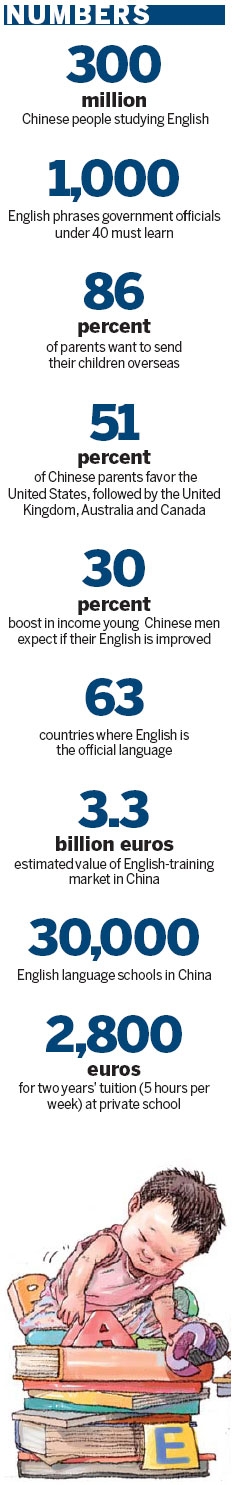

In a survey by one of China's biggest websites, Sina.com, 86 percent of parents said they wanted to send their children overseas. More than 51 percent of Chinese parents favored the United States, followed by the United Kingdom, Australia and Canada.

Only 7 percent of parents wanted to send their children to Japan, Italy, France or other countries to study.

For young urban Chinese, topping up their English skills has become a priority.

Popular website Tencent recently conducted a survey among 3,000 young people and discovered that males learning English believed they could boost their salaries by 30 percent while females believed that speaking English made them appear more fashionable.

There is also the desire for China, which only opened its doors to the West about 30 years ago, to better communicate with the world. English is the official language in 63 countries and is used every day by more than one-third of the world's population.

During President Hu Jintao's recent visit to the US, the Chinese government paid for a promotional movie to run in Times Square, New York, informing telling Americans more about China. It featured many famous Chinese, such as Jackie Chan and Yao Ming, and all were speaking in English.

The demand for English has created major business opportunities and in 2010, the National Education Development Statistical Bulletin and the English-training market reached 30 billion yuan (3.3 billion euros).

Analysts are predicting annual growth across the private English school sector in China of between 12 percent and 15 percent as urban incomes rise.

|

|

The sector is made up of schools and institutes affiliated with universities, foreign-funded groups, domestic private organizations, and countless small- and medium-sized private schools.

China's largest private education provider is New Oriental with 324 learning centers and schools. Since its 2006 debut on the New York stock exchange, its shares have more than quadrupled in value. Investment bank Goldman Sachs, in a recent analyst note, said the group's enrolments continue to rise, ahead of expectations.

Despite the rapid growth in colleges there still is no official data on the overall number of English-training institutes and schools in China, but some put the figure at 30,000 schools teaching English.

Tiger Tao, senior director of United English college in Beijing, estimates there are between 2,000 and 3,000 English-language schools operating in Beijing alone, reflecting the demand for training.

"But some are very small with one teacher, one classroom - they rent a classroom - and just one foreign face," he says, adding more than 10,000 students have passed through his school since it started in 2000.

Tao says 50 percent of his students are aged between 20-30, and most have an English language background.

"About 50 percent having a higher than basic language level, and about 30 percent just a basic level," he says.

"For students who start from the very basic level it takes about five hours a week of lessons for two years to become very proficient, but that's also requires a lot of practice outside the class."

"Language acquisition is a process of learning language and using the language," Tao says. "Unfortunately, a lot of English language teaching in China is not very efficient because students don't get the chance to use it.

"So we encourage students to use the language outside the classroom at our centers. All our employees speak English so even students who don't take the classes can talk with our employees in their spare time."

Tao says the expansion of foreign companies presents special opportunities for Chinese workers with high English language proficiency.

More than 240 of the Fortune 500 companies have set up offices in Beijing and almost all have a presence in China.

"The government is also encouraging big State-owned enterprises, such as energy, oil and metal companies, to expand overseas and as a result, more Chinese staff need English training," he says.

"One energy company has approached us because they are going to start a joint venture with a Middle Eastern company. They would like to train 200 and these employees have to go overseas," Tao says.

"Another company is Huawei, one of the biggest telecommunications equipment producers in China. It has expanded a lot of overseas so suddenly they need a large group of staff who can speak English."

The cost for two years' tuition at United English is about 25,000 yuan (2,800 euros), Tao says.

"Extravagant" is the adjective that most people used after learning that Yao Wanchen, 27, spent 42,000 yuan ($6,200) on a one-and-a-half year English training program just to improve her English.

But Yao does not think so, and neither do countless trainees in many English-training schools and institutes around China. "I think greatly improving my English is well worth the investment. I am in charge of foreign trade for our company and most of my customers are foreigners. Excellent English is very necessary for me," says Yao, an employee from the international trade branch of the China Animal Husbandry Group.

Chen Ming, executive vice-president of EF English First Asia, says millions more Chinese English-language speakers will have a huge impact on China's competitiveness as an economic superpower but she agrees that despite the high numbers of people studying English, the overall standard is poor.

EF English First, which started in Shanghai in 1993 and has taught millions of Chinese students English, was the official language trainer for the Beijing 2008 Olympics.

"One of the biggest challenges for Chinese people, who start to learn from a young age during compulsory schooling is the of lack opportunities to apply their English, and actually use it," Chen says.

"We also have found that many Chinese learners of English do not have a lot of confidence in speaking English."