Tears of joy as junior makes it to primary school

woke up at 5 am in the tranquil city of Iowa in the United States, thinking that thousands of kilometers away, my 6-year-old son was under huge pressure over which primary school he would go to in Beijing, the coming September.

There seemed little hope of him getting into two schools in our neighborhood, as my son didn't get high scores in their entrance exams.

Then the next morning, great news awaited me. The school highest on our wishlist had finally accepted him!

It's hard to describe the bliss that turns joy to tears. I can only compare it with the time I was accepted to university and the time I landed a job.

My husband and I never thought it would be so difficult to find a school that did not burden him with homework and exams.

So we sat back as my son's classmates moved into downtown Beijing, to settle into small apartments close to a famed school. Like in the United States, proximity to a good school is a vital factor in the admissions.

Last December, the headmaster of my son's kindergarten gathered all the parents and announced proudly that none of her students had ever failed a primary school entrance exam.

Could she be serious?

I grew up enduring the pressure of the national college entrance exam, once described as a "single-log bridge" that allowed only the ace of aces to get into university, with its promise of a bright future.

Getting into college is no longer as difficult. However, millions of college graduates from 2010 are still looking for a job.

Ironically, it seems the "single-log bridge" has now become one connecting kindergarten to primary school.

We took our son to a nearby public school, just before I left for a short teaching program in Iowa. Hundreds of anxious families listened to the headmaster, who went on about how good their classes were, but warned that if the children didn't stop making a noise during her dull speech, they would be called to the front of the auditorium.

My 70-year-old mother and I waded through the huge crowd waiting outside the classroom where the children were tested in Chinese characters, pinyin, math and English.

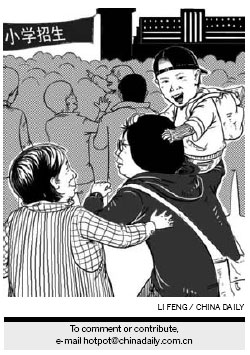

"Mom, I thought really hard, but I still didn't recognize some of the Chinese," my son told me later, as I carried him on my shoulders out of the surging crowd.

"There's little hope of him making it in such a school," I told my family.

The other choice, a private one funded by a Taiwan-based company, had a much more organized admission process. My son walked into five or six classrooms to answer various questions. My husband and I also sat down with a senior teacher from Taiwan. Our son couldn't sit still and didn't immediately say "thank you" when the teacher asked what he should say before each meal.

A week later, we heard that our son was put on the "waiting list". This triggered much panic as we racked our brains for a way out.

Just before my departure, my aged father and I visited the school on a rainy afternoon, pleading with the teacher in charge of admissions and reiterating how we strongly supported their ideals of nurturing a self-respecting, independent, and wholesome human being.

Meanwhile, colleagues had been chipping in with helpful tips, including one well-regarded school near the office. So great is the demand for this school, that many sign up for it as soon as they have a child.

My son was once again placed on the waiting list but even if he had made it, it would have meant moving out of our spacious apartment in the suburbs. It would be a worthy sacrifice, I thought.

Finally, luck smiled on us. Some chosen student had given up his seat at the private school near our home, and my son got in, ending two weeks of much anxiety.