Tomb Raider

|

|

|

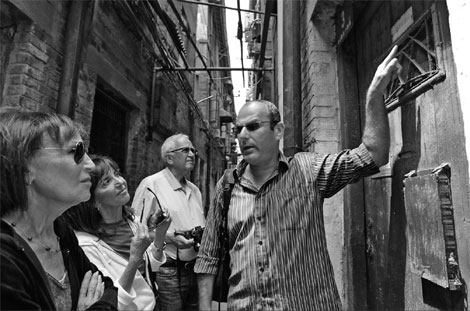

Shanghai tour guide Dvir Bar-Gal is an expert on the city's Jewish refugees during World War II.[Photo/China Daily] |

Israeli tour guide leaves no gravestone unturned in bid to save Shanghai's Jewish history. Matt Hodges reports.

In a dank apartment in Shanghai's most famous ghetto, which 70 years ago housed at least 20,000 Jewish refugees, a huddle of tourists ?mostly Jewish-American retirees ?are watching a TV screening of an excavator hauling a gravestone out of a mudflat.

One of the guests, 79-year-old Bill Feldman, is struggling to stay awake in the baking summer heat. He nods off, jolts awake, and then wonders aloud if a man he met in Los Angeles, a Jewish boxer who spent two years walking from Eastern Europe to Shanghai, ever walked through this community.

Back on TV, several trucks are shuttling a collection of tombstones from one storage depot to another.

Meanwhile, the documentary maker, Dvir Bar-Gal, who also happens to be the tour guide, asks onscreen if the displaced burial stones will ever find a permanent home.

For him, the story of Shanghai offering refuge from Nazi persecution when most countries looked the other way is not yet finished. Local media came up with a nickname for him years ago: Tomb Raider.

This trip down memory lane, private or collective, motivates many Jewish travelers (and non-Jewish expats) to sign up for Bar-Gal's five-hour guided tours of the city, once dubbed "The Port of Last Resort".

The Israeli reporter-cum-historian starts his tours at the opulent Bund riverside, and specifically at the Peace Hotel, an art-deco masterpiece built by Sephardic Jew Victor Sassoon in 1920.

He then moves on to Huoshan Road, or "Little Vienna", past China's first British-made prison and through the 2.6-square-kilometer ghetto in Hongkou district that housed the Jewish refugees - China puts the official count at 30,000 - during World War II. About 70 percent arrived between 1939 and 1941.

"We go from the very haves to the very have-nots," Bar-Gal says.

Lining the river's west bank are relics of Shanghai's golden period in the 1920s and 1930s, when it served as the financial capital of the Far East.

Several of the buildings, as well as much of the property on Nanjing West Road - Shanghai's Park Avenue - was once owned by Jewish entrepreneurs, we are told. Bar-Gal breaks the Jewish migration into Shanghai into three digestible chunks: the Baghdadi Jews, the Russian Jews and those who fled Hitler's concentration camps.

Many of the visitors are aware of the last group, which includes former US treasury secretary W Michael Blumenthal and Far Eastern Economic Review cofounder Eric Halpern. Other Jewish luminaries include Eli Kadoorie, the poor clerk who built the legendary Peninsula Hong Kong, and Silas Hardoon, the Sassoons' rent collector who went on to become "the real-estate king of Shanghai".

They are less familiar with early 20th-century figures, such as adventurer Morris Cohen, who served as aide-de-camp to Sun Yat-sen, founder of the Republic of China.

As the group heads northeast in white minivans, some are surprised to find the ghetto has not changed much in the past seven decades: It is still cramped, dirty and increasingly out of place with Shanghai's glitz.

Bar-Gal says that by the war's end, all but 3,000 of the Jews had left, mostly for the United States or Australia.

As of 1976, only 10 Jews remained in the city, according to local media. Bar-Gal says the expat community has since picked up, from 300 in 2001, when he arrived, to 3,000.

As for the ghetto where the Japanese controllers of the city shunted the Jews in May 1943 at the request of their German allies, much of it seems stuck in a time warp.

The checkpoints are long gone (the compound was never walled off), but the lanes remain narrow enough at points that neighbors can still pass salt from one upper-story window to another with ease. Anti-Semitism from the Japanese was rare.

"Generally speaking, there was no discrimination against the Jews by the Japanese, but what you see is a subtle change of attitude as the Germans flexed their muscles," Bar-Gal says.

"The Japanese told them they were controlling them to keep them safe, so you never really know."

As at other points of the tour, Bar-Gal whips out his iPad to introduce some of the heroes of the time.

The list includes Ho Feng Shan, the Chinese consul-general in Vienna who saved thousands of lives, and Japan's Chiune Sugihara, the diplomat who helped thousands of Jews escape Poland and Lithuania.

"Dr Ho is probably the most important Chinese gentile," Bar-Gal says, adding that he lobbied for the Shanghai Jewish Refugees Museum to be named after Ho.

What is just as interesting is the conundrum facing the current authorities as they struggle to deal with this sensitive slice of history.

It occurred just before the Communist Party of China came to power and nationalized property - some of which the Jews, most of whom came from bourgeois backgrounds, had recently purchased.

"About eight years ago, we thought we were going to lose whole rows of housing here," Bar-Gal says, discussing government plans to raze parts of the ghetto.

"Now, they seem more interested in preserving it."

Apart from building the refugees museum at the site of the old Ohel Moshe Synagogue, authorities are apparently willing to rent the area out to developers - with the caveat that they cannot redevelop it.

"If you've got $700 million, I know the number of the man you should call," Bar-Gal quips.

"Funnily enough, there haven't been many takers so far."

Not that life in the ghetto was easy. Some 2,000 Jews died, mostly from malnourishment or disease; 366 couples married, including 10 to 15 mixed marriages, and 104 divorced.

Bar-Gal has been collecting Jewish gravestones and plans to build a memorial site but has yet to win approval from the city.

"When I came here, not even one Jewish grave had been left intact where it used to stand," he says.

With Schindler's List co-producer Branko Lustig planning a Hollywood movie about wartime Shanghai later this year, public pressure to give the graves a home may mount.

Tentatively titled The Melanie Violin, the film about an unlikely romance between a Jewish musician and a Chinese woman will be a Chinese-US co-production based on a novel by Chinese-American He Ning.

But for the moment, the memories of those who experienced the ghetto, or people like Allan Morrison, who are somehow connected to its past, keep it emotionally charged.

Halfway through the tour, in a tiny park that bears a plaque memorializing the "Stateless Refugees" - a euphemism for Jews fleeing Nazi persecution - Morrison leafs through a dog-eared copy of the Emigranten Addressbuch (Immigration Address Book) when he suddenly breaks into a smile.

"There he is. Adolf Sonnenfeld: 765 Tongshan Road," the 75-year-old Californian physician says, pointing to a name on some brittle yellow paper.

The tour book lists former Jewish residents of the Shanghai ghetto.

"That's my friend. He was brought here when he was about 4. He remembers the ghetto," Morrison continues.

"He lived it. He was only allowed to stay there. He said it was very crowded, but he felt safe. He felt that at least they were respected."

Bar-Gal replies: "We're going to end our tour at 821 Tongshan Road."

|

|

|

Bar-Gal uses his iPad to introduce some of the heroes who helped Jews during World War II to his guests at Shanghai's Bund. [Photo/China Daily] |