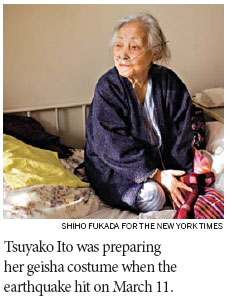

Last geisha difies time and waves

KAMAISHI, Japan - When the earthquake struck at 2:46 p.m. on March 11, this city's last geisha was, fittingly, at home getting ready to sing that night at an 117-year-old ryotei, a type of exclusive restaurant, in Kamaishi where she began working as a 14-year-old seven decades ago.

She had already put on the white split-toe socks she would wear with her kimono and was preparing to put her hair up. Hired to entertain a party of four in honor of a colleague's transfer from Kamaishi, she had picked just the right song, one meant to steel young samurai going to their first battle.

But a tsunami would engulf this city within 35 minutes and the geisha, Tsuyako Ito, 84, fought to survive. She had lived through three tsunamis before in Kamaishi, and as a girl she had listened to her grandmother's tales of the great 1896 tsunami.

"My grandmother said that a tsunami is like a wide-open mouth that swallows everything in its path," Ms. Ito said recently from a local hospital where she was being treated for asthma, "so that victory comes to those who run away as fast as possible."

Her mother carried her on her back to safety at the time of Ms. Ito's first tsunami in 1933. This time, after her legs gave out, an admirer carried Ms. Ito on his back to higher ground.

Ms. Ito, who had planned to retire on her 88th birthday, a milestone in Japan, survived her fourth - and "most frightening" - tsunami. The waves swept away her shamisen, a three-stringed instrument, and kimono, essential to a geisha's art.

A famous beauty, Ms. Ito both danced and played the shamisen, while most geishas were skilled only at playing the shamisen, said Setsuko Kanazawa, whose family owns Saiwairo, the ryotei where she performs. To cultural preservationists here, she is the guardian of a local culture that was fast disappearing.

"I loved to dance," she said. "And I simply wanted to become a leading geisha in Kamaishi."

After a marriage to a sushi restaurant owner, the birth of a daughter and a divorce, Ms. Ito went to Tokyo to study dance. Ms. Ito and a dozen other geishas were constantly on call at the ryoteis, as Kamaishi's economy began booming in the 1950s. Kamaishi is the birthplace of Japan's steel industry. But through the years, business declined and the demand for geishas diminished. Still, sometimes the calls came for Ms. Ito, some from old customers, and more recently from new customers reflecting the world's new economic order.

"Chinese industrialists, among others, now come here," said Satoshi Ito, 63, Ms. Ito's nephew.

On March 11, as Ms. Ito was getting ready to perform, the tsunami assailed Kamaishi, eventually reaching inland to the house where she and her nephew lived. After a wall in her house collapsed and she slowly moved to flee, Hiroyuki Maruki, 59, a sake store owner and the president of a group dedicated to preserving an old melody called "Kamaishi Seashore Song," came by looking for her. "She is the only one who knows how to sing that song," Mr. Maruki said. As Mr. Maruki carried Ms. Ito up a hill, she recalled "feeling the soft warmth of his back."

Having survived yet another tsunami, Ms. Ito said that her regret was that she had been unable to sing that night. "I'd practiced the night before, and after putting my thoughts together, I thought this song would be all right," she said. "It ended without my singing," she said. "It's such a nice song, too."